As California’s record-setting drought persists, El Niño is rapidly intensifying in the tropical Pacific

Recent weather conditions

As has been the case with much of the 2014-2015 “wet season” in California, the past month has brought a decidedly mixed arrangement of weather conditions.

The past 30 days have been substantially drier than usual nearly everywhere, though there have been a few localized, notable exceptions. Convective activity (especially over the Sierra Nevada and other mountain regions) brought thunderstorms, hail, and heavy downpours in some spots. Localized heavy snowfall occurred late last week at the highest elevations, including substantial (and photogenic) accumulations along the Eastern Sierra near Mono Lake this past week. In fact, this mid-May snow burst may constitute the biggest snow event of the entire winter in some parts of the Eastern Sierra (which is more a testament to the abject lack of snow this year than the particular strength of the recent event)! Still, on a statewide and regional basis, Sierra Nevada snow water equivalent remains at an all-time record low for the date–as it has been now for the past two consecutive months.

2015 remains California’s the warmest calendar year to date as of May 1, though conditions have been somewhat cooler recently than during the period of nearly continuous record warmth that we experienced earlier this winter. Some coastal spots have actually been cooler during late April and early May than they were during the mid-winter months of January and February! This rather incredible climatological inversion owes itself to the recent return of near-coastal upwelling, which had been conspicuously absent for much of the winter. While water temperatures remain extremely warm just 100 or so miles offshore, coastal upwelling has kept places like San Francisco under a cool, moist (dare I say summer-like?) marine influence in recent days.

More spring showers to come

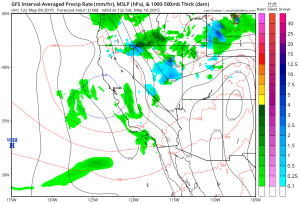

Another system similar to the one California experienced last week will approach the coast later during the coming week. Like the last several systems, precipitation on a statewide basis will be rather low, but local areas (especially in or near the Sierra Nevada) could see some substantial precipitation. Early signs point to a pretty unstable airmass moving overhead later in the week (not hard to achieve with cold air aloft and a strong mid-May sun angle), so I would expect to see some strong thunderstorm activity once again at some point, at least in the Central Valley.

All in all, the current pattern is actually pretty typical for mid-late spring in this part of the world–which unfortunately means that there was no Miracle March, nor an Awesome April, and looking ahead there’s no real prospect that May will be particularly marvelous (to name a few of the alliterative names given to drought-alleviating surprises in years past). California’s average precipitation starts to decline pretty dramatically during the month of May, and the end of the climatological rainy season is nearly here. At this point in the year, there is little to no prospect of substantial drought relief before next October/November at the earliest, given California’s characteristic summer dry season.

Drought update: beware fire season 2015

I won’t dwell too much on this point, but just to reiterate: California’s exceptional, multi-year drought continues to intensify as long-term precipitation deficits grow ever-larger and record seasonal and annual-scale warmth persists. Recently, California enacted its first-ever mandatory statewide urban water restrictions–and certain human and natural systems are nearing critical tipping points. An emergency barrier is currently being constructed in the San Joaquin/Sacramento Delta to prevent the anticipated summertime intrusion of salt water from San Francisco Bay due to extremely low river flows, which would contaminate potable water being pumped to Southern California. Perhaps even more alarmingly, recent surveys by the US Forest Service, CALFIRE, and other agencies have discovered large swaths of dead or dying trees across parts of California, particularly coniferous trees in the Sierra Nevada. This remarkable increase in tree mortality–even among native species–is thought to result from a combination of primary drought stress (due to extremely warm temperatures, extremely low ground snow cover, and very low precipitation) and bark beetle infestation (which, itself, has likely been worsened by California’s unprecedented winter warmth over the past several years).

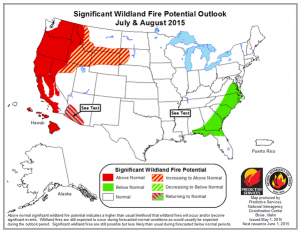

All of this means that much of California may be in for one heck of a fire season. Several fires last year–particularly the King Fire in El Dorado County, which at one point reportedly consumed as many as 60,000 acres in a six hour period–demonstrated that California’s forests are capable of truly explosive rates of spread as a result of the ongoing unprecedented drought conditions. After another dry and nearly snow-less winter, plus a worsening bark beetle infestation, the coming summer and autumn months may prove to be pretty nerve-wracking in California’s most fire-prone regions. The federal government’s official risk assessment for the coming fire season is stark, suggesting well above-normal risk of large wildfires all up and down the Pacific Coast. Many in the firefighting business will be the first to reiterate that the severity of any fire season ultimately depends a certain amount on luck: if we’re spared dry lightning events, prolonged heat waves, or powerful Santa Ana wind events before the next rainy season (and, too, if Californians are particularly careful, as the vast majority of wildfires are human-caused), it’s possible California will escape a destructive fire year. What is abundantly clear, however, is that the potential exists for a particularly severe fire season ahead.

