An increasingly resilient ridge keeps California dry, but with markedly different daily weather in dense tule fog vs non-fog zones, following a very wet and relatively warm autumn

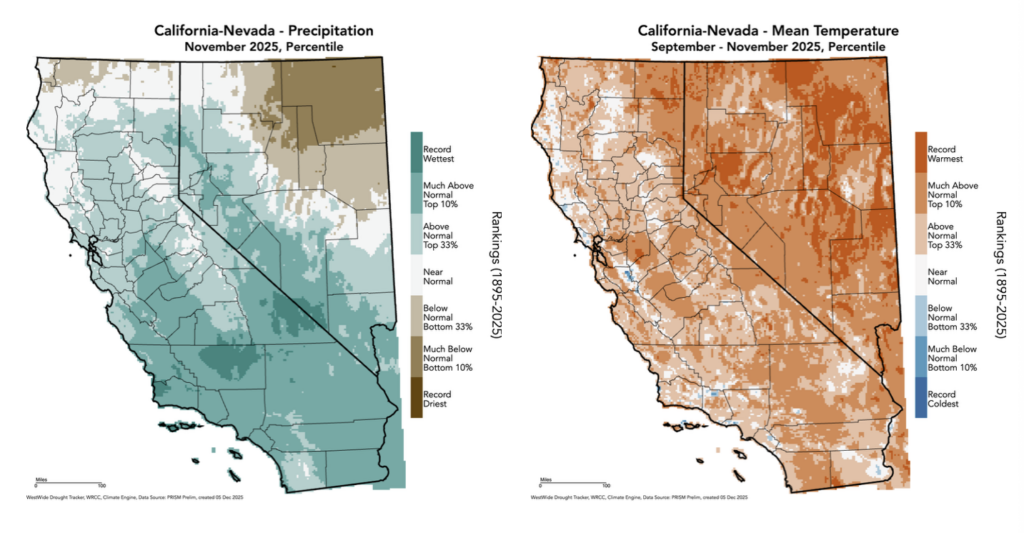

Well, the final numbers are now in and they reflect what everyone has been talking about in Southern California: it genuinely was historically wet this fall in some places, and it was anomalously wet to some degree virtually everywhere south of the Interstate 80 corridor. Sep-Nov 2025 were the wettest on record (going back to at least the late 1800s) in some parts of Central California, including patchy areas in a northeastward-oriented swath from the Central Coast into the San Joaquin Valley and over the Southern Sierra into portions of the Great Basin. Elsewhere in SoCal, most spots experienced a top 10% wettest autumn (and more than a few places saw their wettest Sep-Nov period in decades).

Notably, it was not an especially cool or cold period: in fact, even relative to the recent climate-changed baseline, temperatures in autumn were broadly warmer than average across California and even more so elsewhere across the interior West (where some parts of Nevada and adjacent states saw a record-warm fall). So for much of California, autumn 2025 turned out to be an exceptionally wet yet mild to warm period. The precipitation was something that, clearly, was unforeseen in seasonal outlooks; without a much more comprehensive assessment, I don’t immediately have a good narrative for the proximal cause (though it’s also likely that the broad swath of near to record-warm ocean temperatures over the entire Pacific storm track region upstream of California played a role in “juicing up” the storms that did arrive.

