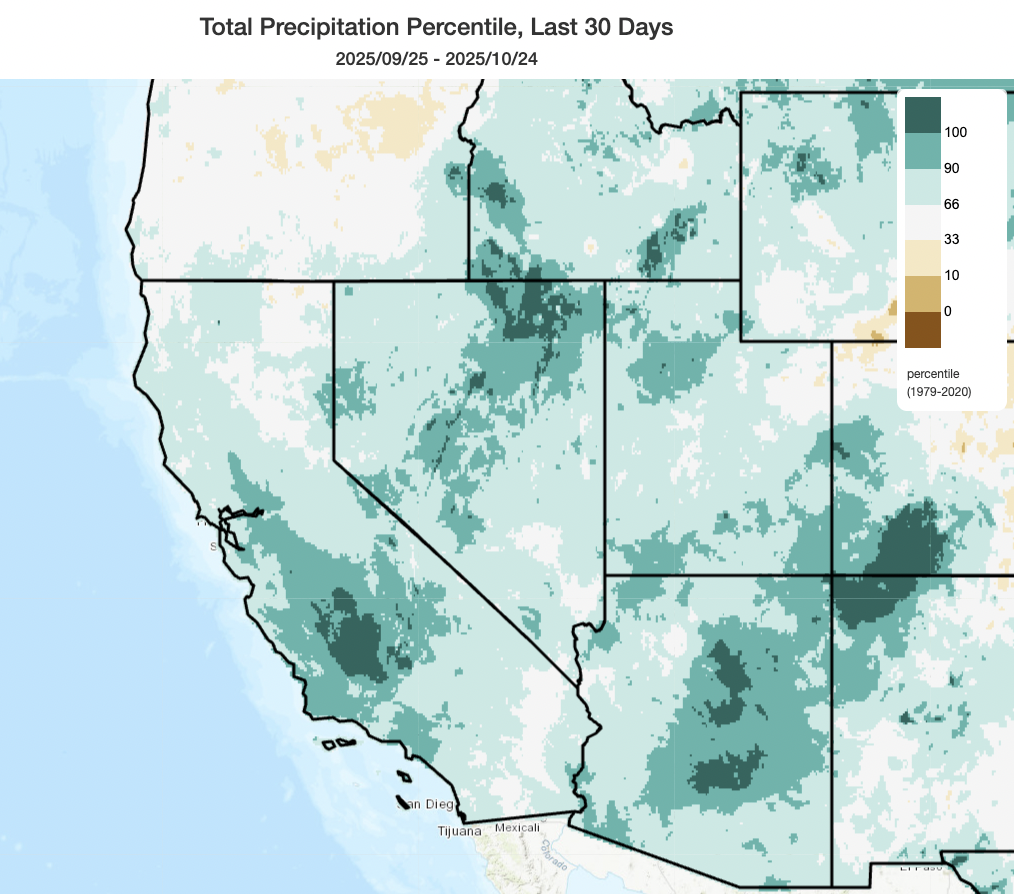

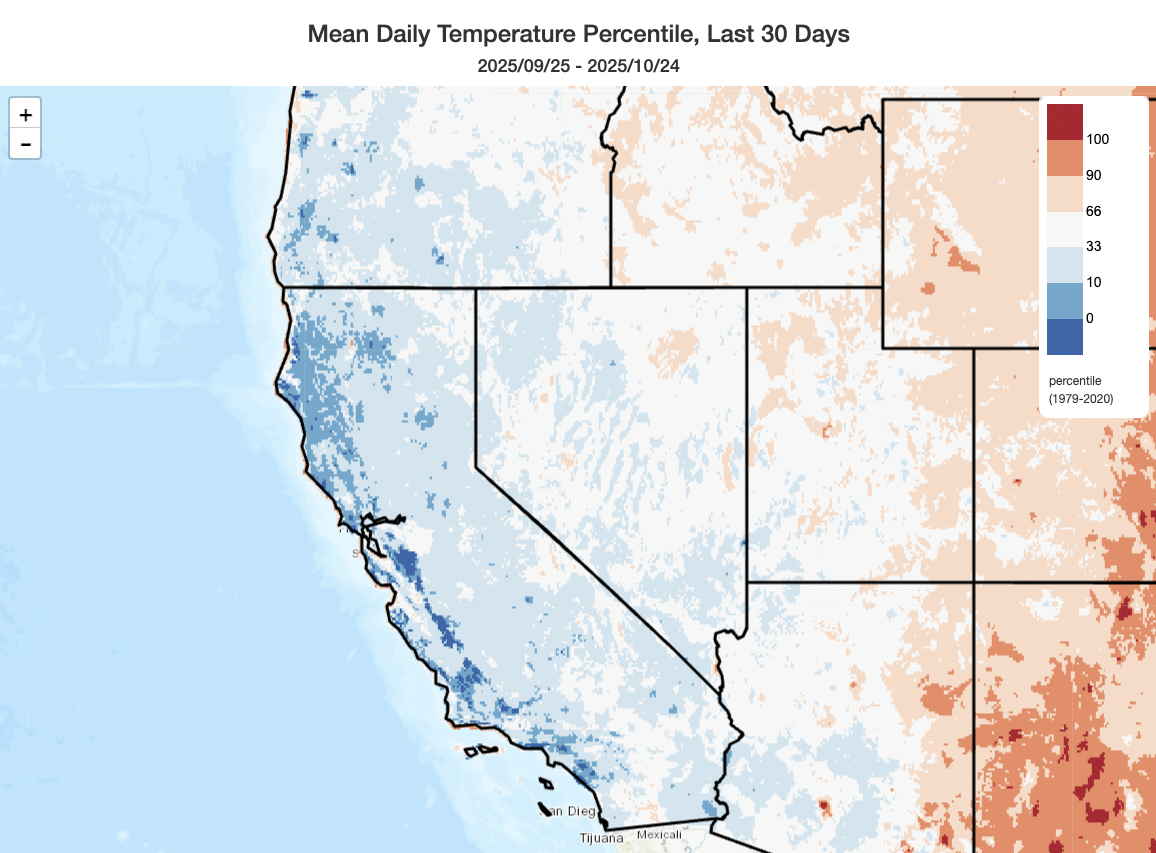

A notably wet (and also cool) October across nearly all of California and much of the Southwest

