Persistent subtropical ridge produces an extraordinary precipitation dipole in northern vs southern CA

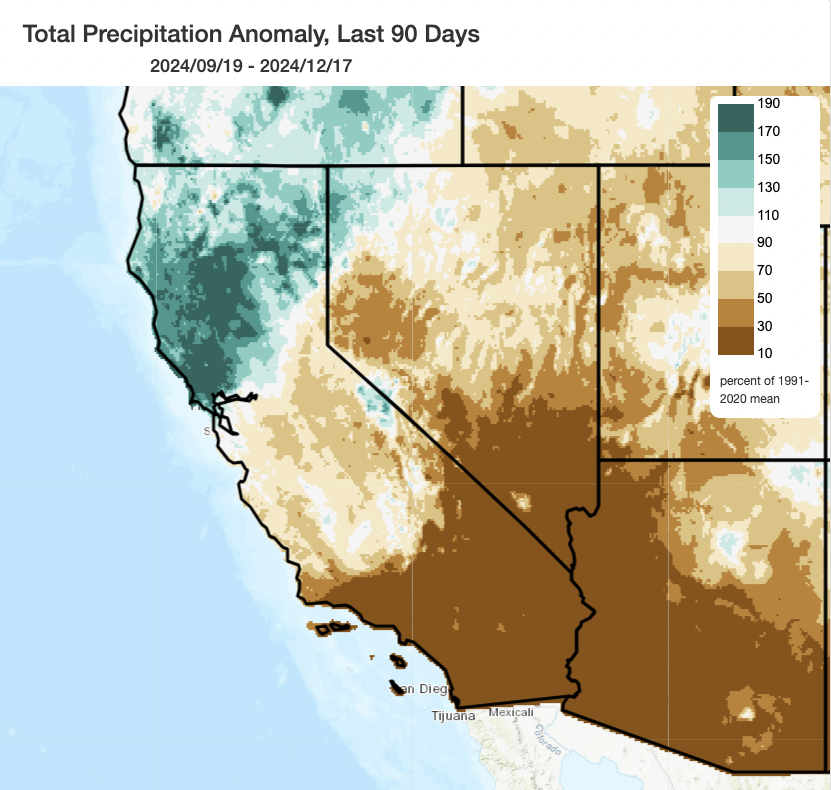

When it comes to California precipitation so far this season, your mileage may vary. Specifically as a function of latitude! Since October 1, nearly all of NorCal north of the Golden Gate has seen much wetter than average conditions; south of Point Conception, conditions have been much drier than average (and even completely dry in some cases). In fact, there are pockets of Sonoma County that are still on track to experience their wettest start to the Water Year on record–and wider swaths of SoCal that are on track to meet or tie the records for their driest start to the Water Year on record. Even in a state where there are frequently striking north-south contrasts, the extremity of the current north-south precipitation dipole is genuinely remarkable–a north-south contrast that may itself be record-breaking in some respects.

