The north-south precipitation dipole in CA persists, though with some recent attenuation

The last couple of weeks have featured a mix of wet and dry weather statewide–not uncommon for February and March in California. More unusual has been the periods of considerable warmth–in some cases, record-breaking–across parts of the state in recent days. But overall, the last couple of weeks have been a less dramatic period (meteorologically speaking, at least) than January and early February were.

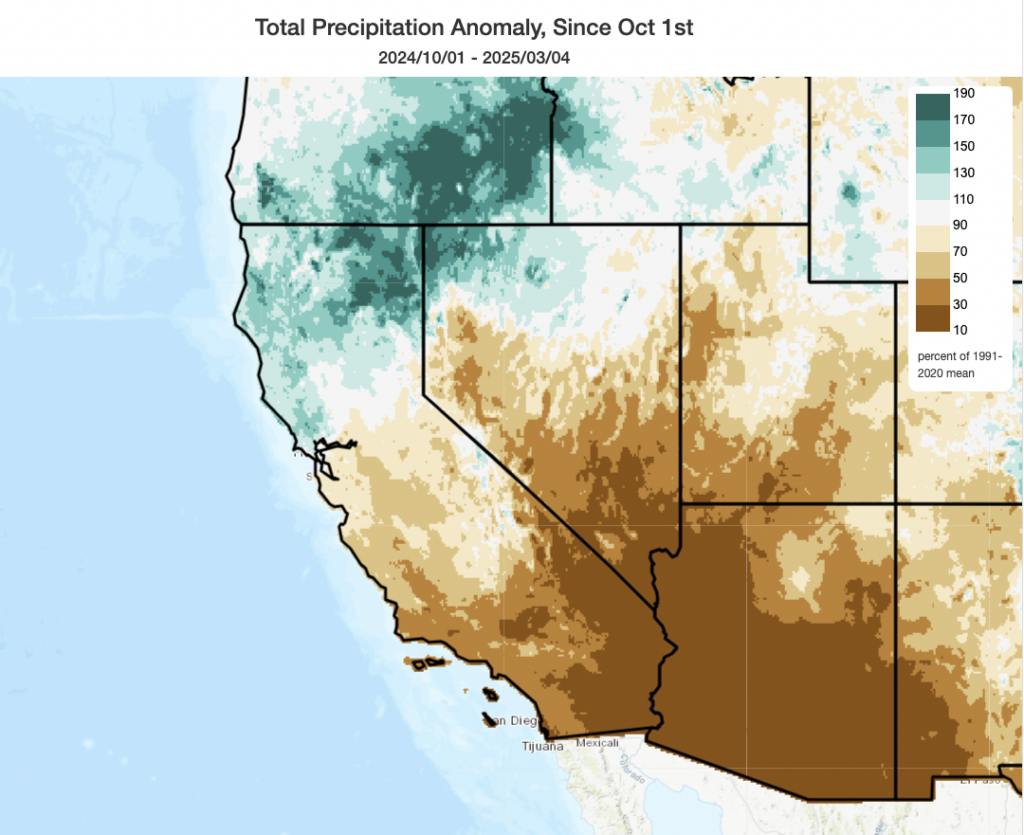

What about the pronounced wet north/dry south “precipitation dipole” that has persisted for some months across California? Well, is still there, and still pretty notable–though less so than in months past. Nearly all of SoCal, including the entire coastal swath from Santa Barbara County south to San Diego County, is still running under 50% of average for season-to-date precipitation while nearly all of CA north of about the Interstate 80 corridor continues be wetter than average for the season to date (with some pockets of NE CA running ~200% of typical numbers!).