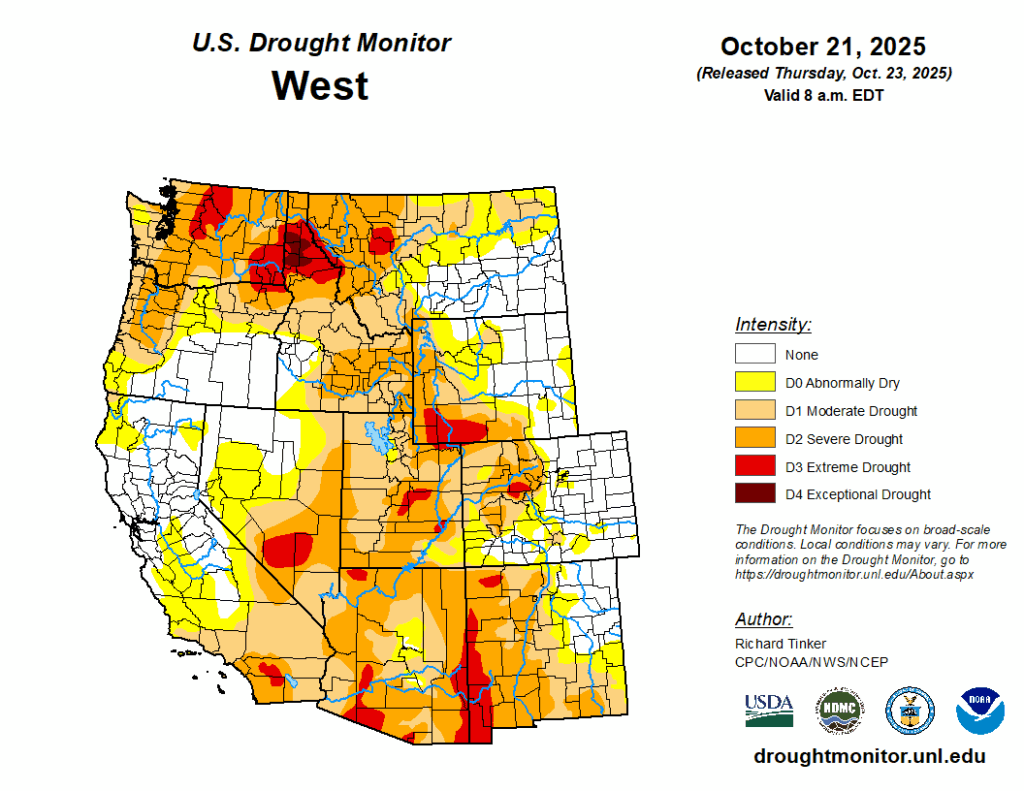

2025 has been a decidedly strange weather year in California–starting with January’s devastating Los Angeles-region firestorms amid a record-dry 6-9 period (and following near-record wet conditions over the 1-2 years prior). The spring and early summer were notably cool by recent (climate-warmed) standards–in fact, some coastal and near-coastal locations saw their coolest start to summer in over 30 years. With a couple of modest exceptions, the rest of summer (though notably warmer, and in most cases slightly warmer than even the recent average) lacked episodes of extreme or statistically/historically exceptional daytime heat, though persistently above-average overnight temperatures became widespread starting later in August. The exceptional basin-wide North Pacific marine heatwave, meanwhile, did eventually make it all the way to the U.S. West Coast (including CA), where well above average near-shore and offshore temperatures persist even as of this writing. Coupled with some unusual early season weather systems (including a litany of cut-off lows from Sep into Oct), these warmer than average coastal ocean temperatures helped “juice up” the atmosphere over California to produce unusually abundant showers and even thunderstorms occurring in repeated rounds across much of the state. October, in particular, was a pretty wet month in California–but even more so in the interior Southwest, including parts of the Four Corners regions that saw near-record dryness during the summer monsoon season that experienced record rainfall in October and subsequent severe local flash flooding. And, fortuitously, well-timed though climatologically anomalous rain events during summer and fall turned what could have been a pretty severe California fire season into a much tamer one to date (January, of course, excepted).

