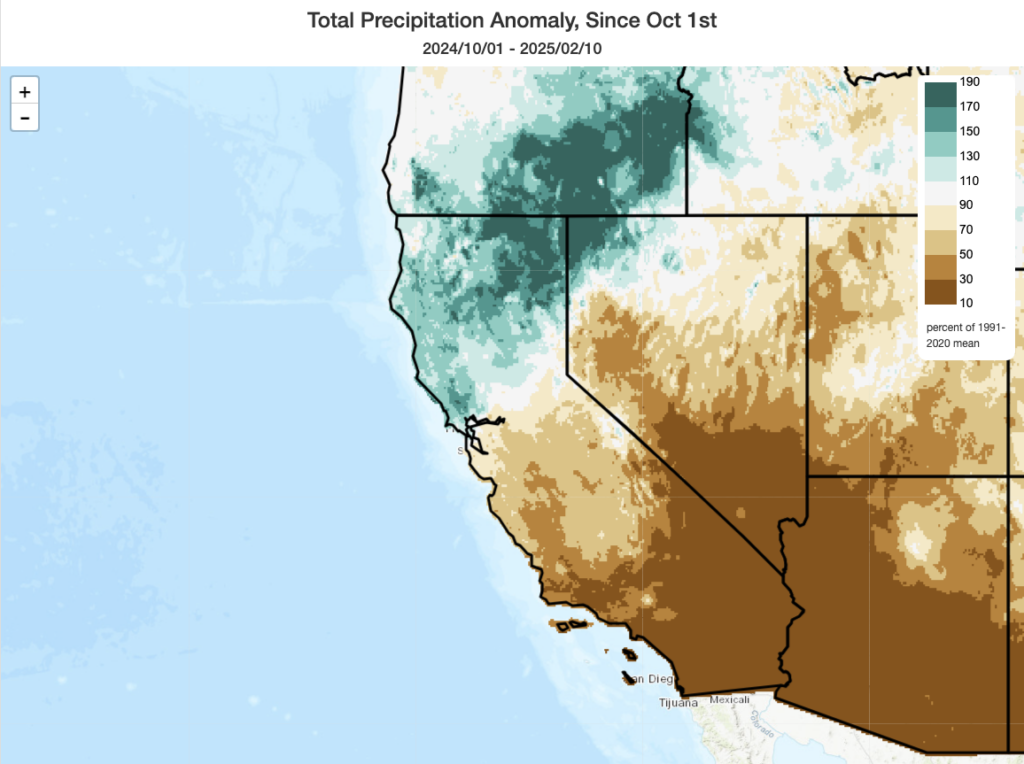

California’s extraordinary precipitation dipole has persisted into mid-Feb with only slight attenuation