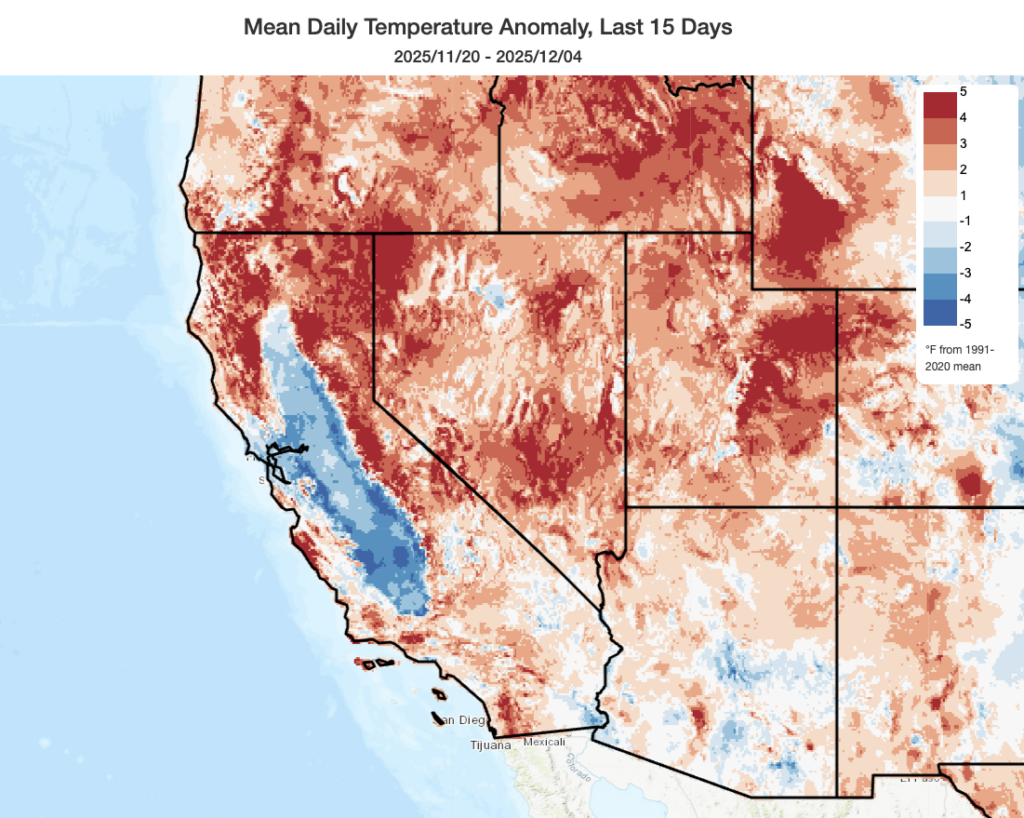

Over the past two weeks, however, the pattern has transitioned to a much quieter and generally warmer one as persistent ridging strengthened aloft. One major exception to that “dry and warm” rule, however, has been the entire Central Valley and occasionally parts of the adjacent SF Bay Area due to the development of highly persistent radiation fog known locally as “tule fog.” This fog has been denser and more widespread on some days than others, but has generally been widespread and lasted most or all of the day in at least some portions of the Valley for the better part of two weeks. This prolonged tule fog episode hearkens back to decades past, when such events were notably more common and prolonged. I discussed the recent tule fog episode, as well as offering some broader fog-related science and historical context, in a recent YouTube virtual office hour.