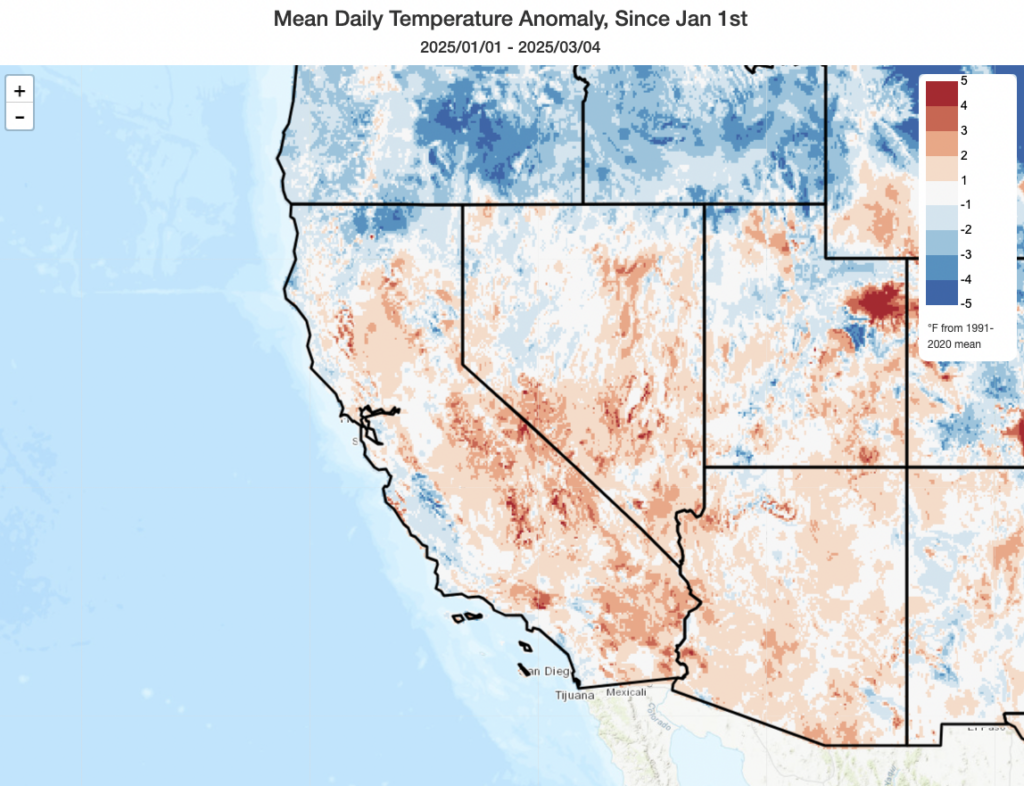

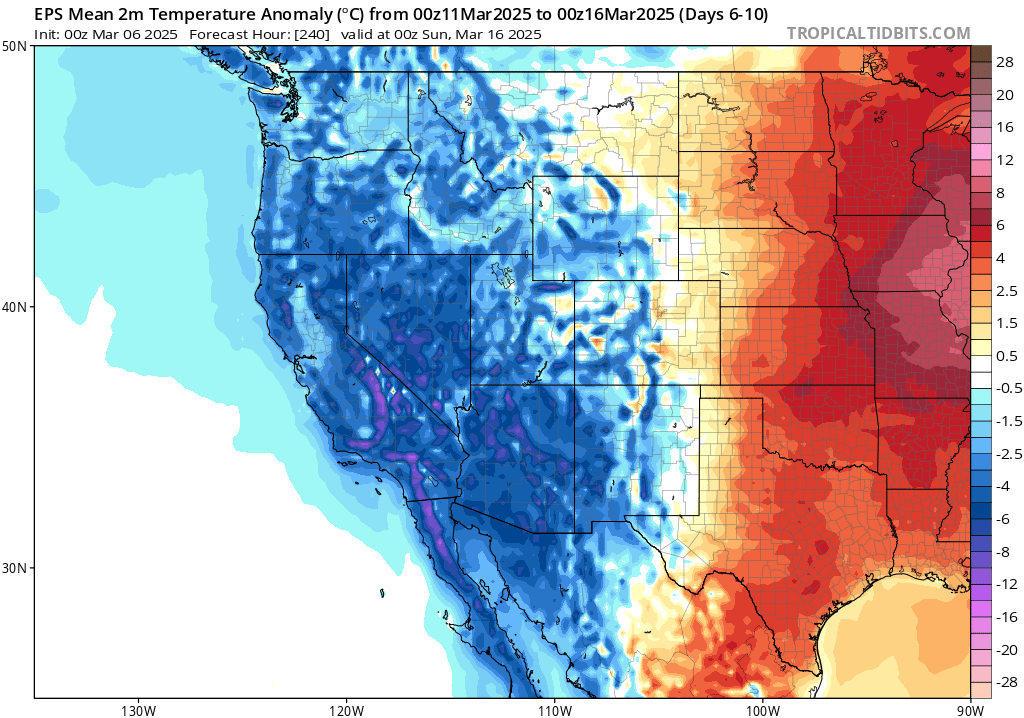

Despite these episodes of anomalous winter warmth, since January 1 temperatures have overall been reasonably close to the recent multi-decade winter average (though it’s always worth noting that these recent average values are much warmer than their 20th century counterparts–an illustration of “shifting baseline syndrome” in action!). Notably, the central and southern Sierra have been several degrees warmer relative to even this elevated recent baseline, so this partially explains why snowpack in the southern 2/3 of the mountain chain is below average at the moment.

A relatively active pattern will continue through mid-March, with potential for solid SoCal soaking (though uncertainty persists)

