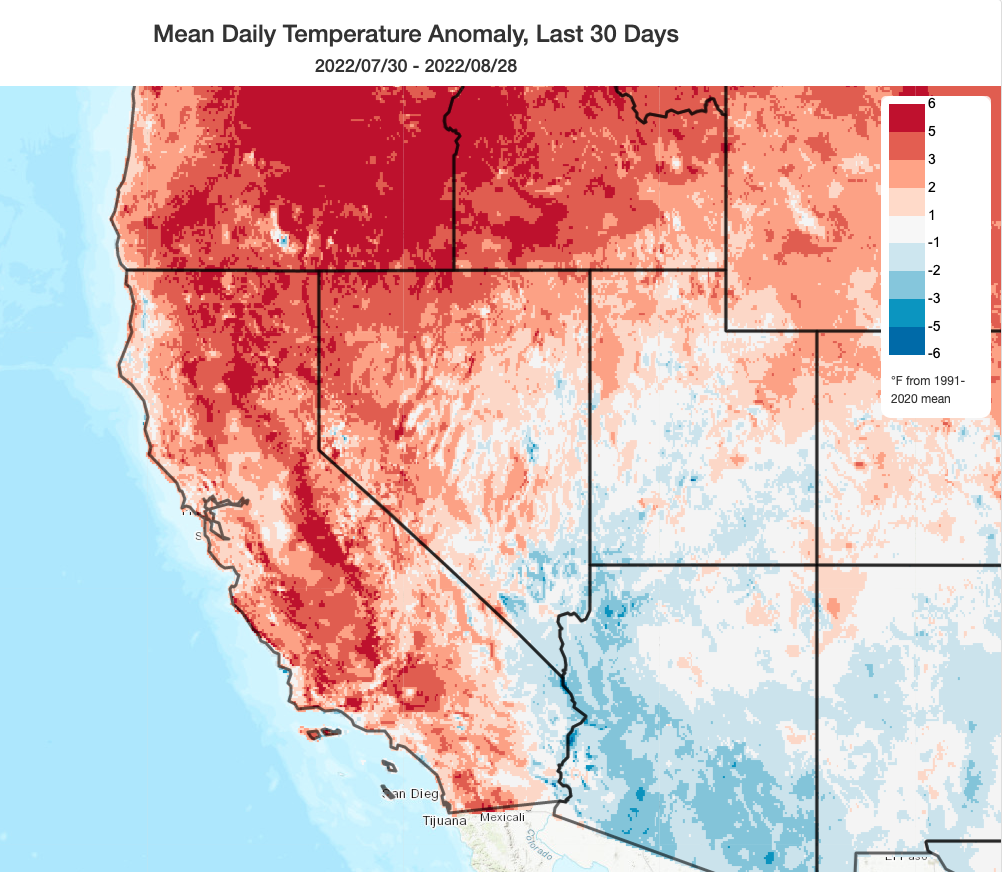

The last month: steadily elevated anomalous heat, especially inland

The past month has been warmer than August averages across nearly the entire state. There have not really been any extreme heatwaves, but these steadily elevated temperatures have yielded what will ultimately be another much warmer than average month in California. Although wildfire activity has been relative modest in recent weeks, vegetation drying has continued at a near-record pace for the date due to these much warmer than average temperatures and the legacy of long-term severe drought nearly everywhere. This sustained, but modest, antecedent warmth will amplify the impacts of what now appears likely to become quite a severe heatwave in the coming days (discussed in detail below).

