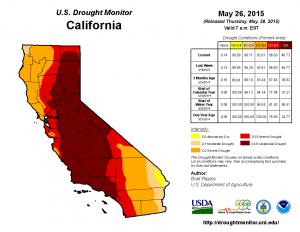

El Niño has arrived in the tropical Pacific, but what are the implications for California’s record-breaking drought?

Recent Weather Summary

California experienced yet another dry and record-warm winter in 2014-2015. The spring months, however, have been notably different in many places: May 2015 was the first cooler-than-average month in well over a year for the state as a whole.

In the Bay Area, in particular, May was a notably chilly month–by some metrics, even cooler than the balmily warm winter we just experienced. In a rather incredible climatological inversion, San Francisco recorded a May that was cooler than the months of January, February, March, AND April for the first time in recorded history. Some spots (like the San Diego area and parts of the Sierra Nevada along and east of the crest) have been fortunate enough to receive rather significant late-season precipitation over the past 6 weeks. Similar to April, though, May was a drier-than-average month overall in California. The long-term statewide precipitation deficit continues to increase.

Early signs of an El Niño teleconnection?

Clearly, a single month of slightly cooler-than-average temperatures and slightly less below-average precipitation hasn’t affected long-term drought conditions much, though it probably has kept high Sierra meadows green for a few extra weeks and may have slowed the start of wildfire season. But what has caused this relative reversal–from a record-warm winter to a relatively cool spring? It appears that a significant hemispheric-scale pattern change has finally started to develop over the past 2 months in response to strengthening tropical sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Pacific Ocean. These warm ocean temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific are associated with a strengthening (and much-discussed) El Niño event, are are expected to increase through the summer (more on that below). To date, increased tropical thunderstorm activity over the Central and East Pacific appears to have resulted in a chain reaction of weather anomalies across North America–including persistently cool (and occasionally unsettled) conditions over California.

Far more notably, a stronger-than-usual storm track–driven by an enhanced subtropical jet stream–has led to extraordinary, record-shattering precipitation and devastating flooding in Texas and across parts of the Great Plains in recent weeks. This kind of late-spring pattern is strongly reminiscent of we would expect to see during the early stages of a developing significant El Niño event, when atmospheric “teleconnections” (i.e. geographically remote effects of the warm tropical ocean) are not yet fully developed across the entire Pacific Basin/North America region. These teleconnections are usually better-defined during the winter months, though there are significant implications for both the Atlantic and East Pacific hurricane seasons (decreased and increased activity, respectively). For what it’s worth, current model forecasts are keying in on the potential for the continuation of an anomalously active late spring pattern over California through the first half of June, with an active mountain thunderstorm regime and perhaps even some convective showers/storms occasionally at lower elevations.

Given the strengthening El Niño event, do the drought-busting Texas floods suggest that California will be in for the same experience next winter? Not really–well, at least not directly. The kind of weather pattern that led to the Texas floods–persistent, moist deep convection (thunderstorms) with self-organizing characteristics (i.e. mesoscale convective complexes) aren’t really possible in California. We don’t have anywhere near the kind of warm, moist, and unstable conditions made possible in Texas by the proximity of the Gulf of Mexico, and large-scale atmospheric conditions near California are also generally unfavorable for this kind of event. But, as I’ll discuss below, significant El Niño events do have a meaningful influence on the risk of experiencing unusually wet conditions in California during our canonical winter “wet season.”

Strength matters: not all El Niño events have same effect in California, but watch out for the big ones.

There is currently quite a bit of excitement surrounding current expectations of a “significant” El Niño in 2015-2016, especially given California’s extraordinary multi-year drought and model forecasts suggesting the potential for a particularly strong El Niño event. I’ve seen a number of rather hyperbolic (and seemingly mutually exclusive!) news headlines suggesting, that either California is headed for an epic drought-ending flood disaster or that El Niño cannot (and will not) provide drought relief since such the vagaries of the tropical East Pacific are essentially irrelevant to precipitation here. As the astute reader might have guessed, neither of these headlines is particularly accurate–but the reality is far more interesting than the dichotomy above would suggest.