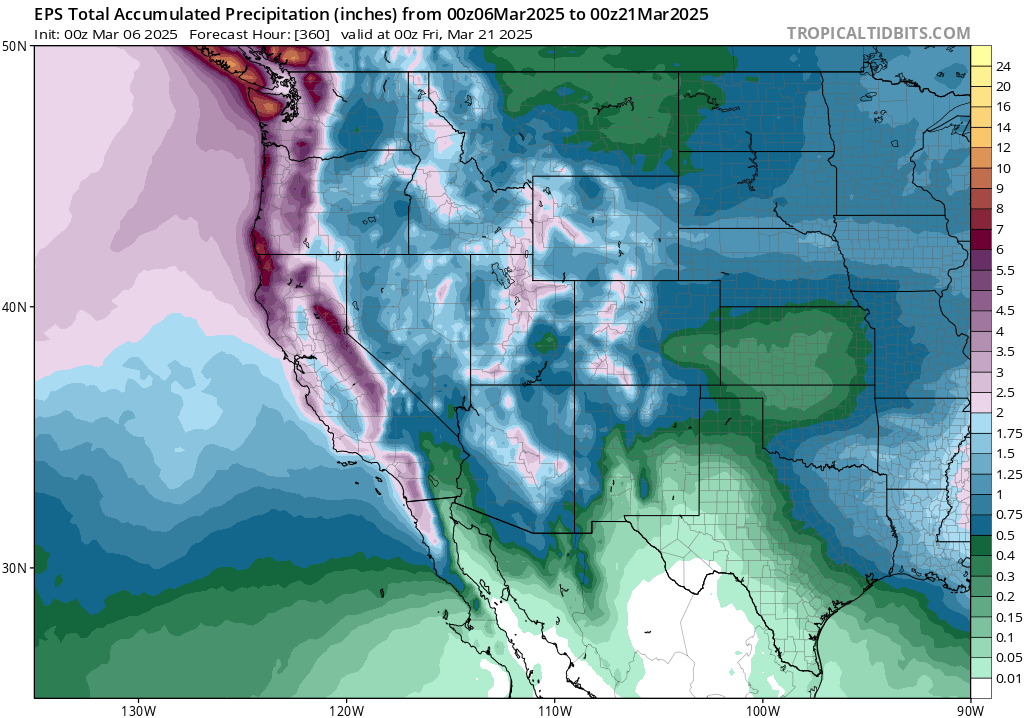

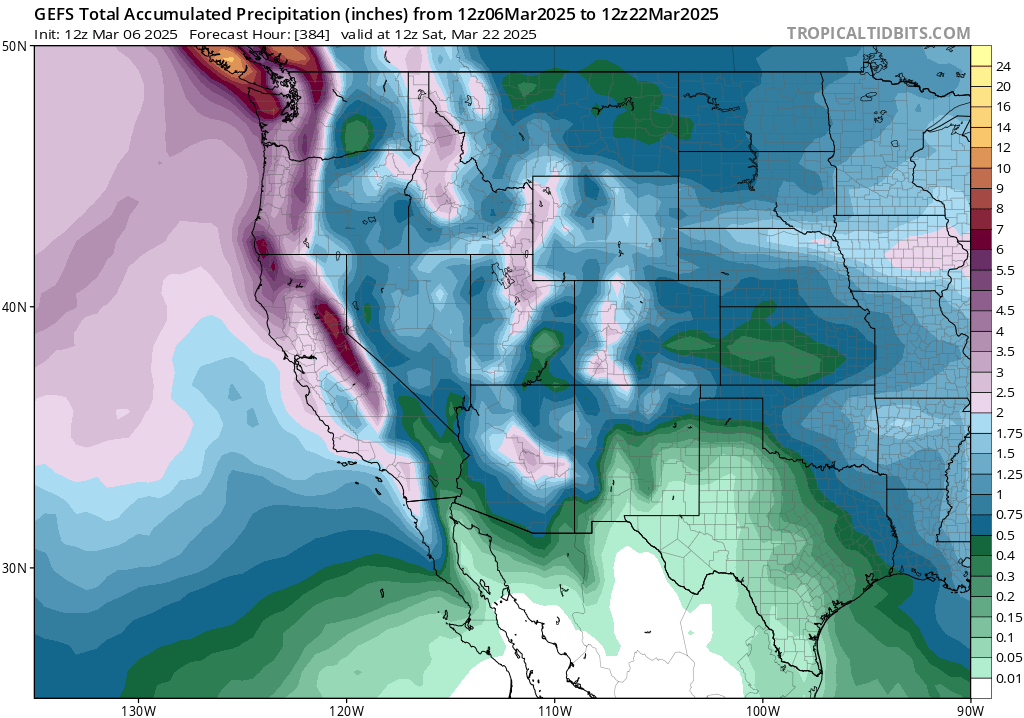

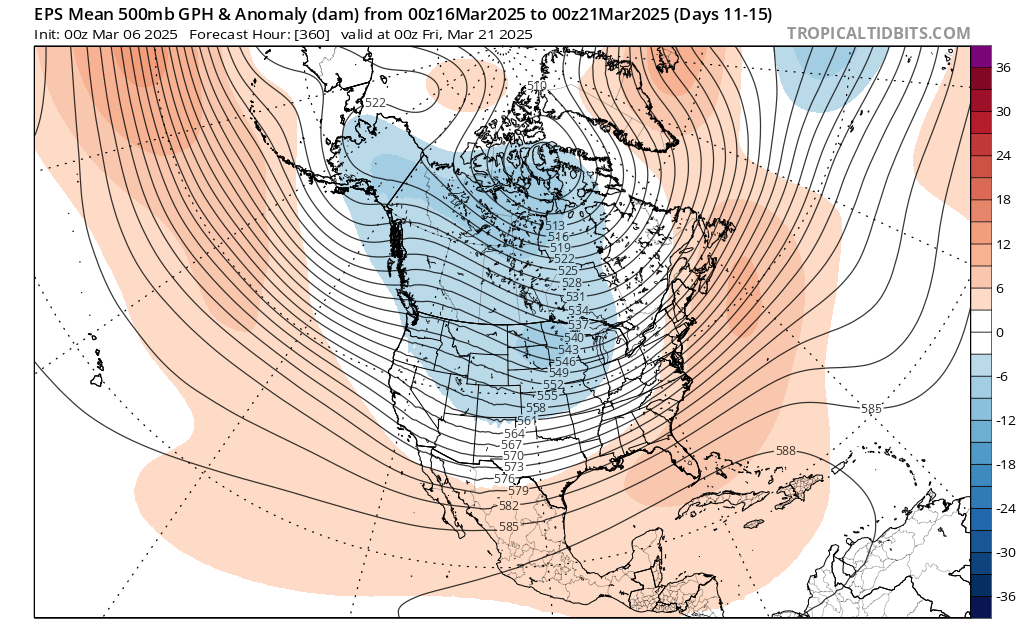

The next 10 days or so will feature what is known as a “progressive” pattern across the northeastern Pacific. This means that there will be an alternating sequences of troughs and brief/transient ridges in between, with an overall active/unsettled pattern. In many ways, this is quite a beneficial winter precipitation-generating pattern as there will likely be notable breaks between storms (reducing flood risk) but each individual storm could bring fairly substantial rain and mountain snow (bolstering water supply/snowpack). At the moment, it looks like the precipitation from this upcoming active period should be pretty widespread and well-distributed statewide, with SoCal likely to see 2 separate events with at least widespread moderate (locally heavy) rain during this period.

There is a bit of uncertainty regarding the southern extent of the heavier rainfall during this period–the ECMWF ensemble is notably wetter than the GFS ensemble at the moment across SoCal, though both ensembles bring widespread substantial rainfall to the entire CA coastal region during this period. For the moment, none of these systems appears individually all that concerning from a hazards perspective, and I also think they will be probably be spaced out enough to prevent significant flooding. There could be a localized risk of debris flows in the recent SoCal burn areas at times, as did indeed occur following the early Feb event, but those details will become clearer as the storms approach.

There may also be, at times, an unstable atmosphere associated with one or more of these upcoming systems–enough to generate isolated to scattered thunderstorms (mainly along coast and in Central Valley). We’re getting into the time of year when these types of colder systems can bring heavy small hail accumulations locally down to sea level in such localized convective cells, or perhaps an isolated severe thunderstorm/mini-supercell or two if local surface wind convergence and jet-level winds cooperate. It’s too early still to discern those details, either, but…’tis the season.

Finally, these storms look like they will be excellent snow producers for the Sierra at least, so I would expect snowpack numbers to look comparatively better (especially in the southern Sierra) 10 days from now. Some stronger and gusty winds will also be likely at times, particularly across NorCal, associated with various cold frontal passages.