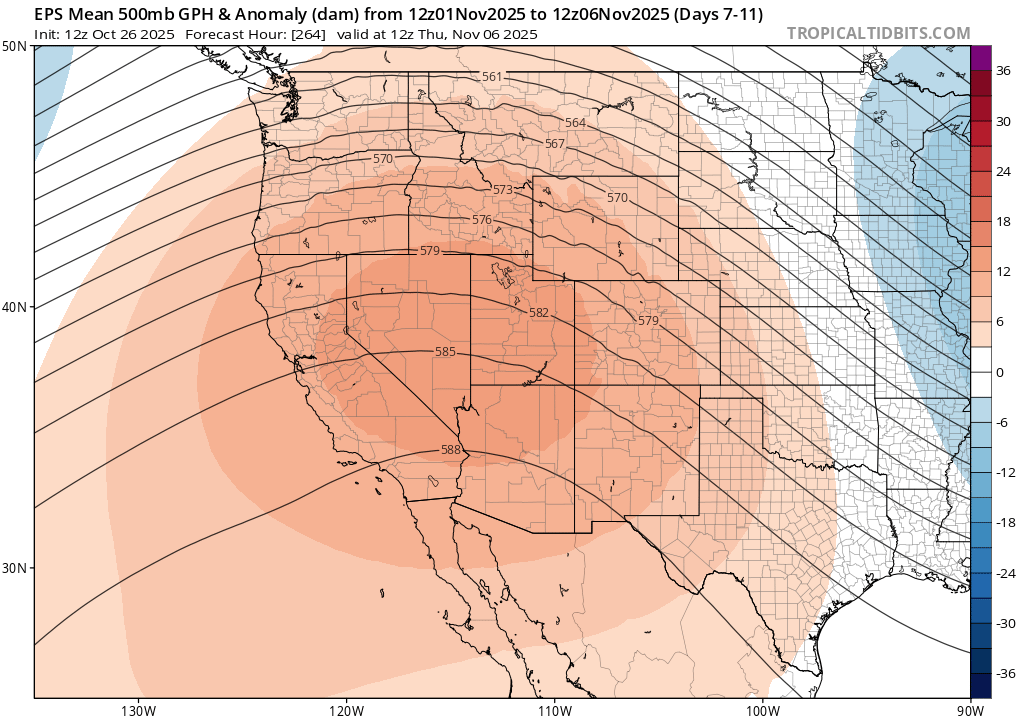

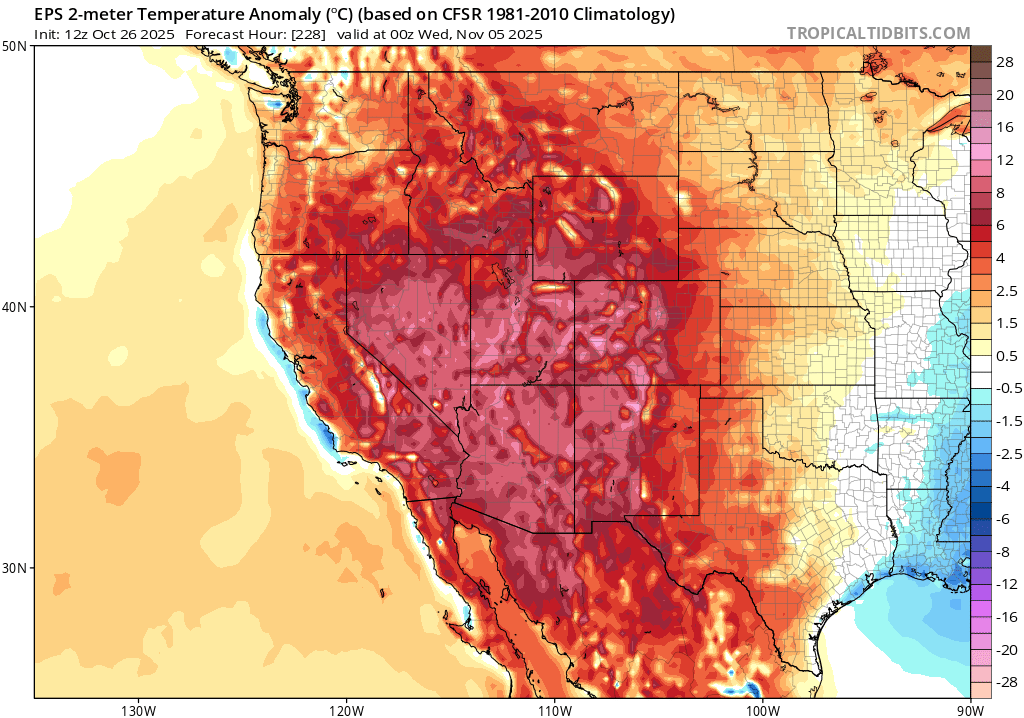

All signs point to a very different November ahead: persistent & possibly strong ridging, anomalous warmth, and mostly dry weather

Despite the recent coolness and wetness in California (and even some ongoing NorCal showers as I write this blog post), late October and most of November are currently shaping up to be quite different. There is strong inter-model ensemble consensus that a fairly strong, broad, and persistent ridge will build across during the West next week and linger for at least 2-3 weeks thereafter, bringing an extended stretch of drier and much warmer than average conditions to most of the western U.S. and California. In fact, the next 2 weeks look to be completely dry across SoCal.

In fact, depending on the exact position and magnitude of the ridge, there could even be some fairly substantial heat (by November standards) in some interior valley locations as well as coastal SoCal; even the coast of NorCal will likely be quite mild as warmer than average near-shore ocean surface temperatures generally persist. The one exception could potentially be portions of the Central Valley, particularly in the north, where Tule fog could (both literally and figuratively) put a damper on things; this is often difficult to predict well in advance. But above that potential (very thin) fog layer, conditions even in the lower foothills and mountains will be mild and mostly dry.

For the most part, this will mean the period starting around Halloween and continuing, perhaps, toward Thanksgiving will feature mostly quiet and pleasant weather conditions across California! It’s possible a couple of systems sneak through the ridge and bring some modest NorCal showers at times, but central and southern CA especially appear likely to stay dry for the foreseeable future.