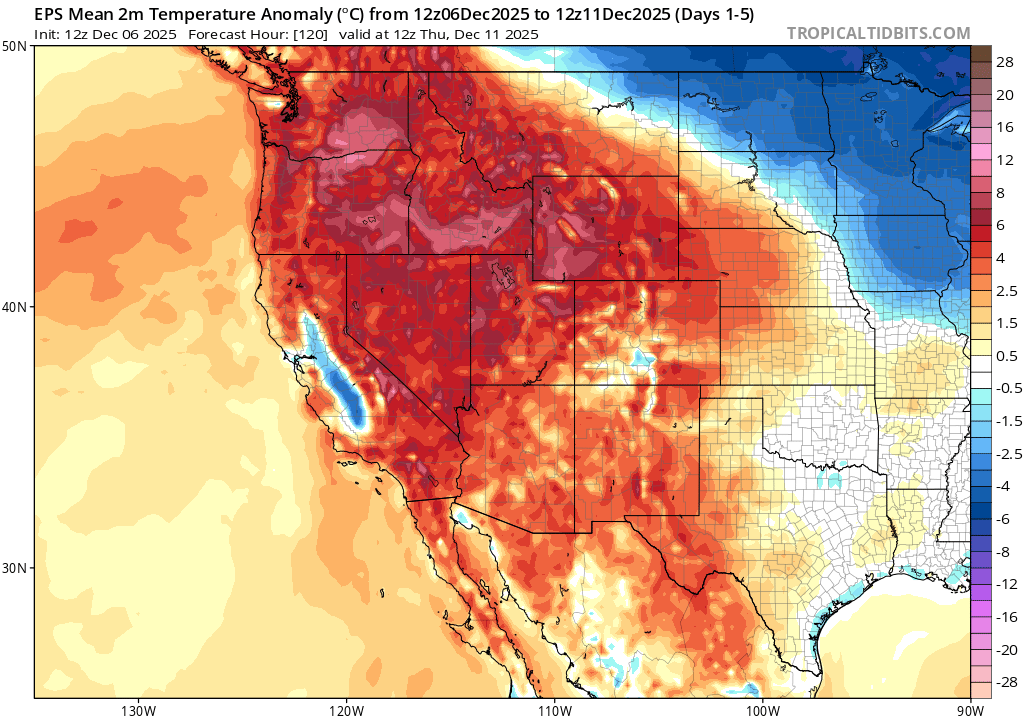

The overall stable pattern allowing this fog layer to persist, however, has actually brought an anomalously warm and dry airmass to the broader West and even most of California outside the fog layer. In fact, there has been a remarkable contrast between well below average temperatures under the fog layer in the Valley and well above average temperatures just a couple thousand feet higher in elevation in the nearby hills and mountains. It has also been warm in SoCal, for the most part, during this period.

It is also worth noting that the present “Central Valley inversion” event has differed from more traditional/historical tule events in that there have been many days on which the “fog” is actually more like a low stratus layer, with ceilings a few hundred feet above ground level and the top of the cloud layer extending 1,000-2,000 feet upward vertically. This could be considered more of a “tule stratus” as opposed to a true “tule fog” event on those dates and in those locations, although there have also been periods of much denser surface fog during this interval as well. Why has this transpired? Well, it might have to do with the fact that the ambient airmass is not at all cold (it is, after all, much warmer than average aloft)–and that there is both a large mass of unusually warm ocean water offshore, as well as a near-complete lack of snowpack in the central and northern Sierra Nevada (leading to a dearth of cold air drainage into the Valley). That all means that relatively warmer surface temperatures (they are still very chilly under the fog, but in relative terms!) have not been quite able to cool to the local dewpoint much of the time, and with an slightly elevated inversion the fog is “lifting” into dense stratus. Might this be a signature of “tule” events in a warming climate? I’m not aware of any research on that topic, but the general trend toward warmer oceans, warmer airmasses, and decreased early-season Sierra snowpack is certainly interesting in that regard.