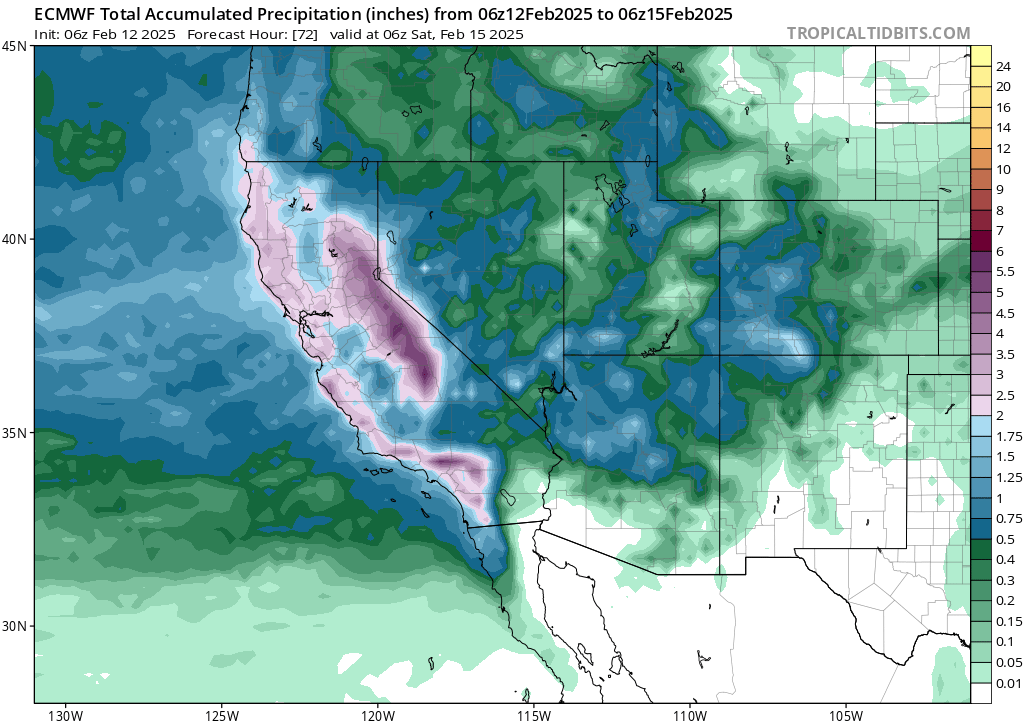

Well, it has finally rained in Southern California this winter. But nearly the entire region remains woefully behind average. And the much-discussed north-south precipitation dipole has persisted all the way through mid-February, with NorCal remaining exceptionally wet (with some locations in the northeast interior of CA (including portions of the Modoc Plateau) experiencing record-wet conditions for the season to date and most regions south of the SF Bay Area below average (with some continued pockets of record/near record dryness in the southern third of the state). This dipole will probably continue, in some form, for the rest of the season–but the upcoming heavy precipitation event preferentially focused on the southern half of the state will mitigate it somewhat and probably bring all areas in SoCal out of “record dry” territory.