As La Niña fades, some thoughts on spring and (early) summer

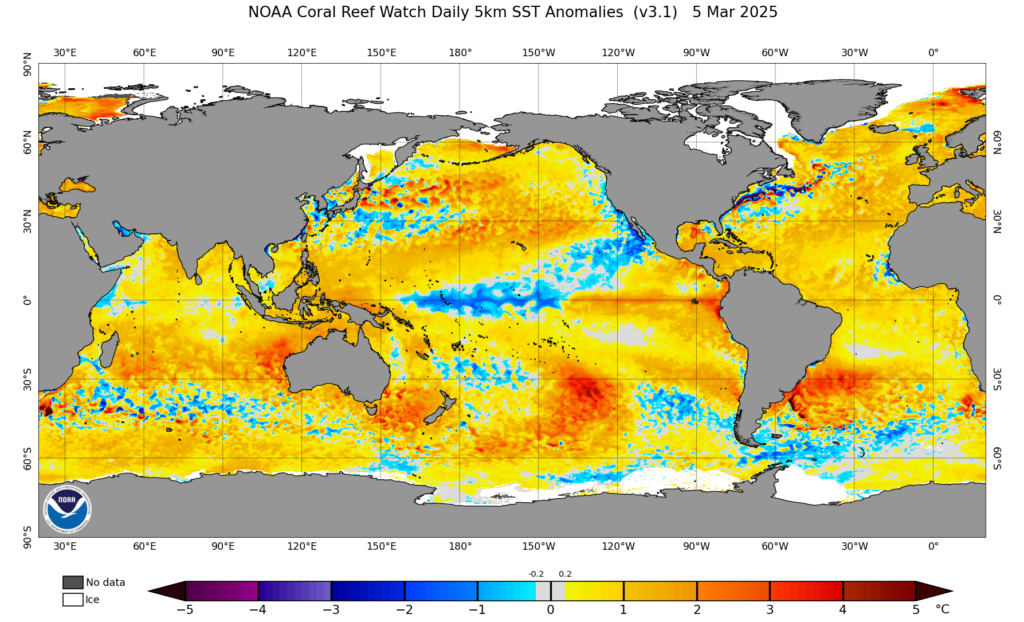

There have been some rather dramatic developments in the eastern tropical Pacific in recent days, with the sudden emergence of much warmer than average temperatures especially along the immediate coast of South America (i.e., west of Peru). This coastally-focused anomalous warmth has come to be termed an “El Niño Costero” (coastal El Niño; or ENC) to differentiate it from a more zonally elongated typical event. ENC events can have large implications for marine life near and east of the Galapagos and also for weather in Peru, often bringing much warmer and wetter conditions than usual to the coastal region there. But ENC effects beyond the immediate region of warmth are much less pronounced than during full-basin EN events, so its broader relevance is not likely to be large at the moment.

Meanwhile, unusually cool temperatures persist in the central tropical Pacific–the remnant of what could be considered a moderate to strong “relative La Niña” event using metrics that account for the non-uniforming warming trend in the Pacific Ocean. That substantial La Niña event, which has likely played at least a partial role in the SoCal/Southwest dryness so far this winter, has still largely retained its influence into March and still appears to be affecting the broader atmosphere for now. But all indications are that this lingering La Niña will continue to fade this spring as ENC persists in the east, with a progressively weakening influence moving forward on conditions in California. In fact, by summer, ENSO neutral conditions will likely exist in the Pacific, and we’re still on the wrong side of the Spring Predictability Barrier to know what lies beyond that.

One other interesting thing to note, regarding the ocean surface temperature (SST) anomaly map below, is both the continued widespread global ocean warmth (virtually everywhere but the central tropical Pacific and a swath extending from there to Baja CA) as well as the streak of highly anomalous warm water extending from southwest of Hawaii nearly to the CA coast in the subtropical North Pacific. This swath represents the “Pineapple Express” (PE) atmospheric river corridor, and is indicative of the potential for any substantial PE-flavored ARs that form the rest of the season to pick up some extra moisture (and be a degree or two warmer) than they would be otherwise.