Big changes afoot in the Pacific: El Niño has already arrived, and is rapidly intensifying

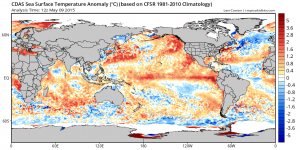

The meteorological community is currently abuzz with discussion of what now appears to be a rapidly intensifying El Niño event in the tropical Pacific Ocean. For the past 12-14 months, the North Pacific Basin has been quite warm overall, with warmth primarily being concentrated near the equator in the West Pacific and in the extratropics in the East Pacific (including along the West Coast of North America). There was much excited discussion last winter and early spring, as well, because many of the dynamical ocean-atmosphere models run by various international scientific institutions were suggesting the potential for strong El Niño conditions to develop by Winter 2014-2015.

Well, as most of us are aware by now, that didn’t happen, and the projections from winter/spring 2014 represent a considerable forecast failure on the part of the models typically used to make long-lead ENSO forecasts. Instead, the world bore witness to an El Niño event that barely reached the threshold for a marginal event–and, for the most part, didn’t exhibit the kind of ocean-atmosphere “coupling” we might typically expect. Persistent weakening of the easterly trade winds simply didn’t happen, and the incipient event just couldn’t sustain itself through the winter.

Now, a year later, we’re facing a situation that (at least superficially) resembles last year’s: it’s May, and there are compelling signs that a significant El Niño event is in the works. Like last year, a powerful oceanic Kelvin wave has propagated across the entire Pacific Basin, bringing very warm water and air temperatures to the coast of South America. Powerful typhoons in the tropical West Pacific are driving pulses of westerly winds near the equator, disrupting surface ocean currents and allowing warm ocean water to take the place of the typical Cold Tongue. Further, the dynamical models are once again suggesting the potential for a powerful El Niño event later in the summer and into the autumn/winter months.

How is the 2015 event different from last year’s “non-event?”

Can we expect this year’s event to fall apart like last year’s did? For a variety of reasons, I’d argue that it’s quite unlikely (though, as is ever the case in the coupled ocean-atmosphere system, not impossible). Why is this year different? Strictly speaking, it would be impossible for El Niño to fall apart as quickly as last year because it’s technically already here: various agencies have officially declared the arrival of weak El Niño conditions based on current observations.

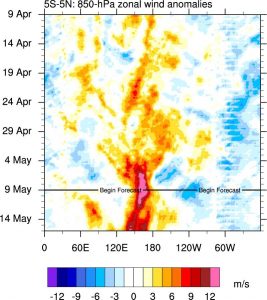

The most compelling difference between 2015 and 2014, however, is that the atmosphere finally appears to be responding strongly to warm ocean temperature anomalies. Easterly trade winds have slackened across the entire Pacific Basin, and a very strong westerly wind burst–on par with those which occurred in advance of the powerful 1997-1998 event–is currently ongoing near the Dateline. Further, observed SST anomalies in the far Eastern Pacific are now higher than those in the West Pacific, which means that the East-West anomaly difference is now greater than zero. El Niño is a tale of cascading, self-reinforcing feedbacks in the physical Earth system (which I discussed in a previous blog post on that topic)–and now, in 2015, it finally appears that these feedbacks are fully in play.

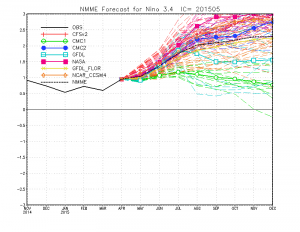

Another indicator of increased confidence in the forecast for 2015 is the eyebrow-raising amplitude of El Niño projections being generated by a wide range of ocean-atmosphere models. Several of these–including (but not limited to) the CFS and ECMWF models–are suggesting the strong potential for Niño 3.4 region SSTs peaking more than +3 degrees C during the coming autumn/winter. For reference, the highest values ever recorded were around +2.5C, and occurred during the strongest El Niño events on record in 1982-1983 and 1997-1998. In other words: a majority of the global atmosphere ocean models are currently suggesting the potential for an event rivaling the strongest event in the historical record.

It’s very important to reiterate, at this point, that just because the models are depicting a powerful El Niño later this year does not mean that such an event will actually come to pass. We need to look no further than last year for a stark illustration of that reality.

It’s also true that model forecasts through the month of May are still being generated in the midst of the so-called Spring Predictability Barrier–the period during which long-lead ENSO forecasts remain challenging due to the chaotic nature of the ocean-atmosphere system. I will note, though, that forecasts from May are notably better than those made in March or April, and that the projected peak strength of the current El Niño event has been monotonically rising with each month’s forecast so far in 2015 (while in 2014 the opposite was occurring).

It’s still too early to discuss the potential implications of a strong El Niño event for California (I already did that last year, and I’ll do it again in a month or so if conditions warrant). Strong El Niño events do tend to increase the potential for very wet winters through most of California (especially in the south)–but they certainly do not eliminate the possibility of very dry winters, even on a statewide basis. If an event as strong as is currently being depicted by some of the dynamical models does occur in 2015, it’s hard to imagine California experiencing another year of below-average precipitation. But that’s a very big “if,” and one thing is certain: we have a long, dry summer to come.

© 2015 WEATHER WEST