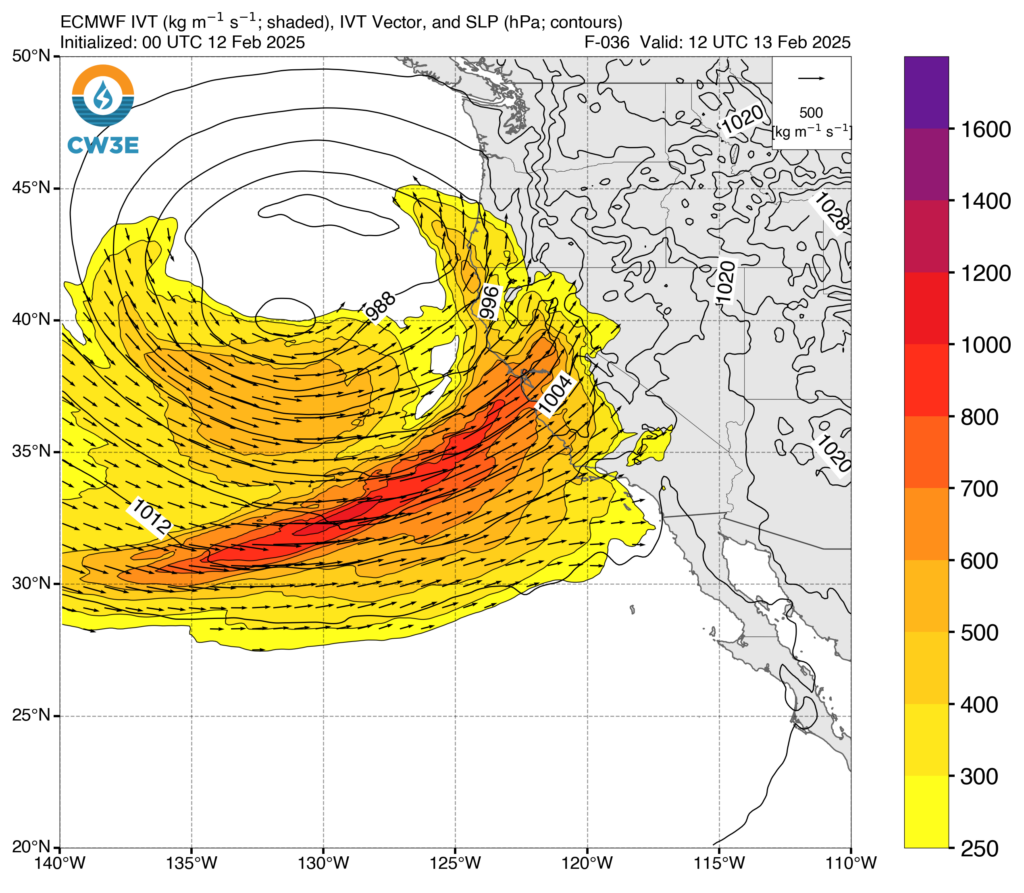

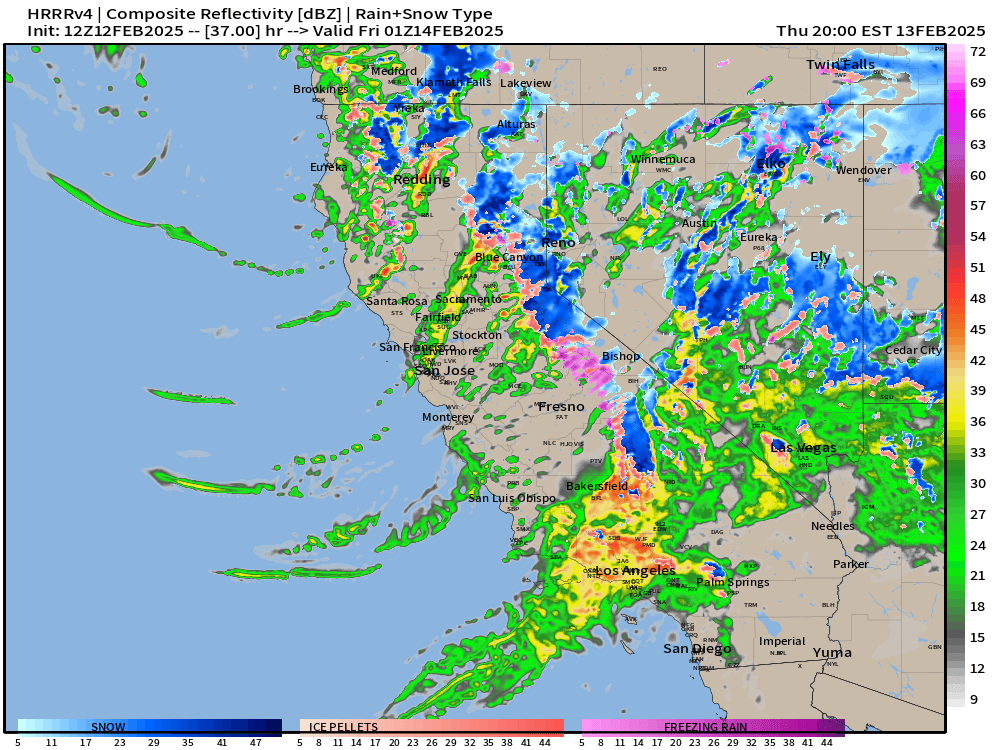

Rapidly deepening surface low plus warm atmospheric river will yield dynamic Thu storm statewide