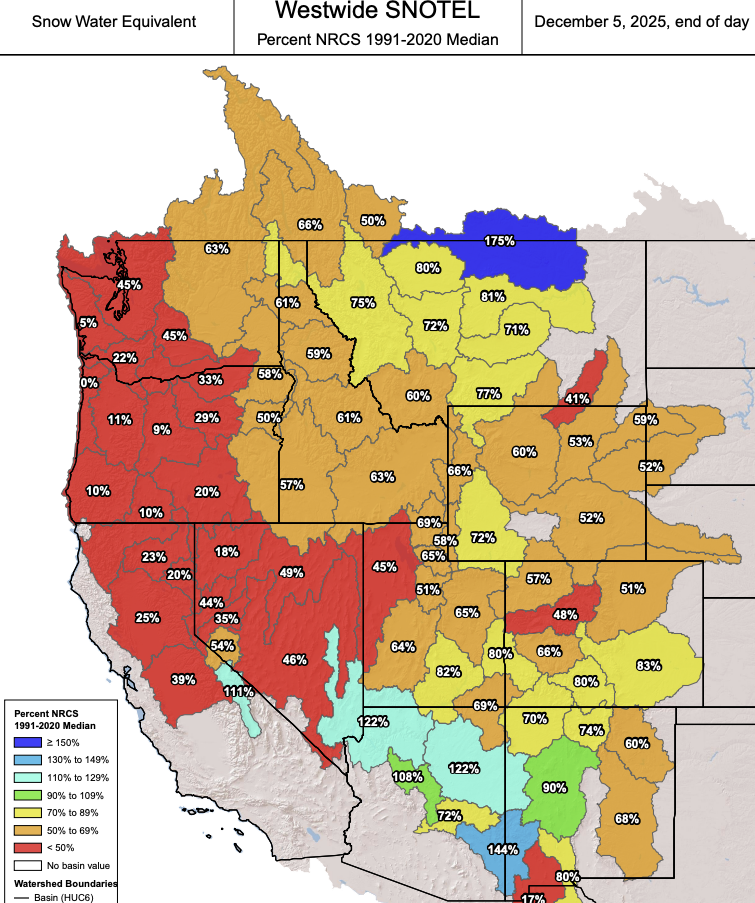

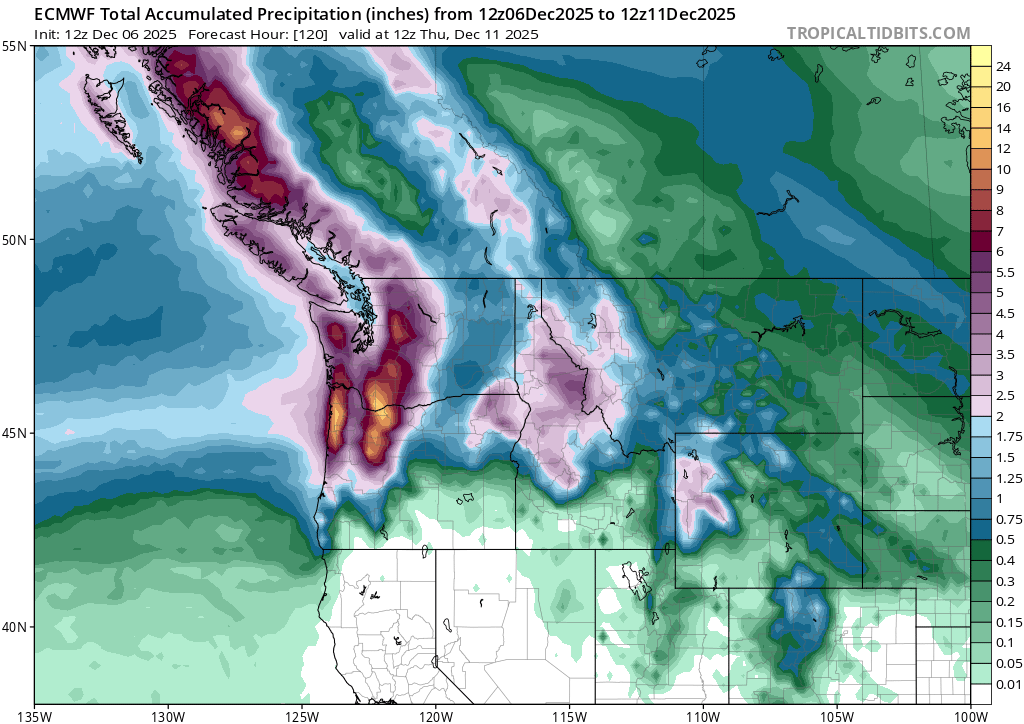

Relative warmth during autumn, as well as continuing warm and dry conditions in many areas at present, has led to notable early-season “snow drought” conditions across nearly the entire West (except for some basins along the Mongollon Rim in Arizona that benefited from the autumn deluge). That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s bone dry out there; there still has been some significant precipitation in the form of rain (or snow that immediately melted) in most mountain locations. And the season is young; recovery from early season snow deficits is not uncommon. But it is notable that this mainly temperature-driven dearth of snowpack across the West is expected to continue for the foreseeable future even as the Pacific Northwest is deluged by flooding rainfall (because the storms will be very warm, with freezing lines generally near or above mountain peaks).