California, of course, receives the vast majority of precipitation during the cool season (the late fall through early spring months, or November through April). During most years, the months of December though March are most critical–and these are also the month during which most of California’s major floods have occurred. The fact that much of California has a well-defined, rarely-broken summer dry season means that a wet winter (and perhaps spring) will make or break the entire year–and also highlights the fact that any oceanic phenomenon (like El Niño) that might have the potential to influence precipitation on the annual scale would have to be acting during the cool season months. Thus, if we want to examine El Niño’s influence on California, it makes sense to focus on the core rainy season months of December through March. That’s not to say that El Niño can’t or won’t influence the risk of relatively rare summer rainfall events in the Golden State (I had a post focusing on this topic last year), but from the perspective of California drought relief, warm-season precipitation is highly unlikely to play a big role even during a strong El Niño year.

Weak El Niño events have highly variable effect; strong El Niño events usually increase winter precipitation

Note: for the purposes of this discussion, I have binned “weak,” “moderate,” “strong,” and “very strong” El Niño events according to Jan Null’s definitions, which rely on the Oceanic Niño Index.

El Niño has achieved broad popular recognition in California, largely a result of the substantial impacts associated with two exceptionally wet winters linked to the strongest El Niño events in the historical record (1982-1983 and 1997-1998). When discussed in the media, however, the conversation usually centers around the categorical question surrounding the effects of “El Niño” vs. “no El Niño.” As it turns out, this binary framing not a particularly useful way to structure the discussion of El Niño’s impacts in this part of the world.

Why is this the case? El Niño, on the whole, represents a weakening or reversal of the prevailing Walker Circulation, with typical east-to-west trade winds weakening or even becoming west-to-east winds (see this post from last year for more details). Because El Niño is defined so broadly, it actually encompasses a fairly wide range of atmospheric states–including a complete reversal of the direction of tropical wind patterns on seasonal timescales! It’s not all that surprising, then, that the atmospheric teleconnections associated with an El Niño event depend very much on the actual strength of the event. For weak events, the average atmospheric state over the Pacific Ocean isn’t all that well-defined, and historically California has experienced a very wide range of outcomes (including both very dry and very wet winters, along with everything in between).

In general, El Niño brings about a strengthening of the subtropical (low-latitude) branch of the jet stream, typically at the expense of the polar (mid-latitude) branch. California usually depends on undulations in the polar jet to bring periodic storminess in the winter months, though even during average winters the subtropical jet does occasionally make an appearance. During weak El Niño events, this effect is less profound, and the end result can often be relatively weak versions of both the subtropical and subpolar jet vying for influence over the East Pacific. The net effect can be quite variable; if California’s lucky, we see moist storms originating from both regions, but if we’re unlucky, we can largely miss out on storm systems taking both trajectories. If we composite the most recent weak El Niño episodes, the average effect in California actually appears to be a slight drying during the winter months–directly contrary to the El Niño mythology that pervades the Golden State.

However, things are a quite a bit different during a strong El Niño event. When East Pacific sea surface temperatures become sufficiently warm, large-scale atmospheric temperature differences between the tropics and the mid-latitudes are big enough to strengthen the subtropical jet quite substantially over the portion of the East Pacific that is most relevant for California wintertime precipitation. This enhanced subtropical jet can greatly enhance the strength of low-latitude storms west and even slightly south of California, and also makes it easier for such systems to tap into the rich tropical and subtropical atmospheric moisture reservoir that exists at lower latitudes. Additionally, storms during strong El Niño years have the potential to be more convectively unstable due to increased lower-atmospheric temperature and moisture, leading to an increased likelihood of intense localized downpours. In other words: a strong El Niño event tends to result in a jet stream structure that 1) steers more storms toward Southern California, 2) is favorable for stronger storms at a lower latitude in the East Pacific, and 3) affords pre-existing storms greater potential access to warm, moisture-rich airmasses.

Will El Niño end California’s extraordinary, multi-year drought during Winter 2015-2016?