The latest seasonal models have yet updated for their March cycle, but latest indications continue to suggest that a drier-than-average spring and early summer is still favored across SoCal and the lower Colorado River Basin. Warmer than average conditions will be much more widespread across the West, and April-June could feature some substantial early season heatwaves across some parts of the West if the projected anomalous interior ridging pattern comes to fruition. Upcoming rain and snow through mid-March will help temporarily offset these effects partially in SoCal, but in general I am still anticipating an earlier and more intense start to the wildfire season than usual across the interior Southwest and likely SoCal. Wildfire season emergence will be murkier in NorCal and the PacNW, as conditions have been much wetter up north this winter though this could be partially offset by the quite strong early season heat signal in some of these regions (depending on elevation and ecosystem type). I’ll have more to say about the summer to come as it draws closer, but for now I’d generally expect the spring to look similar to the winter so far (unusually dry in the south with near to above average precipitation in the north, though perhaps with a less extremely dramatic north-south precipitation dipole, which is comparatively good news!).

Join me live on Friday, Mar 7, at 9am PT to “Stand up for Science”

On Friday, March 7, I’ll host a YouTube livestream timed to coincide with the start of the main “Stand Up For Science 2025” event in Washington, D.C. This is not a formal SUFS event, but I wanted to offer a virtual option for those who are interested. In the hour, I’ll offer further thoughts on the critical importance of weather and climate science in our day-to-day lives (yes, even those of us not glued to a weather blog!), how weather and climate science function in the United States and globally and how recent and further expected changes at the federal level in the U.S. are profoundly disrupting them. I’ll also offer some (hopefully!) actionable perspectives regarding emerging career challenges, strategies, and potential opportunities aimed toward current students in the weather/climate field and also federal workers who have recently and unexpectedly lost their jobs in the weather, climate, and wildfire space.