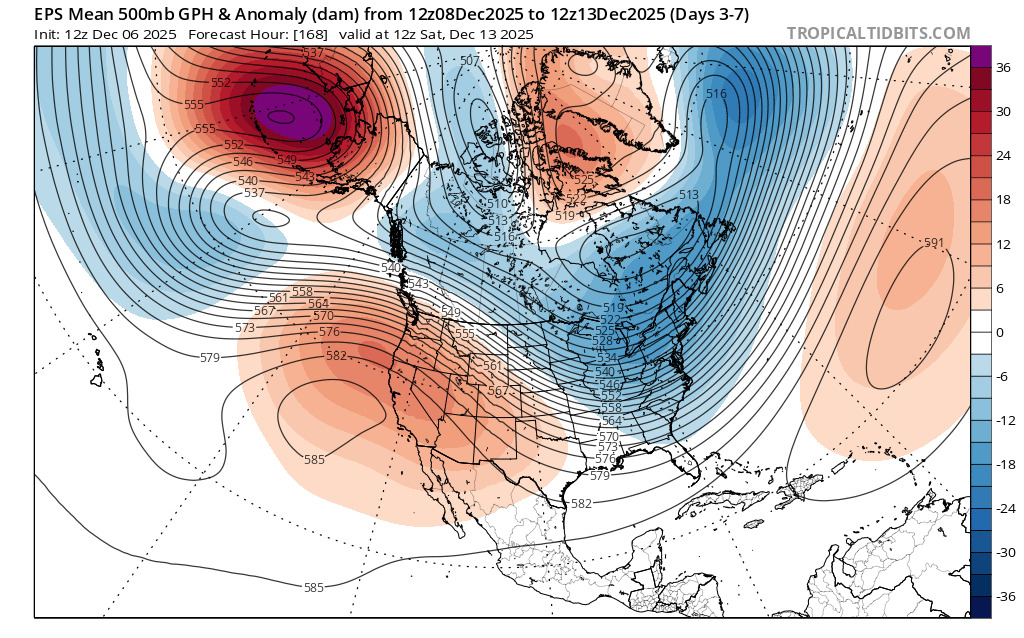

East Pacific/Western ridge will continue for at least another 1-2 weeks; very warm/moist atmospheric river sequence to bring significant PacNW flood risk while CA stays dry

Depending on where you live, and possibly also depending on your personal philosophy regarding fog and/or rain/snow, I’ve got either very good or very bad news for you: The next week is quite likely to look a lot like the last 2 in California, with persistent ridging leading to very warm temperatures and sunny skies in the hills and mountains above the inversion layer (as well as in SoCal), but cold and damp conditions in the Central Valley (and again in portions of the SF Bay Area) as the tule fog layer persists. This is a stagnant pattern, and it won’t change much for at least 7-10 days to come.

The Pacific Northwest, for its part, will see a potentially significant and fairly widespread flood event this coming week as a sequence of strong atmospheric rivers round the northern flank of the ridge and bring very wet/warm conditions. Everything from small creek to mainstem river flooding is possible, and it could be significant in some locations. Part of the problem will be the ambient warmth of this very moist subtropical airmass: in addition to widespread heavy rainfall in the lowlands, snow levels will be so high that close to 100% of the precipitation will fall as rain (vs snow) even in the mountains, increasing the immediate runoff volume.