Substantive wildfire season likely over in NorCal, but probably not over in SoCal

I’ve received a lot of questions from folks regarding what recent rains, and the overall unusual sequence of weather events, mean for California wildfire. I’ll discuss this at some greater length in tomorrow’s livestream (see below), but I did want to reflect a bit on this here. Generally speaking, we’ve received multiple soaking rainfalls in NorCal (including essentially all regions from around the Interstate 80 corridor northward, and also the entire Sierra Nevada chain) such that we’ve likely achieved “fire season-ending” moisture levels in local vegetation. A quick check of vegetation moisture levels and aggregate flammability indices across NorCal suggest all locations have near to above-average vegetation moisture for late October, and near to below-average flammability. While some fires, mainly in finer fuels (like grasses) that can respond faster to episodic warm/dry periods (like the upcoming one in November), remain possible, it’s quite unlikely at this point that there will be consequential wildfires the rest of the season from around the SF Bay Area northward (or in the Sierra Nevada). But you might well see some smoke plumes in the coming weeks–and that’s because conditions are looking quite favorable for risk-reducing prescribed fire treatments during a prolonged dry spell following substantive rainfall. Local temperature inversions might prevent this at times in places where unwanted smoke can become trapped near the surface, but otherwise this looks like a notably favorable window for getting some “good fire” on the ground.

In SoCal, current conditions are actually similar to NorCal in that vegetation moisture is near to above average for late Oct (and, thus, flammability is lower than average). But here, I don’t think we can safely declare fire season over–especially with a prolonged period of anomalously warm and dry conditions coming up. Recent precipitation, however, does put is in a very different position than this time last year, when some of the driest condition on record were rapidly developing in the Southland leading up to the devastating January 2025 fires. We simply don’t have that precondition in place this year. That said, several weeks of warm and dry weather will start to bring fuel moistures back toward and even below average values for November–portending the potential for occasional wildfires to start popping up again. Should there be a major offshore wind event later in November or December following weeks of relative heat and dryness, critical fire weather conditions (and, thus, the risk of significant wildfires) could potentially arise again even though conditions are presently nowhere near the level of exceptional aridity we had from Oct-Dec 2024 and there are no major offshore wind events currently in the forecast.

Some more thoughts on Winter 2025-2026

November, as mentioned above, appears quite likely to end up as a drier and warmer than average month essentially statewide (and perhaps even region-wide across the Southwest). But what about the rest of winter?

Folks who are longtime readers of Weather West know that I like to offer “informal” seasonal outlooks, and always emphasize the considerably caveats and uncertainties involved. That’s because such predictions are inherently “probabilistic” (as opposed to “deterministic”)–and thus can only reasonably be evaulated on a long-term basis (i.e., across many years of predictions) and not simply on a year-by year basis. This is because the embedded predictive signals are often weak, and even in years when there are somewhat stronger indications of anomalous conditions at seasonal scales the “unpredictable” aspects of our coupled Earth system can easily overwhelm them, thus resulting in outcomes that diverge from cautious “tilt in the odds” outlooks.