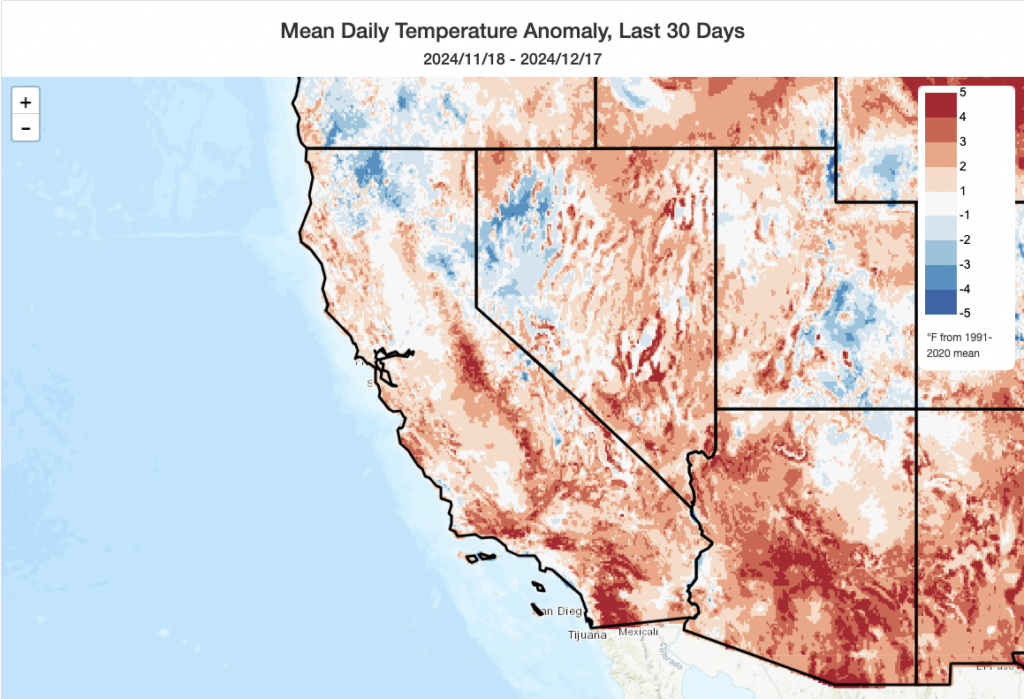

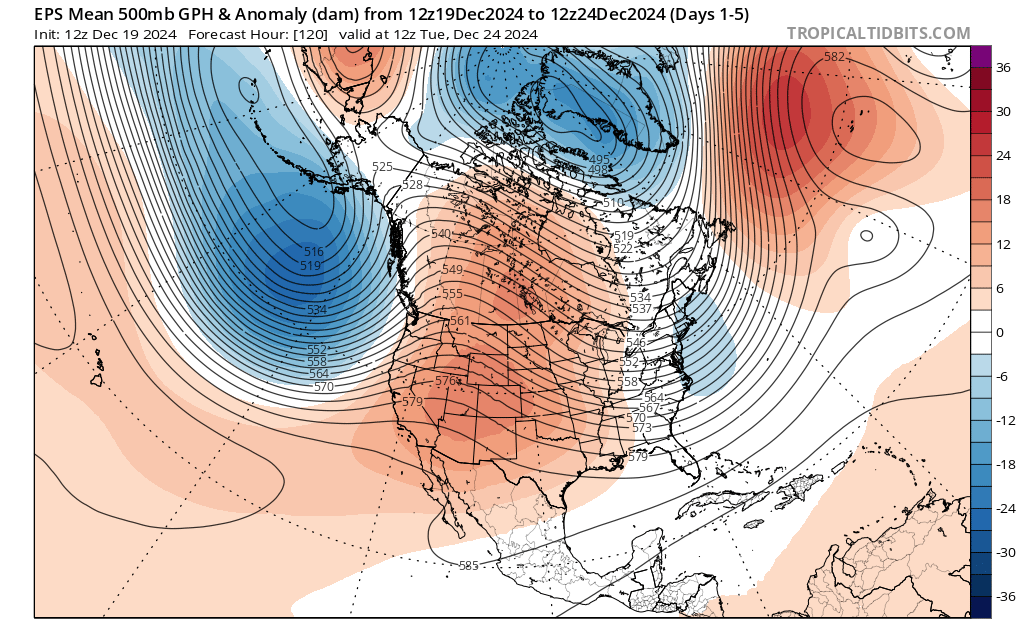

The proximal culprits? Persistent, anomalous, and broad subtropical ridging combined with a notable (but not quite so persistent) anomalous low pressure center located west of Washington and Oregon in recent weeks. Strengthened jet-level winds at the boundary between these two systems has directed the storm track, and a firehose of relatively warm and very moist Pacific air, across the Pacific Northwest and also northernmost California (occasionally making it as far south as the Bay Area or Central Coast). This pattern has managed to produce a very sharp gradient of precipitation during many recent storm events, with only 20-40 miles separating regions with significant flooding from those that remained mostly dry. Temperatures in this regime have been almost uniformly warmer than average across California, though this has been of the “warm and wet” flavor in NorCal and “warm, dry, and occasionally windy” flavor in SoCal (with occasional episodes of high wildfire risk continuing down south as a result).

A remarkable, damaging and injury-producing tornado in Santa Cruz County

Last weekend, a relatively compact but potent low pressure system strengthened upon approach to the NorCal coast, making landfall near San Francisco. The cold front itself was highly dynamic, and was especially notable for the robust convection (thunderstorms) contained with it. Widespread lightning and fairly numerous reports of damaging winds occurred; a probable waterspout spin-up west of the city of SF that threatened to move ashore triggered the city’s first-ever Tornado Warning from the National Weather Service. (While significant wind damage was indeed reported in SF proper from this line and individual storm cell, it appears that damage was likely from straight-line winds vs. an actual tornado.)