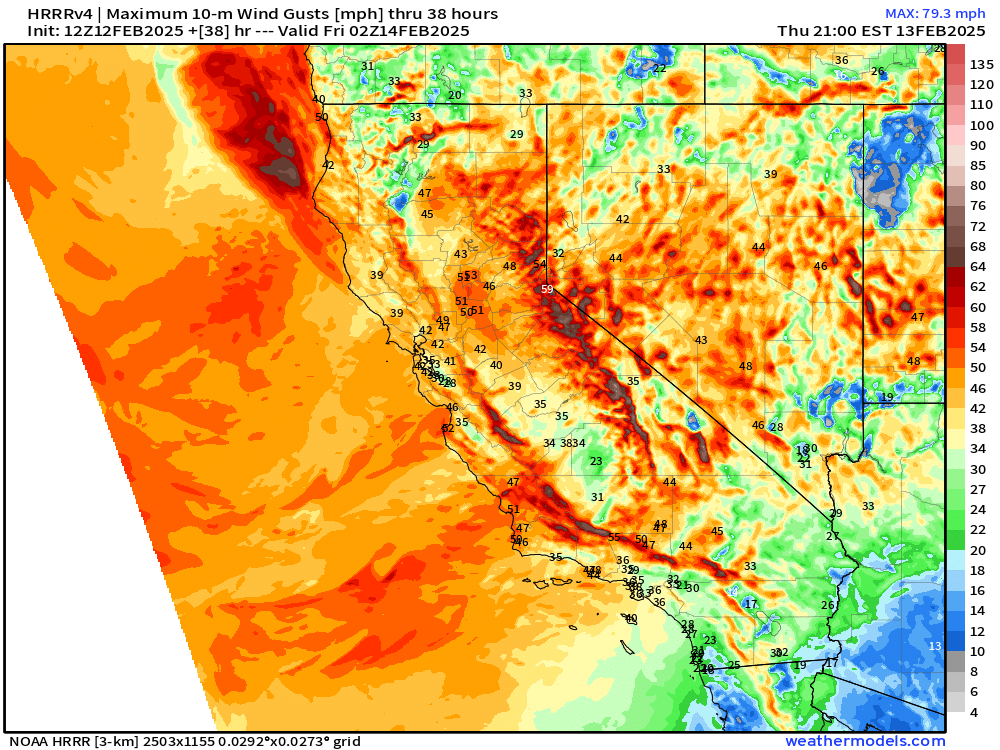

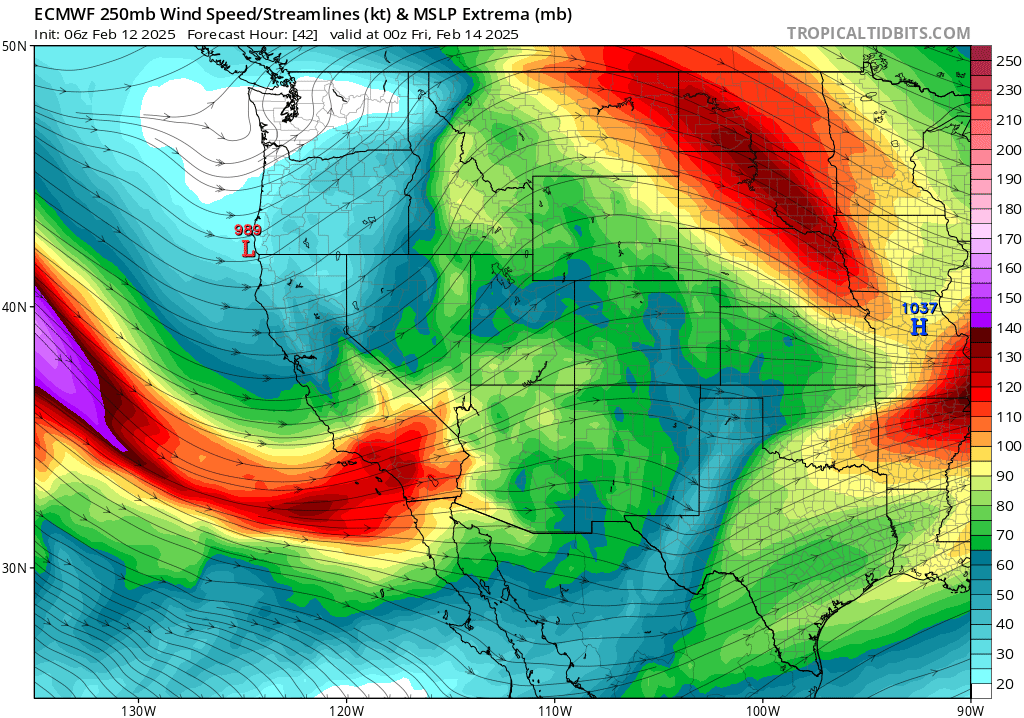

As is often the case with California winter storms featuring more intense rain and wind along the coast, this week’s will feature a rapidly-deepening surface low west of the North Coast and a warm/moist atmospheric river becoming entrained by the storm’s warm sector. In fact, the low pressure system will come close to (but will probably not quite achieve) “bombogenesis” Wed into Thu, based on its projected rate of deepening. Fortunately, the storm won’t have a great deal of time to deepen further and the low pressure center will remain off the coast. But this rapid deepening process overnight, thanks to favorable jet dynamics overhead, will facilitate a strengthening of the cold front as it moves ashore Thu AM in NorCal and a maintenance of that strength as it moves into SoCal Thu PM. In addition to heavy rainfall (discussed more below), strong and gusty winds are likely across much of the state at various points between Thu AM and Fri AM. While winds do not appear likely to become especially extreme or damaging compared to other events in recent years, widespread 40-60 mph gusts are possible–locally higher–and that could still bring down trees/powerlines in some places as soils will be saturated.

This system will exhibit classic, perhaps textbook, structure–with a well-defined and strong cold front preceded by a meaningful warm front. Both of these features will likely be clearly apparent on satellite imagery tomorrow, and may also be noticeable to astute observers on the ground. Not all California storms have such well-defined structure, and that’s often a characteristic associated with more “dramatic” cold frontal passages in this part of the world (in terms of the suddenness of the onset of heavy rain, strong winds, and potentially the occurrence of some isolated lightning as well). Central and southern CA will be in the favorable “left exit” region of a strong jet streak as the atmospheric river moves overhead, which is favorable for enhanced upward vertical motion and thus formation of heavy precipitation (as well as the potential for some isolated thunderstorms).

High risk of SoCal burn area debris flows; lesser though still notable flood risk elsewhere

Southern California desperately needs more rain this season, and the good news is that this system will certainly bring some. The bad news is that it may fall too hard, too fast, to avoid a substantial risk of debris flows and perhaps flash flooding in, near, and downstream of recent wildfire burn areas in SoCal. This includes both the more recent fires in western/central LA County about a month ago, in January, as well as those which occurred during the other major SoCal wildfire outbreak in September (which were most intense/widespread in the mountains of eastern LA and western San Bernardino County). While the whole region should see a good soaking, the SoCal mountains will see widespread 3-6 inch totals (locally higher), and that does include most of the major recent fire footprints.

