Event narrative

Droughts historically have a way of sneaking up on California, and the extraordinary 2012-2014 drought has been no exception.

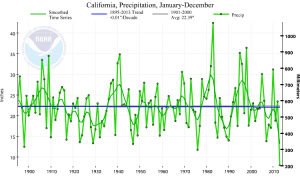

Year-to-year and even season-to-season rainfall variability is quite high in this part of the world, which means that it’s nearly impossible to know whether a single dry year (or season) portends the beginning of a much more prolonged or intense dry period. Indeed–the 2012-2013 rainy season had an extremely wet start–so wet, in fact, that an additional large storm during December 2012 would likely have led to serious and widespread flooding throughout Northern California. But no additional significant storms did occur during December 2012–nor during January 2013…nor February, March, April, or May. In fact, January-June 2013 was the driest start to the calendar year on record for the state of California in at least 118 years of record keeping. Some parts of the state saw virtually no precipitation at all during this period, which made for an especially stark contrast with the extremely wet conditions experienced just a few months earlier.

The role of the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge

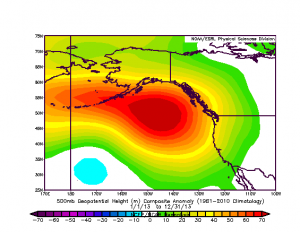

How did this drastic change occur so quickly? The second half of the 2012-2013 Water Year saw the development of the now infamous Ridiculously Resilient Ridge (or RRR)–an extraordinarily persistent region of high pressure over the northeastern Pacific Ocean in the middle atmosphere that forced the mid-latitude storm track well to the north of its typical position and prevented winter storms from reaching California.

While the RRR did become less prominent during the summer months of 2013, it returned with even greater intensity by the fall. In fact, by November 2013, the RRR resulted in such an anomalous high-amplitude flow pattern that much of Alaska–even regions north of the Arctic Circle–experienced record warmth and precipitation, which led to several high impact weather events (including ice storms and enormous avalanches). In California, meanwhile, the precipitation spigot remained tightly closed as Pacific storms rode thousands of miles to the north of where they typically would have been. Most of these winter storms missed even Oregon and Washington, triggering a drought that is now being experienced rather acutely in these regions in the form of massive, nearly uncontrollable wildfires this summer. In California, conditions during January were so warm and dry that wildfires broke out in the far north in the dead of winter–an essentially unprecedented event in this region.

Temporary mid-winter relief

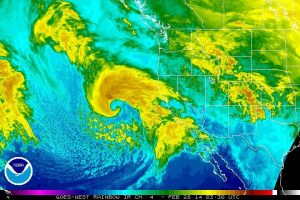

By the beginning of February, the RRR began to lose some of its intensity (and, more importantly, much of its seemingly indomitable persistence). A major pattern change did finally allow a series of significant storm systems to affect much of California, including a fairly impressive atmospheric river event (which affected a relatively narrow region just north of the Bay Area) and a strong winter cyclone (which affected much of Southern California later in the winter).

There were a couple of additional minor precipitation episodes in addition to these, but for the most part, California saw nearly all of its precipitation during Winter 2013-2014 over the course of these two storm systems. So while winter 2013-2014 ultimately came in as “merely” the third driest in the past 118 years, it immediately followed what was (by far) the driest calendar year on record in 2013. And, as it turns out, 2012 was also drier than average on a statewide basis (though not nearly as dry as 2013 or 2014). Thus, the present event now includes 3 successive dry years, and includes the driest year in over 100 years (and perhaps since California’s statehood).