The most dramatic event, however, came later in the afternoon long after the cold front had passed but as numerous strong convective showers/thunderstorms rotated from northwest to southeast on the backside of the low. It was in this environment that a strongly rotating mini-supercell storm formed offshore of the Santa Cruz County coast (possibly producing an offshore waterspout) and then inland across the western slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains–ultimately producing a notable tornado in Scotts Valley as the storm moved upslope. This tornado (ultimately designated an EF-1) was powerful enough to flip occupied cars and trucks (including a CalFire vehicle), knock over trees and power poles, and damage roofs. Several injuries were reported, as well.

Tornadoes are certainly unusual in California, though also not nearly as rare as many believe (there are 5-10 in a typical year in the state, most often occurring in the Central Valley or the coastal plain of southern California, especially LA County, between November and March). But substantially damaging tornadoes, especially ones that produce multiple injuries, are considerably rarer in CA–and the setting of this particular event (essentially within a valley surrounded by the Santa Cruz Mountains) makes it even more so.

If you are interested in a much deeper dive into the broader context of this specific tornado, as well as some further discussion on tornadoes in California, I’d encourage folks to check out my recent livestream (which was recorded, as always).

Rest of calendar year looks warm; (very) wet far north and (very) dry far south. Yes, still.

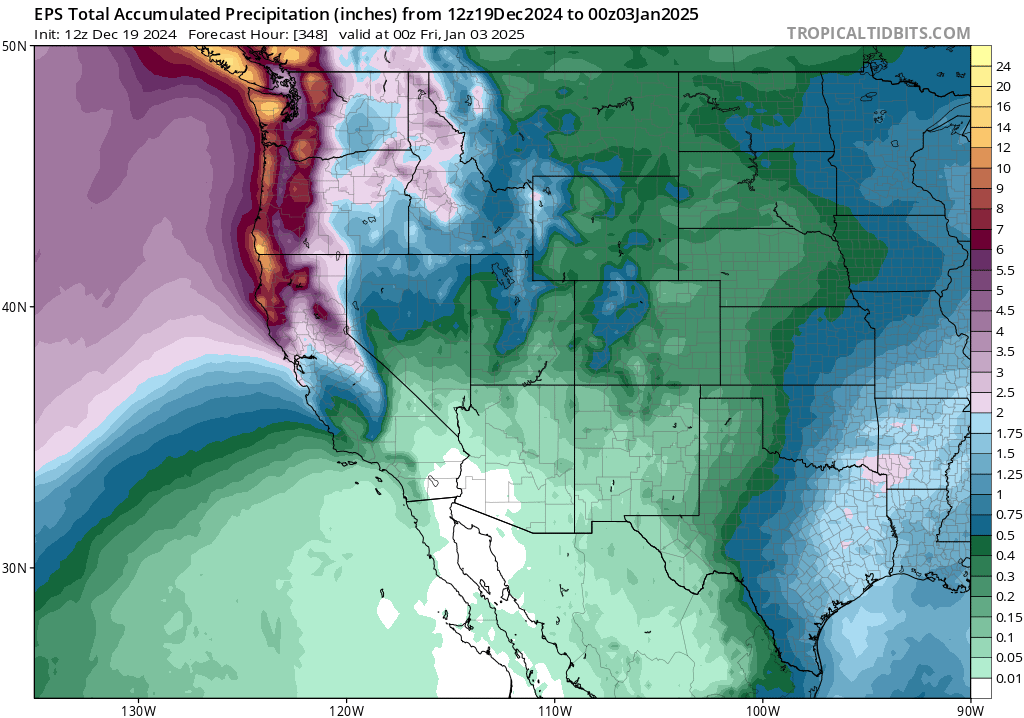

Well, it looks like California is in for more of the same over the next 7-10 days at least as subtropical ridging continues to coincide with a persistent low west of Washington to drive a parade of warm, wet atmospheric rivers into the Pacific Northwest and CA North Coast/northern mountains. Rain will also fall, more occasionally and at times (and it could be briefly heavy) as far south as the SF Bay Area/Interstate 80 corridor. South of that, there is more uncertainty–but there is a decent chance that central CA (from coast to southern Sierra) will see at least some light precipitation over the next 2 weeks. South of Point Conception, including Los Angeles and San Diego, prospects for more than a few sprinkles appear pretty meager still. There’s a 20% chance that some more substantial rain could make inroads that far south, but right now it appears there is a decent chance that little or no meaningful precipitation will fall across much of SoCal through the end of the calendar year (while far NorCal and the PacNW continue to be inundated–further accentuating the existing precip anomaly dipole pattern).

