North Bay firestorm of 2017

October 2017 will be a month not soon forgotten by many thousands of California residents living in the coastal counties just north of San Francisco. Late in the evening on October 8th, a cluster of extremely fast-moving, wind-driven wildfires roared across Sonoma, Napa, and Mendocino counties (as well as Butte County further north and east)–together burning well over 200,000 acres, destroying nearly 6,000 structures, and claiming the lives of at least 42 people.

Collectively, this wildfire outbreak has become both the deadliest and most destructive wildfire outbreak in California history, eclipsing even the 1991 Tunnel Fire in the Oakland Hills and the 2003 Cedar Fire in San Diego County. As of 10/19, most of these fires continued to burn, though containment has risen considerably and the risk of further risk to lives and property has diminished greatly.

Why were the October 8th fires so incredibly devastating, even in the context of California’s long history of large and frequent wildfires? Several key factors unfortunately converged in the North Bay during this extraordinary event. Perhaps most obvious: the development of very strong and bone-dry land to sea “Diablo Winds” over Napa and Sonoma Counties. Autumn is “offshore wind” season in California, as it’s the time of year when strong day-to-day variations in pressure over the Great Basin can result in steep pressure differentials between the elevated desert plateau and the coast. It’s the same process responsible for California’s so-called “Indian summers,” during which coastal regions often see their highest temperatures of the entire year due to the suppression of the prevalent summer marine layer. In its extreme form, however the “Diablo winds” (and its Southern California cousin, the “Santa Ana“) can result in extremely high fire risk–and can cause wildfires to advance faster than people can outrun them. In fact, this has been a common characteristic in all of California’s most destructive and deadliest wildfires: extremely rapid rates of spread are strongly associated with the occurrence of extremely dry and strong offshore winds in autumn.

Also contributing to the magnitude of the North Bay fire disaster was the proximity of fairly densely populated suburban neighborhoods to a large region of tinder-dry mixed forest and brush. Easterly winds in Sonoma County–which apparently gusted over 70mph along ridgetops and above 60mph even in the lower hills–drove the Tubbs Fire directly into northern portions of the city of Santa Rosa. It is this where the most lives were lost and most structures burned. Unusually, however, a significant portion of the burned area was apparently outside the designated “wildland-urban inferface” where most of California’s fire losses typically occur. How, exactly, did this wildfire manage to burn unchecked through multiple housing developments in the flatlands of Sonoma County (and, incredibly, jump over nearby Highway 101)? In addition to the very gusty Diablo winds, there have been a number of unconfirmed (but plausible) reports of “fire vortices” as the Tubbs Fire approached Santa Rosa. Such vortices act like fire-induced tornados, and while they have different mechanisms of formation than more traditional tornados produced by severe thunderstorms, they can ultimately be quite destructive and can cause a fire to “spot” ahead of itself a great distance. It’s possible that this phenomenon may partially explain why the Tubbs Fire became an essentially uncontrollable, localized urban firestorm. I’m sure there will be further investigation of this possibility in the weeks and months to come.

Finally, there is also the long-term climate context to consider. California just experienced its record-hottest summer, and the fire areas in particular suffered through one of the hottest autumn heatwaves on record back in early September. As the National Weather Service warned just hours before the fires broke out, vegetation moisture levels in the Bay Area had dropped to record-low values due to the extraordinary warmth over the past few months. This occurred despite a very wet winter across the Bay Area, which may have (somewhat counterintuitively) also contributed to increased fire risk by increasing the amount of dry grass and brush that grew during the spring months and ultimately dried out during the record heat this summer. Finally, as others have also pointed out, the legacy of California’s record-breaking multi-year drought is still being felt in California’s forested regions, where many trees remain drought-stressed and where tree mortality remains widespread. Thus, there is a strong argument to be made that the confluence of a wet winter (which enhanced the “flashy,” combustable fuels), the record-hot summer (which dried out vegetation to record levels), and the recent severe drought (which stressed trees to their limits) set the stage for the tragic events which have recently unfolded across Northern California.

Some good news: light rain today across hard-hit fire areas

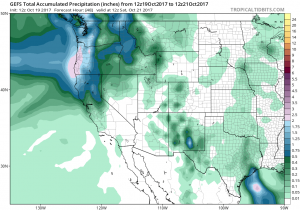

I do have some good news to report this afternoon: as I type this, a modest cold front is currently working its way down the Northern California coast, spreading light to moderate precipitation across the far northern reaches of the state. Later today and this evening, this front will bring some light precipitation as far south as the Bay Area–most likely including the hardest-hit fire region in the North Bay. While this precipitation will not be heavy, it will probably bring a “wetting rain” that will greatly reduce (if not extinguish) fire activity. This, combined with cooler temperatures and higher humidity in the wake of the front, will hopefully allow firefighters to wrap up containment on many of these fires by the weekend. Even very light precipitation, plus a shift in the winds, will also have another considerable benefit: air quality throughout the Bay Area (and across most of NorCal) will likely improve greatly.

However, fire season is not over yet: record heat, wind headed for SoCal

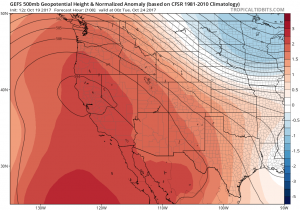

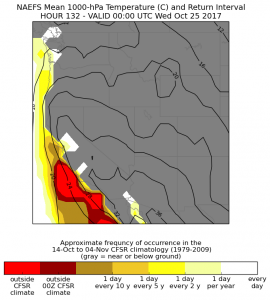

Following today’s NorCal respite, however, the overall news is not so great. This weekend, a very strong and seasonally anomalous ridge of high pressure is expected to build over California and the far eastern Pacific Ocean, bringing a dramatic increase in temperatures, along with plummeting humidity and even some offshore winds at times–especially across Southern California. In fact: there is now strong multi-model agreement that record high temperatures are quite likely to occur over nearly all of Southern California early next week. At the moment, it appears quite likely that daily temperature records for late October will be exceeded by a wide margin (i.e. by 3-5+ degrees in some spots). Downtown Los Angeles will probably experience its latest-in-the-calendar-year 100 degree reading on record next week, and could even approach 105. Even the beaches will be quite hot during this heat event–probably hotter, in fact, than during most of the significant inland heatwaves this summer. Early next week, there are also increasing signs that Santa Ana winds may develop–likely bringing critical fire weather risks for an extended period of time across much of Southern California

Temperatures across NorCal will not be nearly as hot as in SoCal during this event, though it will still be quite warm (80 and some 90s) for late October. Dry conditions will also prevail, along with occasionally breezy offshore winds. At the moment, there are no indications of especially strong winds in the northern part of the state over the next week, though this could change if any weak systems drop down the eastern side of the ridge over the Great Basin. The main message across California: the dry season is not over yet, despite the brief respite over the next 48 hours, and at the moment “fire season-ending” rains are still not on the horizon over most of the state. Stay tuned.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.