Into the frying pan

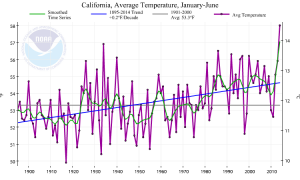

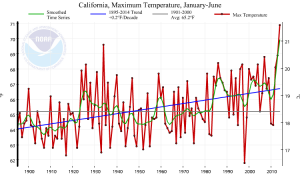

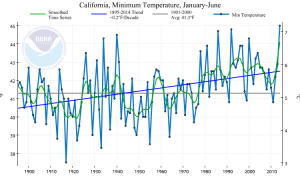

As California’s long-term precipitation deficits have skyrocketed over the past 18-24 months, another dramatic trend has become increasingly apparent: an extraordinary string of record-warm days, months, and multi-month periods. Most notably, California experienced its record warmest winter in 2013-2014, and (as of June 30th) is currently experiencing its warmest year on record to date. Even more remarkable is that these recent temperature record have been broken by a very wide margin–2014 so far has been more than 1 degree warmer than the previous record warmest year. This record-shattering warmth has serious implications for the ongoing extreme drought, since warmer temperatures result in greater evaporation (and evapotranspiration). This means that an even lesser fraction of the already record or near-record low precipitation was actually available to plants and ecosystems–or as rain/snowmelt runoff into California California’s rivers and streams.

Just how severe is the ongoing drought in California?

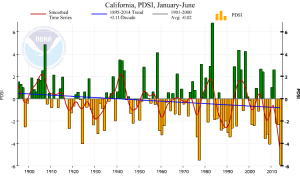

This combination of exceptional dryness and record warmth have acted in combination to produce the most severe drought conditions experienced in California in living memory (and very probably over a century). The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) is an aggregate metric of long-term (meteorological) drought severity–which takes into account observed precipitation, temperature, and soil moisture–and is widely used to characterize the intensity of drought conditions. The PDSI is a normalized metric, with a scale ranging form +6 (wet) to -6 (dry), and any value lower than -4 is considered to correspond to extreme drought. At the present time, a large fraction of California is experiencing literally chart-topping PDSI values less than -6. These values–both regionally and on a statewide average basis–are higher than at any other point since at least 1895, according to the latest NCDC rankings. From these data, it’s entirely reasonable to assert that the present drought is already more intense than any 20th Century drought in California.

Another interesting aspect of the present drought is to note the temporal structure of the large positive temperature anomalies California has been experiencing recently.

One of the most striking features in California’s temperature record is the presence of a distinct long-term trend, on the order of +0.2 degrees per decade since the late 1800s. This trend is present in overall temperature, daily maximum temperature, and daily minimum temperature, but the increase has been largest in daily maximum temperatures, which have increased by over 1.4 degrees F since 1895. Interestingly, the temperature anomalies in 2014 have closely mirrored this overall trend, with all-time records set for both daily minimum and daily maximum values but much larger anomalies occurring with daytime maximum temperatures.

A long-term trend also exists in PDSI values for California, which has trended toward lower values over the past century or so. Interestingly, there have been no statistically significant trends in California mean precipitation over this same interval, which suggests that the strong warming experienced in California is likely responsible for the increasing drought severity. I’ll have a more extensive post on the role of climate change in the current California drought (and the RRR pattern) later this year.

Impacts of the extraordinary 2012-2014 California drought: Where we stand now

All 58 California counties have now been designated by the federal government as primary natural disaster areas due to the drought. A state-level Drought Emergency has been declared, and state authorities have recently taken unprecedented measures to cope with dwindling water supplies. National and international media attention has become increasingly focused on this ongoing extreme climate event in California as economic damages to date surpass $2 billion, and continues to rise rapidly. Increasingly broad swathes of farmland are being fallowed in the Central Valley (especially the San Joaquin Valley), and entities with access to remaining water are auctioning off their rights for over ten times the long-term average rate. Groundwater pumping has increased exponentially over the past 12 months, and there are growing concerns that this virtually unregulated draining of California’s underground aquifers could have major major consequences within the next couple of years.