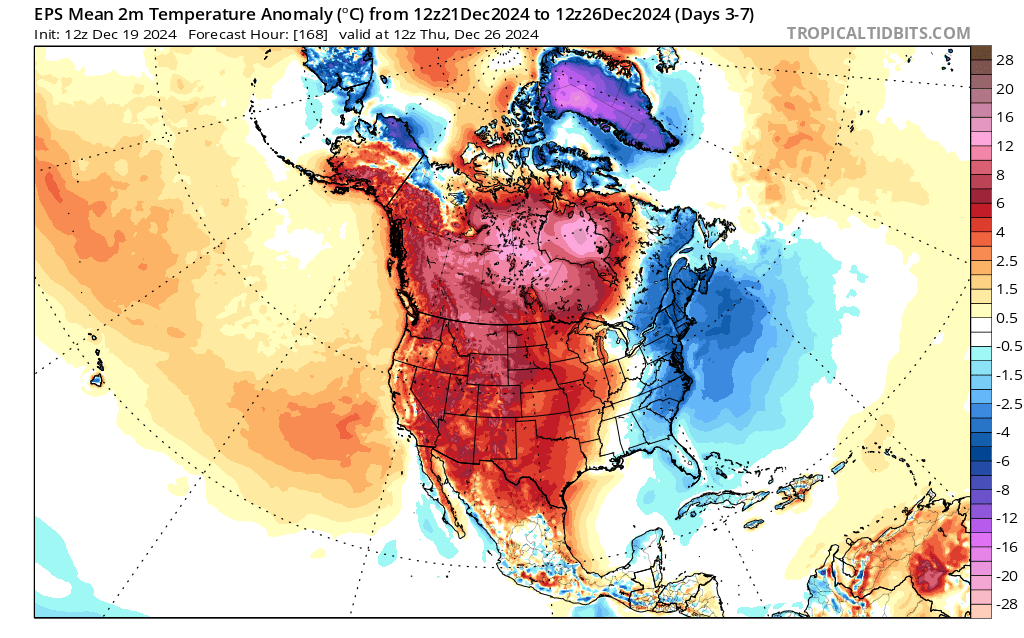

Over this period, conditions look to be exceptionally warm across most of North America as very warm/moist Pacific air is advected eastward across the continent. It’s even possible that some locations in the Rocky Mountains could see rain (yes, rain–not snow!) next week; record high temperatures for late December are possible across some interior regions and wildfire risk will continue to remain elevated for this time of year across SoCal and parts of AZ. Some cooling in CA may occur after Jan 1 as the subtropical ridge amplitude moderates a bit, but overall there is not much of a cold air reservoir to speak of anywhere over North America so major cold outbreaks remain pretty unlikely.

What happened to La Niña? And what about the rest of the rainy season?

There have been various rumblings about La Niña (or its purported absence) in the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean this year. Early predictions hinted at a rather strong potential event, and that does indeed not appear to have materialized. Yet others have argued the La Niña is a total no-show, and therefore won’t exert a meaningful influence this winter. I don’t quite think that’s true either.