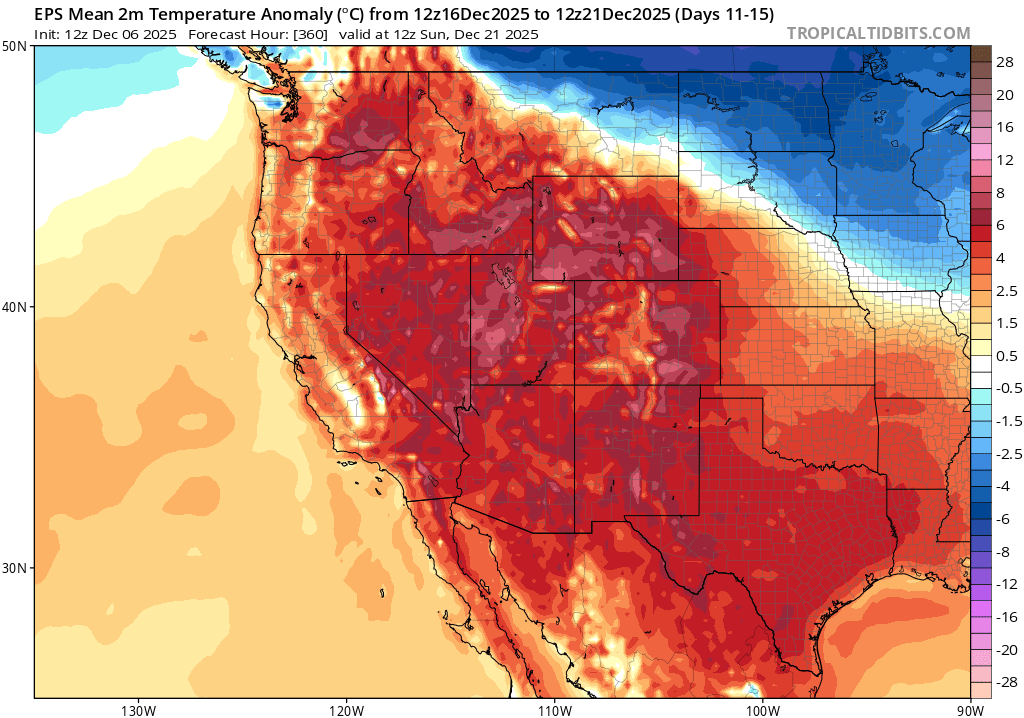

As we get toward mid-late Dec., there is some more uncertainty in the North Pacific flow pattern. On average, the ensembles do depict continued ridging over California during this period, with an elevated chance of dry conditions at least in southern and central California. There is a somewhat better chance that some precipitation could sneak through during this period, especially in NorCal, but that’s far from a slam dunk. One very striking thing about the mid-late December period in the ensembles is the very high confidence in very anomalously warm conditions across nearly the entire West, including much of California, and even including areas that see significant precipitation during this period. That means two things of note for California. First, it means that meaningful Sierra snowpack accumulation will be very unlikely over the next 2+ weeks (even if precip begins to return toward the end of the period). Second, it means that the Central Valley may slowly begin to see reduced fog coverage as the overall ambient dry and warm airmass slowly removes moisture from the boundary layer. Exactly how long that process will take is pretty uncertain, but if we see another 2+ weeks of warm ridging aloft I do expect the fog will eventually lift as surface moisture slowly fades (and as the ECMWF ensemble does eventually depict).

Winter seasonal outlook continues to point toward warmer/drier tilt, esp. SoCal/SW (yes, even now!)

I’ve received a lot of feedback over the last few weeks to the effect of “Well, so much for that wet winter we were promised!” Well…I’ve got two things to say in response. First, no one with any credibility would ever promise a particular outcome on the basis of a seasonal forecast; at best, the state of the science allows us to foresee “tilts in the odds” in one direction or the other under some circumstances. Sub-seasonal patterns can diverge strongly from seasonal predictions, especially in the transition seasons of autumn and spring, to the extent that they result in different or even opposite outcomes from early predictions. (So if someone did actually promise you something, I’d suggest you ask for your money back!). But second: it isn’t even winter yet! Usually, winter predictions are for Dec-Feb (or sometimes even Jan-Mar); so far, it is looking that December will likely turn out to be a drier and warmer than average month for most of California. We’ll see what the rest of the season holds, but the winter is mostly still in the future tense!