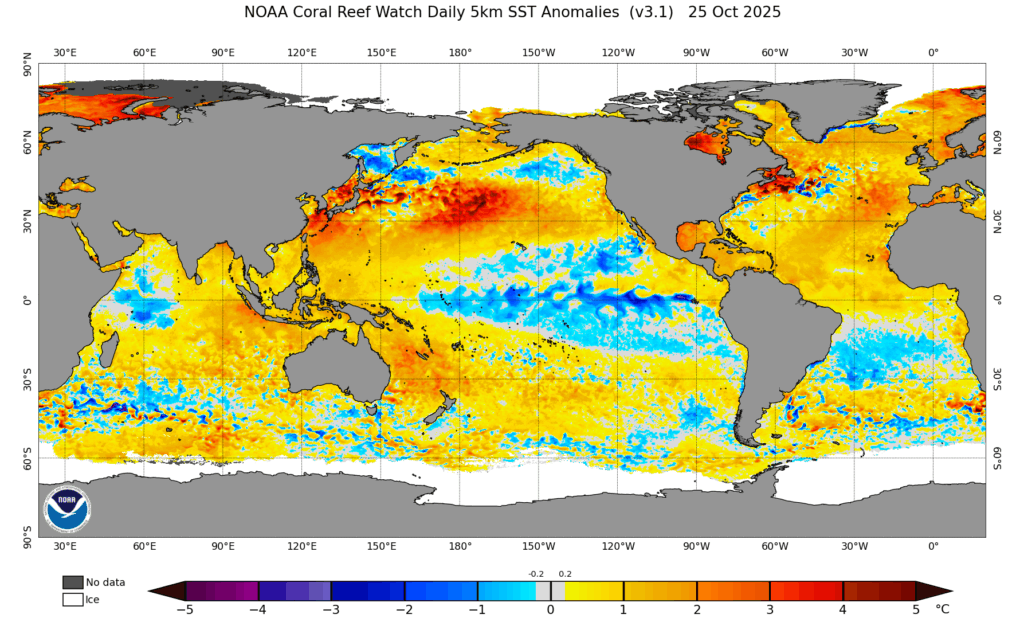

This year is no exception, but there are definitely some interesting things to discuss. First and foremost, we have a historically anomalous (or even unprecedented, by some metrics) combinations of an exceptional and long-duration marine heatwave in the North Pacific bringing well above average ocean surface temperatures across nearly the entire basin outside of the tropics. In the tropical Pacific, meanwhile, we have La Niña conditions (cooler than average ocean temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific) in place. This overall set-up means two things: 1) that the overall latitudinal surface temperature differential over the North Pacific is weaker than usual, and that this weaker gradient might allow this La Niña event to “punch above its weight” in terms of its effect on global weather patterns, and 2) that the atmosphere will have a whole lot of extra water to work with thanks to enhanced evaporation from a much warmer than average ocean over nearly the entire Pacific storm track region. Finally, there is a third factor at play: the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO, a semi-periodic stratospheric wind pattern reversal) appears to be entering its easterly phase in late 2025, which will affect the teleconnections we might otherwise expect from a modest La Niña event.