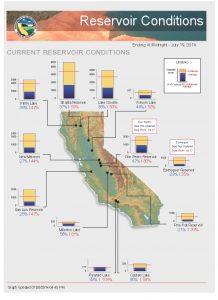

Just how low are California’s reservoirs right now? The figure at right shows that most of California’s major reservoirs are below 50% of capacity, and some are well below that meager level. More importantly, many of these reservoirs are near or below 50% of average capacity to date–which is especially remarkable since water levels are typically well below maximum capacity by this point in the summer. One big problem over the next few months is that the extreme long-term dryness–combined with enhanced human and “natural” demand due to record warmth–will allow reservoir levels to drop at rates greater than the long-term mean.

While last winter’s brief but intense precipitation during February and March prevented California’s reservoir levels from being catastrophically low this summer, many may start approaching record-low levels by October/November 2014. Some small communities in California are at risk of running out of water within the next 3-4 months, but much broader trouble may loom over the next 1-2 years without a series of wet to very wet winters helping to bolster supplies. Even Lake Mead–which is filled by the flows of the Colorado River and is a critical water source for much of Southern California–has dropped to record-low levels as of July 2014 (though it should be noted that these low levels are actually due to a much broader and longer-term drought across the American Southwest).

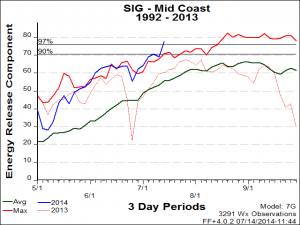

California’s wildfire season has gotten off to a rather ominous start, beginning with the off-season Northern California fires in January, followed by the destructive San Diego-area fires driven by unusually strong Santa Ana winds in May, and has recently continued with unusually intensely-burning fires in Northern and Central California despite the relative lack of extreme weather conditions usually required to sustain such extreme fire behavior.

In fact, several special fuel and fire behavior advisories have recently been issued for much of California due to record-low fuel moistures and potentially explosive wildfire behavior in the coming months. While there has been a relative lull in fire activity across California in recent weeks, current events in Washington and Oregon likely foreshadow a very severe fire season to come in California. Many in the firefighting community are anxiously awaiting the development of extreme fire weather patterns over the next several months–such as dry lightning outbreaks, extreme heat waves, or strong offshore winds–which nearly always occur in California between August and October.

What does the (near) future hold?

The shortest (and, unfortunately, most accurate) answer to this question is: we simply don’t know. The rest of summer will probably continue to be warmer than average, and associated impacts (namely, extreme wildfire conditions and low limited water availability) will continue to grow more acute until that start of the next rainy season during winter 2014-2015. There has been much speculation regarding the likely El Niño event this year and its possible role in alleviating drought conditions in California. I’ve already written extensively on both the development of the present El Niño event specifically and the more general impacts of ENSO upon California precipitation. The quick summary version: connections between California precipitation and El Niño are rather tenuous, except for very strong El Nino events, which are associated with increased cool-season precipitation. This is especially true for inland regions of Northern California, where the majority of California’s reservoirs and “snowpack stored water” capacity resides. While there were some early indications during spring 2013 that the upcoming likely El Niño event could be a very strong event, a top-tier event now appears less likely.

Therefore, while there was never a high chance of El Niño breaking the current California drought, there is now an even smaller of a chance of that happening. We still don’t know how strong El Niño may be, nor how much precipitation California will experience next winter (regardless of what happens with El Niño). There are some indications in the long-range seasonal forecast models that some substantial precipitation may occur during DJF 2014-2015, but such projections are subject to very high uncertainty (especially in light of the uncertain evolution of conditions in the Eastern Pacific). And–as Mike Dettinger has pointed out–it’s quite likely that California’s drought will persist through next year even if we have a relatively wet winter. While a wet (or even near-average) winter would help alleviate some of the most acute short-term effects of the drought, many parts of California have missed out on nearly a full year’s worth of precipitation, and it will take a long time to gain back that deficit even in a best case scenario.

In the meantime, California’s long, dry summer continues. Stay tuned.

© 2014 WEATHER WEST

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.