Dangerous, prolonged, and likely record-breaking heatwave peaks Labor Day

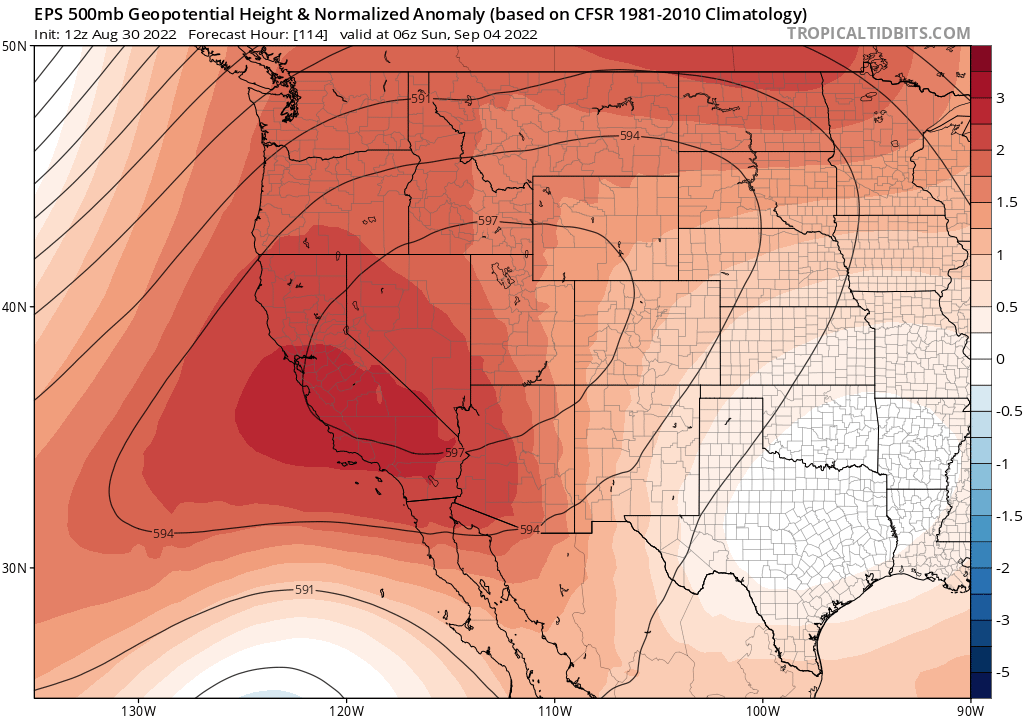

An extreme, and in some cases possibly historic, heatwave will unfold over nearly all of California over the next 7 days (or longer). This heat event will be remarkable in at least three distinct ways:

1) Daytime high temperatures will be extremely high across inland areas, particularly the Sacramento Valley and the inland valleys of southern California (but also elsewhere).

2) Overnight minimum temperatures will be greatly elevated in many areas, even relative to more ordinary heatwaves. This will be especially true in the middle elevation thermal belts.

3) The duration of this event will be very long. In parts of SoCal, the heat is already building and will not relent for at least 7-8 days. In many areas, 7-10 consecutive days of 100+ degree days are likely, with some days peaking above 110F.