Unlike deep-seated landslides, debris flows involve a higher ratio of water to solid material and are therefore more “mobile.” They also generally form in primarily response to intense short-duration precipitation (as opposed to other sorts of geologic mass movements, regarding which the overall degree of soil saturation and antecedent precipitation is of greater importance). Debris flows, which are already relatively common in the mountains of Southern CA, are more likely in recent wildfire burn areas for several reasons–including removal of vegetation and soil-anchoring root systems; lack of resistance to surface flow/”sheetwash” due to the creation of a “hydrophobic” surface soil layer where intense fire occurred and the overall smoothing of the land surface due to lack of plant cover; and introduction of loose debris (especially fine ash and soil, but also potentially including larger debris including logs and rocks destabilized on steeper slopes).

There will be two “types” of precipitation during the Thursday storm that could produce debris flow. First, the atmospheric river itself, featuring a very moist airmass being transported by strong winds at lower levels of the atmosphere directly into the “catchers’ mitt” of the Transverse Ranges–which will help, via very efficient orographic lifting, to squeeze out heavy rainfall before the cold front arrives–potentially yielding rainfall rates exceeding a half inch per hour in the mountains (enough for debris flows in some areas). Then, as the cold front arrives (and immediately behind it), convective showers and isolated thunderstorms will likely form due to some slight surface-based atmospheric instability and relatively strong dynamic lifting from the front itself. These embedded convective elements along the front could well produce localized rainfall rates up to (or even exceeding) 1 inch per hour–almost certainly enough to generate debris flows if they occur within recent fire footprints. Downpours of this intensity will not occur everywhere, but this is the portion of the storm that is of most concern from a flash flood and debris flow risk in SoCal. Some flooding (especially urban/roadway type) may occur elsewhere, but the risk of dangerous/damaging debris flows will primarily be in or near the recent fire zones.