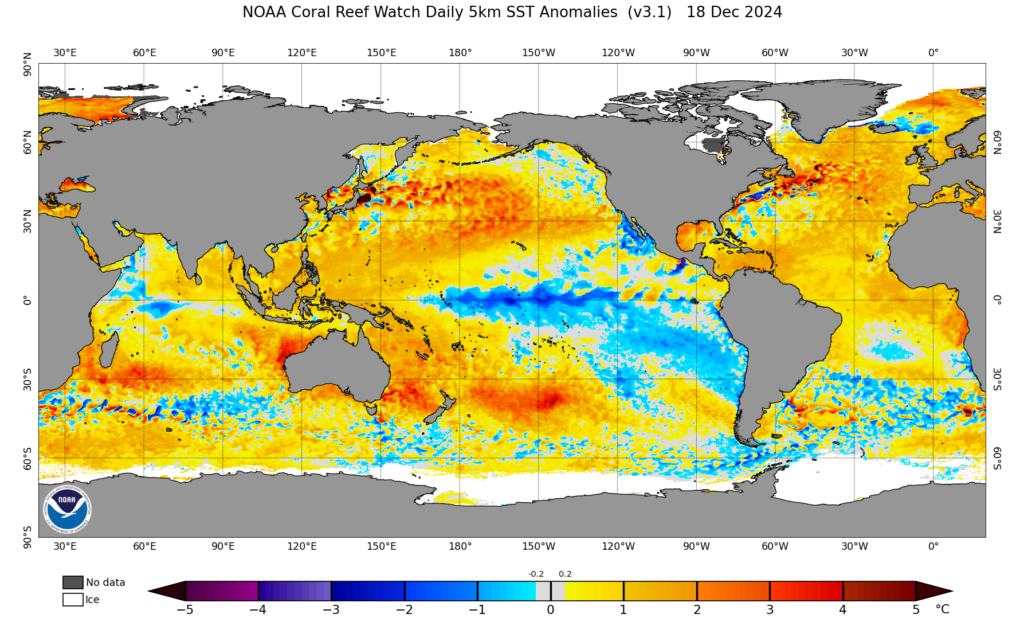

First, a quick glance at ocean temperature anomalies indicates a pretty broad region of anomalously cool tropical ocean temperatures, albeit centered farther west than during typical LN events. Additionally, there is the reality that the Pacific Ocean was warmed considerably in recent decades, yet that warming has been greatly muted in the key “ENSO 3.4” region used to define La Niña using a “temperature in a box” approach. That means that while the absolute Nino3.4 temperature anomaly might not be all that impressive, the spatial gradients in ocean surface temperature are much more impressive–and is more illustrative of a solidly mid-grade La Niña event (versus a marginal or non-existent one). Since it’s generally the spatial distribution of ocean surface temperatures that drives ENSO teleconnections, rather than their absolute values, one might expect the former to more directly relate to the behavior of the atmosphere–and so far this season, that’s exactly what we see. (See the excellent NOAA Climate blog post, linked below, for more details).

So, we’ve got a moderate-strength “relative La Niña” in place at the moment. And there is also clearly apparent, glancing at global ocean temperature anomaly maps as above, a re-emergence of the “V-shaped” warm anomaly pattern across the entire Pacific Basin that has been widely noted in recent decades and increasingly implicated in the (somewhat unanticipated) Southwest U.S. drying trend over the same period.

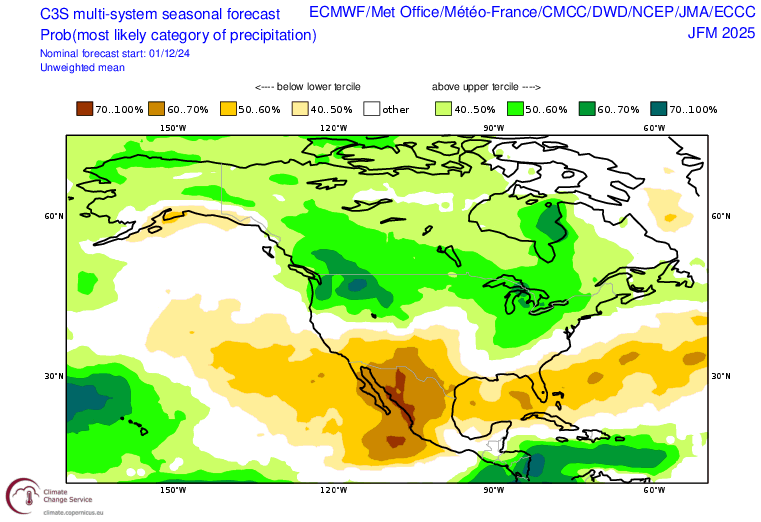

What does all of this mean, in context? Well, the recent pattern is somewhat consistent with what we have seen historically during many historical La Nina years (i.e., a very wet start in the PacNW extending into far NorCal, with dry conditions across SoCal). Often, the “dry lobe” of this pattern can expand a bit northward into central CA later in winter–and right now, this is exactly what the latest round of seasonal model outlooks from the global ensemble look like. In fact, the most recent update cycle in December continues to depict unusually high confidence in a continued “dipole pattern” along the West Coast, with a fairly strong tilt toward drier than average conditions Jan-Mar across SoCal and the Southwest and wetter than average conditions in the Pacific Northwest. As is often the case, there is not really much of a signal for NorCal north of about SF–so the wet pattern could well continue later this winter there, much as it could also moderate (really not possible to discern).

It’s worth noting that I don’t think this relatively strong dry signal for the remainder of winter in SoCal is solely a response to La Niña, relative or otherwise. Instead, I think a good portion of this is likely arising from the anomalous warmth in the western tropical Pacific (i.e., not LN-related), as well as the overall Pacific Basin “V-shaped” warm pattern. Time will tell, as always, but it’s likely that this winter will be quite different than the last two (which were both exceptionally wet) in SoCal.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.