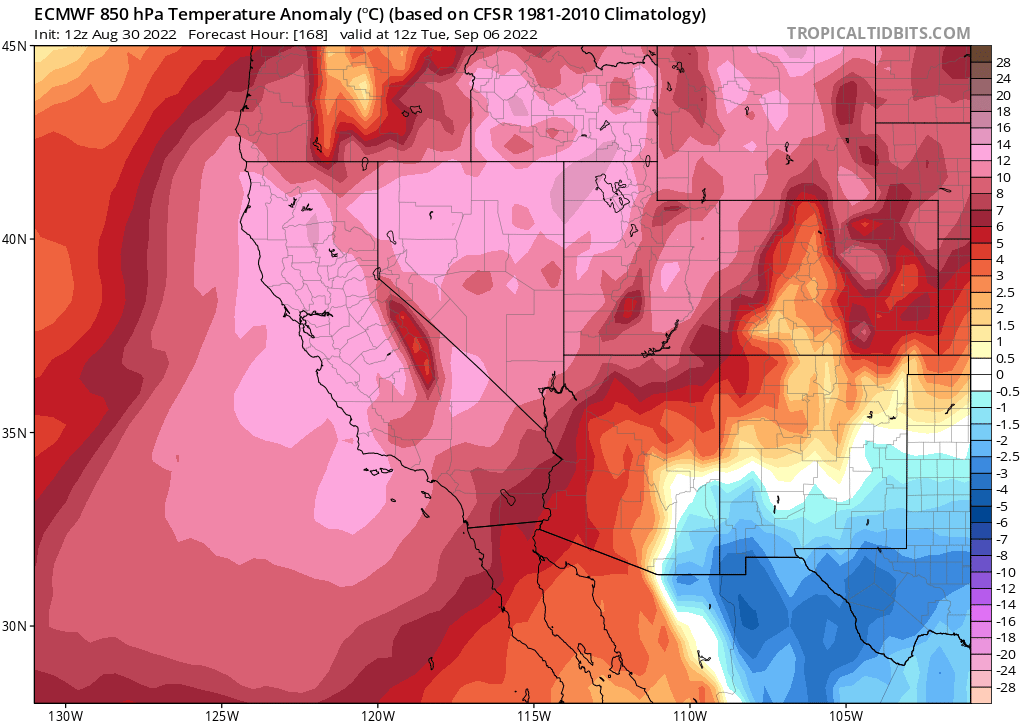

A ~600dm ridge will slowly build directly over northern and central California between Wednesday and Saturday, with temperature becoming progressively hotter each day from Wed through at least Sunday (and perhaps Monday). Peak temperatures are expected in most areas either on Sunday or Monday, at which time numerous locations across interior California are likely to set new all-time September monthly high temperature records. A few places, especially in the southern Sacramento Valley and in the San Fernando Valley, could even approach all-time, any-month temperature records.

Just how hot will it get? Temperatures in the Sacramento Valley and San Fernando Valleys will likely exceed 110F on multiple days, locally getting as high as 115F or even a bit hotter than that locally (!). For perspective, Sacramento’s all-time record high temperature is 114F (or 115F, depending on observing site). While the upcoming heatwave may ultimately fall just short of that historic benchmark, it will be a close call.

In the far eastern SF Bay Area, temperatures could approach or locally exceed 110F. Hot to very hot temperatures will be likely (especially Sunday and Monday) even in the near coastal areas; most of the Bay Area and the Westside of Los Angeles will probably be at or above 100F by that point. The extremely anomalous heat may not make it all the way to the beaches–there is still some uncertainty there. But recent historical experience with autumn heatwaves suggests that the models may be underestimating the extent of coastal heat, since it would only take a very weak offshore breeze to send beach temperatures skyrocketing in this kind of extreme “heat dome” pattern. Personally, I’d err on the bullish side there.

So, to summarize: there is high confidence in extremely hot inland temperatures that may break monthly records. There is lower confidence in how close to the coast the heat may ultimately reach, but there’s a good chance that near-coastal areas will get quite hot and even a chance that the beaches will as well.

This type of heatwave will be quite dangerous from a human health perspective–which is why there has been very strong language and messaging coming from local National Weather Service offices (including a slew of Excessive Heat watches and warnings that cover over 90% of California population). The prolonged nature of this heatwave, as well as limited overnight relief (especially in urban areas and topographical thermal belts) will be a major challenge. There are also some concerns regarding power grid stability amid a prolonged and severe event, especially in a year when hydropower is limited due to the severe drought. Any power outages or brownouts that do occur would have elevated impacts since they would disrupt mechanical cooling (air conditioning and fans)–so folks should be prepared for that possibility. Additionally, although winds are not expected to be strong with this event (fortunately), a long stretch of extremely hot temperatures and progressively lowering humidity will pose much higher wildfire risks that have been seen recently (especially given extremely dry landscapes amid the severe drought).

It is worth noting that the above numbers are actually a bit lower than the high-resolution models are currently spitting out for the Sacramento and San Fernando valley regions (with some values in the 116-118F range). Both the ECMWF and GFS have recently exhibited some positive biases in surface temperatures (i.e., the are running too hot) during extreme heatwaves in dry regions, so human forecasters are trying to take that bias into account (hence why some automated websites are suggesting even higher temperatures than expert-adjusted ones). My best guess is that these models are still running a bit too hot given the strength of the ridge, and I am currently shaving several degrees off of peak predicted surface temperatures from the raw ECMWF and GFS data. But there is a slight chance that actual observed temperatures could be a couple of degrees hotter than even the record-breaking values already noted above–hence at least the *potential* for all-time records in some places.