Almost certainly not. Over the past four years of very low precipitation and record-shattering warmth, truly enormous water deficits have accumulated throughout California. On a statewide basis, the Golden State would need to see substantially more than an entire year’s worth of extra precipitation fall to eliminate the long-term deficit in a single year (in other words, a year with much greater than 200% of average). Since California’s all-time wettest years (typically associated with very strong El Niño events) have historically involved a doubling (200%) or less of annual precipitation, California would probably need to experience its wettest year on record (by a fairly wide margin) to erase ongoing deficits in a single year. While it’s not physically impossible, that would be a very tall order, indeed. And a winter like that would most likely bring a whole host of other problems (see below).

Since California’s all-time wettest years (typically associated with very strong El Niño events) have historically involved a doubling (200%) or less of annual precipitation, California would probably need to experience its wettest year on record (by a fairly wide margin) to erase ongoing deficits in a single year. While it’s not physically impossible, that would be a very tall order, indeed. And a winter like that would most likely bring a whole host of other problems (see below).

Could a strong or very strong El Niño in 2015-2016 substantially mitigate the California drought and/or lead to serious flooding?

Absolutely. If the developing El Niño event reaches a strong or very strong intensity and maintains its strength through winter 2015-2016, the odds of experiencing persistently wet conditions next winter will increase. The occurrence of frequent precipitation events during significant El Niño winters increases the probability that antecedent hydrological conditions will be moist if and when heavy precipitation events do occur, increasing the risk of flooding. Also, since the trajectory of Pacific storms during strong El Niño winters tends to be from a much lower (more southerly) latitude, air masses during rain events tend to be warmer and moister overall. This can have several effects, including higher snow lines and more rapid runoff, greater precipitation intensity overall, and an increased risk of deep moist convection (which can produce very high rainfall rates even in the absence of mountainous topography). It’s important to note that almost all of California’s major flood events result from landfalling “atmospheric rivers,” which tend to be more frequent (but not necessarily more intense) during El Niño years. Therefore, a major flood can easily occur during any winter, El Niño or not. Still, for upper-tier El Niño events, there is definitely an increased risk of above-average precipitation and flooding during the cool season.

Since strong El Niño events increase the likelihood of wet California winters, it does stand to reason that a strong El Niño in 2015-2016 could provide at least partial (and perhaps substantial) drought relief. A wet winter would most likely allow most of California’s major reservoirs to fill, though those who operate California’s dams and reservoirs are heavily constrained by flood control mandates. Surface soil moisture would increase, and drought-stressed forests and ecosystems would benefit substantially in the short term. Stress on urban water supplies would be reduced as demand decreases, and supply increases.

But even a tremendous amount of water falling from the sky won’t completely alleviate all of California’s drought impacts. And if much of this hypothetical precipitation were to fall as rain rather than snow in the Sierra Nevada, longer-term water storage wouldn’t be boosted nearly as much as it would otherwise. California is currently witnessing firsthand what happens during its first year in recorded history without a measurable springtime snowpack, and it’s becoming quite clear that warming temperatures aren’t very compatible with the snowmelt-dependent water storage infrastructure currently in place. The Pacific Ocean, on the whole, remains extraordinarily warm (even in regions geographically far removed from those used to define El Niño), and is expected to remain so for the foreseeable future. This means that even if heavy precipitation does return to California next winter, temperatures will likely remain well above the long-term average.

And just to reiterate a key point from above: we still don’t know for sure whether strong or very strong El Niño conditions will ultimately develop (nor whether they will persist until winter, when they are most relevant for California). Confidence is starting to increase in current projections, since we’re now emerging from the Spring Predictability Barrier and most dynamical models are still suggesting the potential for a powerful event. But when we concatenate all the various uncertainties discussed above, there’s still something of an open question regarding what happens in California next winter. At this point, it’s fair to state that the likelihood of experiencing a wetter-than-average winter (and, perhaps, flooding) is increasing, but simultaneously that the risk of the California drought continuing into 2016 is nearly 100%. Needless to say: it will probably be a very interesting year to come for weather and climate-watchers in the Golden State. Stay tuned!

© 2015 WEATHER WEST