In northern and central California, there will also be some risk of flooding from this event (and the NWS has pretty widespread Flood Watches currently out). Up north, the antecedent conditions have been much wetter than in SoCal, so while precipitation may actually be less in the north vs the south with this event, the flood risk will still be elevated because 1) soils are already saturated, and rivers running relatively high, before the storm arrives and 2) the cold front will still be associated with a relatively brief but still quite intense period of very heavy rain, strong wind, and isolated thunderstorms even up in toward the SF Bay Area–and 1-3 hours of heavy rainfall could produce rapid rises on creeks, streams, and even some smaller rivers on Thursday AM as the front moves through. As the NWS SF Bay Area also notes, shallow landslides/mudslides will likely start to occur with this event given the now saturated surface soil profile. The flood and mudslide risk will generally be greatest south of San Francisco, including the SC Mountains and Big Sur Coast, outside of SoCal though there could be some localized flooding elsewhere too. The central and southern Sierra foothills could also see some flood issues, especially during the earlier/warm advection portion of the storm when snow levels will be very high (before crashing later).

This system will be very warm in SoCal, with snow levels well above 8,000 feet for most of the storm, but it will be much colder in NorCal and there should finally be some solid snow accumulations down to and below Lake Tahoe level this time around (and the Sierra peaks could see multiple feet by Friday, with lesser amounts to much lower elevations too). Notably, the far northern Sacramento Valley (at elevations of 500 feet and higher, including the Redding area) could see a brief period of some locally heavy accumulating snowfall in the early hours of this system due to trapped cold air near the surface (a classic setup for such an event, with a cold airmass up north being undercut by a storm system centered well to the south).

Storm-focused livestream Thursday evening

I’ll have another YouTube livestream Thursday evening (5pm PT on 2/13) to discuss this storm and its impacts. I’m trying to time it to coincide with the approximate time of cold frontal passage, and thus heaviest rain and greatest debris flow risk, in Los Angeles County.

Another perspective on “hydroclimate whiplash” and its local (and broader) relevance to wildfire

In the wake of the devastating Southern California wildfire disasters in January, my colleagues and I were invited to write a “rapid response” piece reflecting on the broader context of this event in light of our recent review paper on global hydroclimate whiplash in a warming climate, including implications for global grassland/shrubland ecosystems and wildfire risk in general. That short article was already published, last week, in Global Change Biology and is freely available for everyone to read (no paywall). I also wrote a short thread, posted on social media, summarizing the key points.

Despite some online claims to the contrary, we do indeed find that late (dry) season (6-month SPEI ending in December) moisture variability has increased (by ~25%) in coastal Southern California over the past century and has in fact reached its highest level on record over the past 20 years. This has been concurrent with an overall drying trend across SoCal during the same period–meaning that while the “driest dries” have become considerably more intense over this period, the “wettest wets” have not decreased–widening the range between the two, and thus the magnitude of the swings between wet and dry states. We also find a striking (~36%) increase in extreme wildfire risk conditions during early winter in coastal SoCal since the early 1980s driven primarily by increasing dry/warm conditions in the preceding weeks/months–specifically, during the November-January peak in offshore wind season–which is directly relevant to the increased occurrence of destructive winter fires in SoCal in recent years.

In this perspective, we also emphasize that while climate change does play an important role in the increased occurrence of extreme wildfire conditions and recent fire disasters, some of the most important risk-reducing interventions in the short term are not directly climate-related and can be implemented at local-to-regional scales. These include building codes that ensure construction of fire-resilient structures, more proactive vegetation in/near communities, preventing unwanted fire ignitions under high risk conditions, and improving emergency communication and evacuation planning in high-risk locations (including those outside of the traditional wildland-urban interface).

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.