Expect a significant escalation in wildfire activity in early Sep

There have been some deadly (McKinney) and destructive (McKinney and Oak) fires already this season in California, so I hesitate to call it a “mild” fire season to date. But it is certainly true that the overall number of large/destructive fires has been significantly below the (decidedly hyperactive) benchmark of recent summers. Part of this is due to simple luck: despite record-dry vegetation conditions, we simply haven’t seen that many extreme fire weather patterns yet (i.e., extremely low humidity and/or strong winds), and we also had a mercifully mild and damp spring in NorCal. Another factor is likely the increasingly aggressive initial attack and heavy air support that have been used to respond to virtually all fires this year in the wake of recent disasters. We’ve also gotten lucky that potentially significant fire starts have thus far occurred more of less sequentially–rather than all at once–essentially allowing firefighting resources to focus on one at a time.

Unfortunately, I doubt this luck will persist past this week. The upcoming prolonged and extreme heatwave will likely mark the beginning of a significant uptick in fire frequency and intensity in the coming days/weeks, with increasingly many escaping initial attack as vegetation continues to be at or near record dry levels. This is especially true as autumn “wind season” approaches in both northern (and, later,) southern California. My fingers are crossed that luck remains on our side–especially when it comes to strong wind events in the coming weeks–but the reality is that any major heat, wind, or lightning event between now and the onset of the rainy season is going to pose a major fire weather threat given the state of the vegetation. And as the upcoming heatwave will likely affect a broad and already drought-afflicted region, including Oregon, Nevada, and parts of Idaho, it is very possible that Western U.S. fire activity will broadly increase in the coming days, resulting in resource drawdown as multiple fires compete for firefighting capacity. In other words: this fire season isn’t over yet, and will likely has a much higher peak than we’ve seen so far.

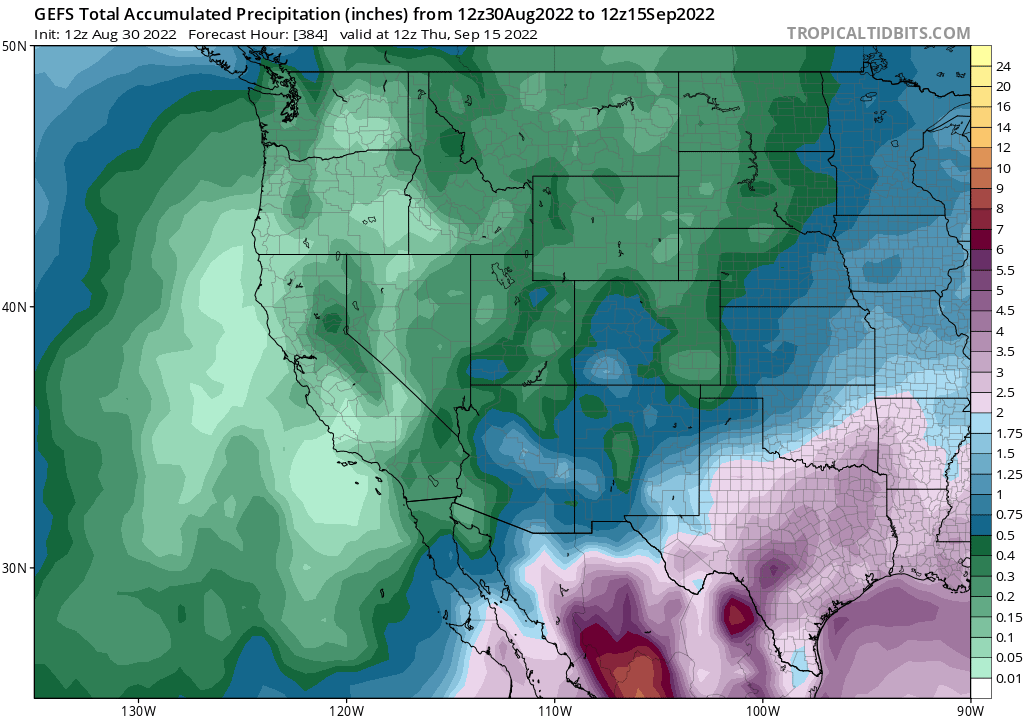

Long range hints: maybe some tropical remnants mid-Sep?