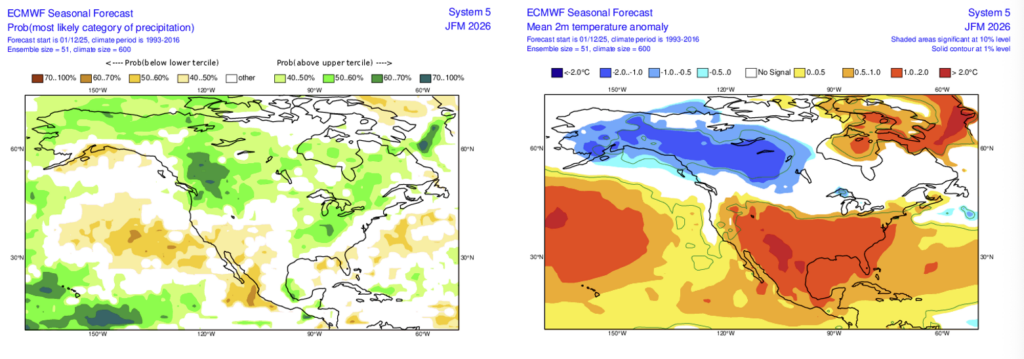

And to that point: the latest ECMWF seasonal outlook was released last week (other model ensembles to follow next week). It continues to suggest a tilt in the odds toward drier/warmer than average conditions across southern/central CA and the lower Colorado basin this winter; with an ongoing La Niña event and persistent V-shaped warming pattern in the Pacific, that still seems reasonable to me. One wildcard continues to be the really warm ocean temperatures along the CA coast and extending thousands of miles offshore, so any storms that do arrive might continue to be a bit warmer, wetter, and more unstable than usual (so potentially juicing up precipitation totals as occurred in the fall). Exactly where that leaves us at the end of the season remains TBD, but it’s a combination we’ve seen not infrequently in recent years.

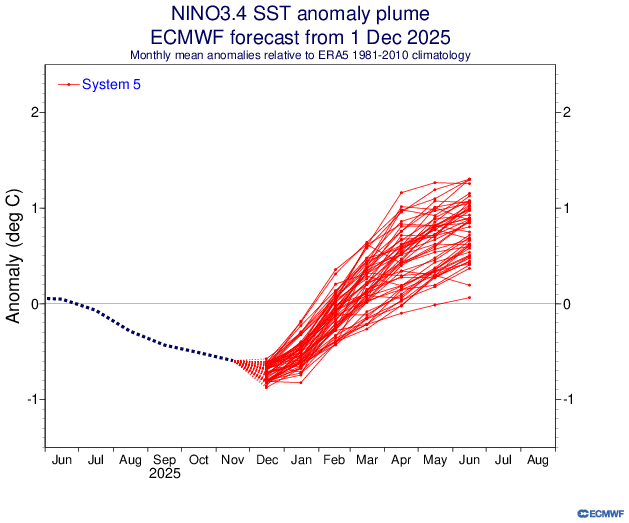

Looking a bit farther ahead, it does appear that the present La Niña conditions will begin to fade soon and then disappear by late winter or early spring. The ECMWF ensemble as well as other coupled ocean-atmosphere models are presently pretty enthusiastic regarding a possible rapid transition toward El Niño conditions by early summer 2026. That would be, circumstantially, supported by an especially strong westerly wind burst in the West Pacific right now that may allow a fair bit of SST warming in the tropics to expand eastward in the coming weeks/months. But ENSO predictions are tricky this far in advance; the models have gotten noticeably better over the years in this respect, but they tend to still be a little overly sensitive to initial conditions (so they could be “over-reacting” to the ongoing westerly wind burst). I’ll be following in the coming months!

Last week, I offered a broader global climate update during a special live office hour session. While the bulk of this conversation focused on longer-term temperature and greenhouse gas trends, I also did spend some time toward the end of the session discussing recent ENSO trends and the outlook for the next 6 months or so. Please do check it out!

An invitation: Join me for a live virtual event on Wednesday morning discussing hurricane trends in a warming climate!

This will be an event focused on an atmospheric science topic we don’t have occasion to talk as often about on Weather West because such events are rare along the West Coast, but which is nonetheless quite important in the national-to-global context: the once-predicted (and, now, observed) increase in rapidly-intensifying tropical cyclones (i.e., hurricanes) in a warming climate. This event, which is hosted by Reask and will feature Steve Bowen and me in live conversation, will touch on both the science behind and the practical implications of intensifying tropical cyclones in a warming world. I plan to discuss how some of the very same broader thermodynamic trends are driving rapid and often under-anticipated increases in phenomena as diverse as wildfires, severe thunderstorms, and hurricanes–but I’m sure there will be some other interesting and worthwhile tangents as the live conversation evolves, as well.

The event is going to be quite early in the morning U.S. West Coast time as it’s aimed at an international and U.S. East Coast audience, but for those early risers and caffeine aficionados out there, perhaps I’ll see you then. Event details: 7-8am Pacific Time on Wed., Dec. 10. Free registration required.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.