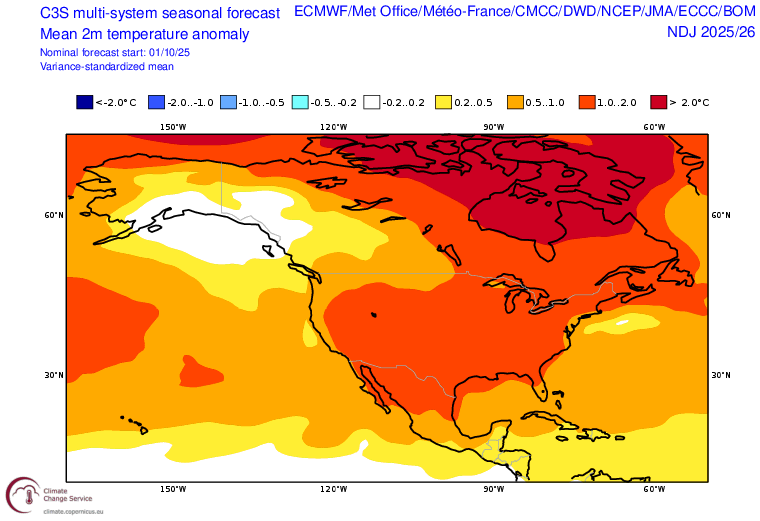

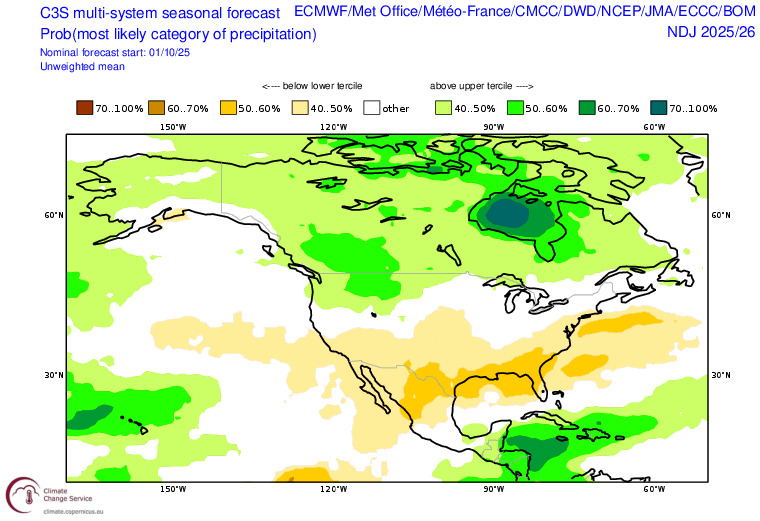

Overall, this means I expect that there will be, as is usually the case during La Niña events of sufficient magnitude (or, in this case, “effective magnitude”) , an anomalous ridge somewhere over the northeastern Pacific at seasonal scale. As always, though, that seasonal-scale ridge will interact with the mean flow (and jet stream) in different ways at different points in the seasonal cycle. Over the next ~2 months (in November and December), I’d generally expect this to mean fairly prolonged episodes of unusually dry and warm conditions across California, especially in the central and southern parts of the state. And this is, indeed, consistent with seasonal model projections suggesting well above average Nov-Dec temperatures across CA and most of the West as well as a tilt in the odds toward below average precipitation.

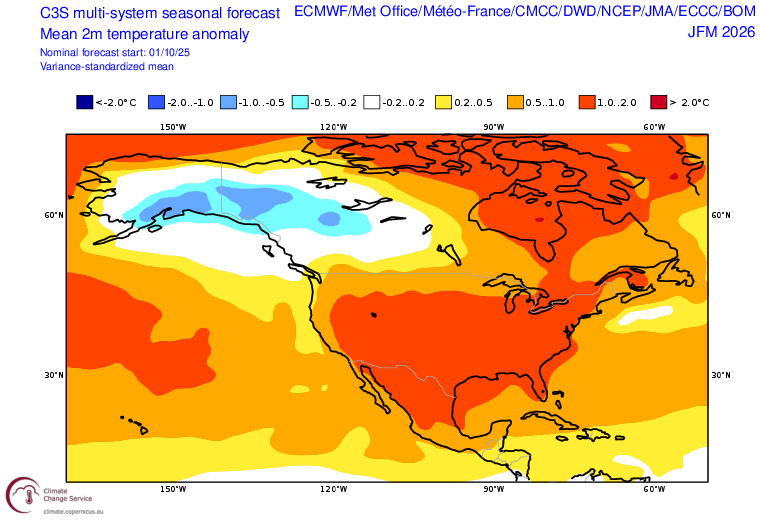

There may be a bit of a shift later in the season, though, from January onward. The easterly QBO often comes into play later in the winter, and tends to allow for greater disruption of the stratospheric polar vortex from ~Jan to Mar. In California, this is a bit of risky business in the sense that it’s a high stakes gamble: PV disruptions, which tend to be associated with a wavy jet stream and high-amplitude flow patterns, can produce either very warm/dry episodes or very cold/wet ones depending on exactly where the Pacific wavetrain sets up. Given La Niña conditions, I do in general think the odds of ridging that keeps at least SoCal and the interior SW warmer/drier than usual are pretty high. But there are also indications of a conspicuous cold pool developing over British Columbia later in the winter; if the ridge shifts westward even transiently during this period, it could result in some substantive cold air outbreaks and good periods of snow accumulation across portions of the intermountain West (and perhaps also the Sierra).

If that all seems a bit “handwavy,” well…that is still, unfortunately, seasonal prediction in a nutshell. (Maybe artificial intelligence and machine learning methods will help with this eventually, but so far gains have mostly been incremental in this respect–it remains a very hard problem, though that’s a topic for another day). But for my TL;DR summary: during winter 2025-2026, conditions will most likely start out drier and warmer than average (for Nov-Dec) across CA and the interior SW; a tilt in the odds toward drier than average conditions in SoCal (but wetter than average conditions in the PacNW, with NorCal sandwiched somewhere in between) will continue all winter though there is some increased potential for transient cold air outbreaks (even if winter remains warmer than average overall, which is likely) and subsequent opportunities for mountain snow accumulation during those windows.

Join me live on YouTube on Monday, Oct. 27 at 3pm Pacific Time for a “double header” session

On Monday afternoon, I’ll host a special “double-header” livestream session. First, I’ll discuss the dynamics, potentially devastating impacts, and broader context surrounding exceptionally intense (likely category 5 by the time of session) Hurricane Melissa in the Caribbean as it makes a final approach on Jamaica. Later, I’ll bring the focus back to California and the western U.S.–and will discuss the potentially very warm and dry November weather to come and what it means for fire in California (both wild…and also prescribed!). See you then.