Although all eyes are presently on the potential for severe and dangerous heat over the next 10 days, there are also some hints of another type of weather pattern that sometimes occurs during autumn in California: the potential for some remnant moisture from a former hurricane to be advected across portions of California. This won’t happen for at least 10 days and won’t affect the upcoming heat event, but it will probably be something to keep an eye on in ~10-15 days as model ensembles have been hinting at this potential on and off for a while now. These types of autumn tropical remnant events can go one of two ways: occasionally, they produce meaningful precipitation that locally helps tamp down fire season for a couple of weeks.

But just as often, these remnants provide just enough elevated moisture and instability to generate high-based, and often dry, thunderstorms–which generate lots of lightning that go on to spark fires immediately prior to autumn wind season. At this point, it’s far too early to tell which outcome (if either) would be likely with any tropical remnants that make their way toward California this autumn–but since vegetation statewide is extra receptive to lightning ignitions due to ongoing severe to extreme drought, this is something that I’ll be following especially closely this season.

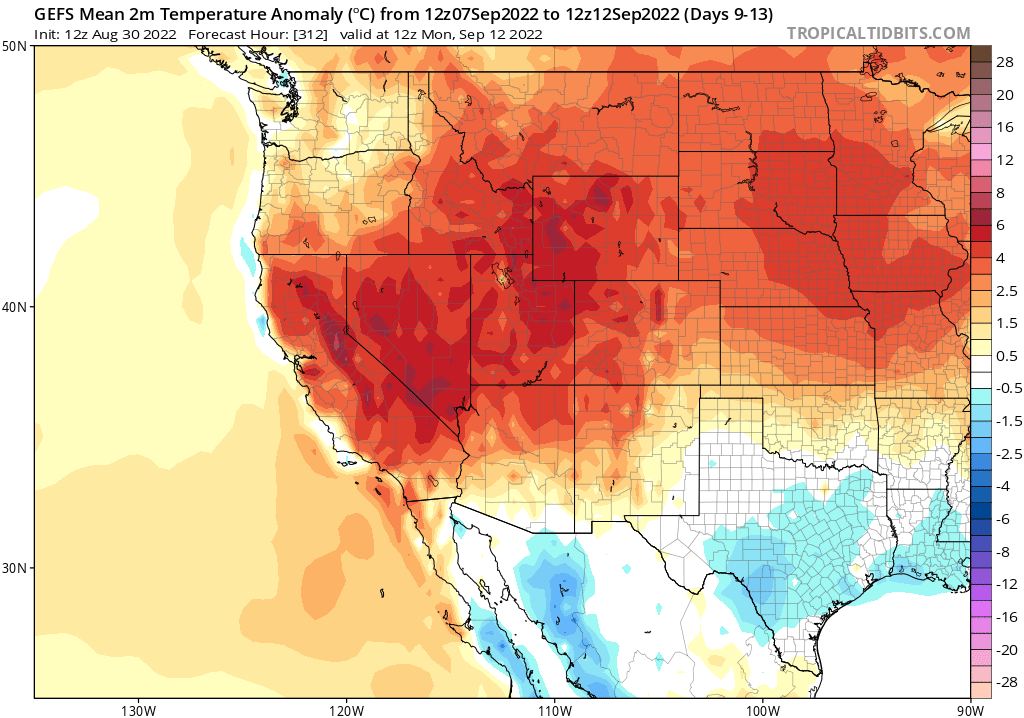

Irrespective of what happens to that potential tropical remnant moisture, though, it looks like hotter than usual temperatures will persist essentially state-wide–and nearly West-wide–for most of the first half of September. So although the extreme heat will likely fade away by the second week in Sep, it’s unlikely it’ll be replaced by significant cooling. Stay cool out there.

New research on dry lightning outbreaks in California

Recent work, led by my colleague Dmitri Kalashnikov at WSU Vancouver, takes a look at the seasonality and atmospheric conditions that produce dry lightning outbreaks over northern and central California. We found that nearly half of all warm season lightning strikes are “dry” (co-occurring with less than 0.10 inches of precipitation), and that in some regions that fraction is as high as 60-80%! Seasonally, dry lightning peaks over the mountains during July and August, but not until autumn (September-October) across coastal areas–including the San Francisco Bay Area. For more, you can read the full Twitter thread excerpted below, or access the open access paper itself.