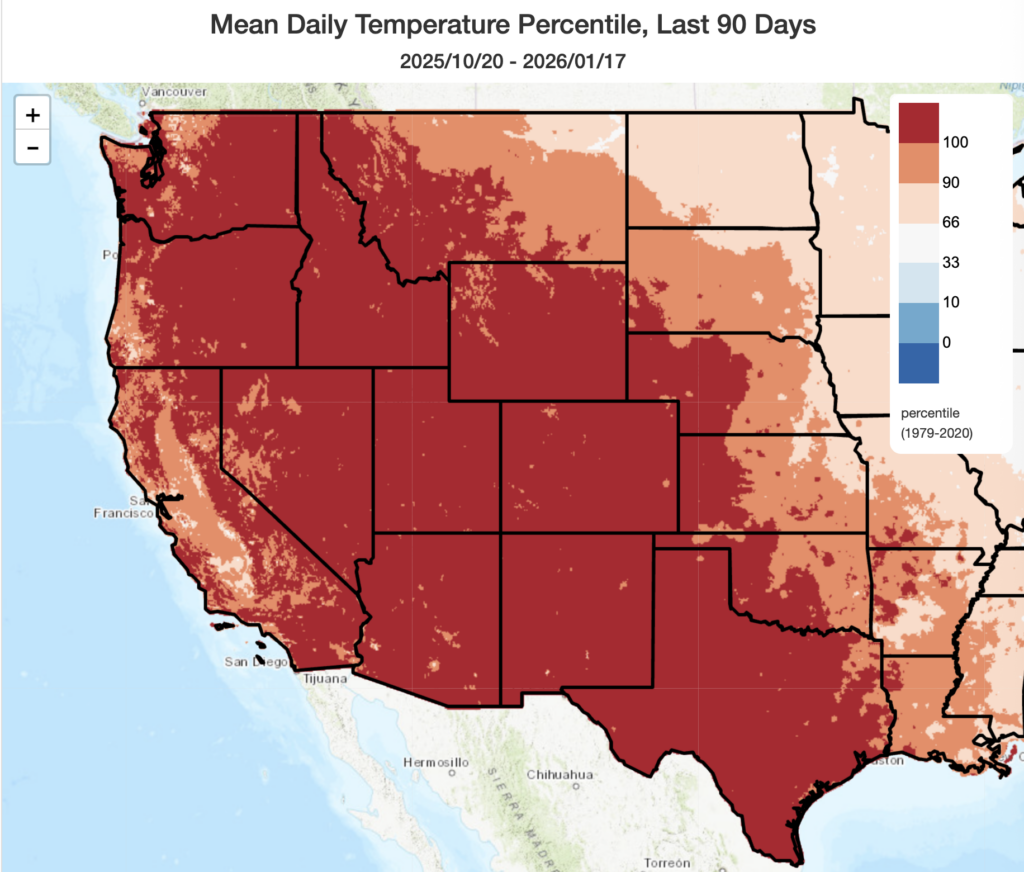

Yes, it’s still record warm out West and the snowpack really is that bad (outside of central/southern Sierra)

I’ll keep this part pretty short: it has been an absurdly warm winter thus far across nearly the entire American West, including most of California. One of the only exceptions has been CA’s Central Valley, where episodes of tule fog have kept conditions colder/damper for days at a stretch (but even here, episodes of record warmth interspersed within the foggy periods and lack of any major cold outbreaks have kept conditions among the top-5 warmest winters on record to date). This is all the more remarkable given that it has actually been quite a wet start to the season across much of the Pacific Northwest and Southern California; here, it has been warm and wet (as opposed to the more recently familiar warm and dry). But anomalous-to-record warmth remains the rule, and I don’t see that changing over the next couple of weeks

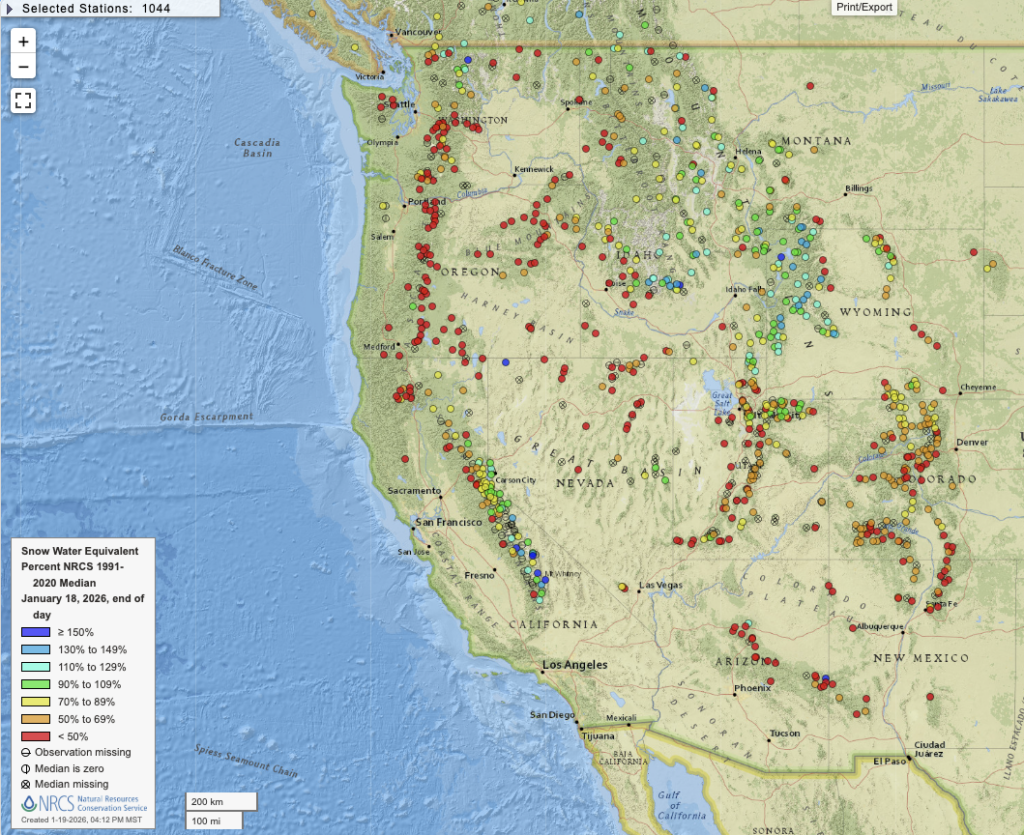

Snowpack conditions are, accordingly, terrible across most of the West, as a result; in fact, as of this writing, every single Western state has at least one snow water reporting site logging record low values for mid-January. Except for the Northern Rockies and Southern Sierra, where heavy precipitation in high elevation basins has outweighed the effects of record warmth, snowpack is far below average levels for the time of year and in fact is at singular record lows in numerous locations (most concentrated in Utah and Colorado, but widespread elsewhere and especially at lower elevations).

In California, some very high elevations sites have well above average snow water equivalent due to near-record precipitation earlier this season; other lower elevation observing sites in the very same region, however are once again nearing record lows. Higher elevation portions of the Tahoe Basin are doing okay for the moment (mostly 60-100% of the recent climate-warmed average), but lower elevations here too are suffering. And in the northern Sierra/southern Cascades and Shasta region, snowpack is near record low levels as well.

Generally speaking, given the warm and dry conditions over the next 10 days, and then perhaps wetter but still very warm conditions thereafter, I would expect further deterioration of the Western snowpack by Feb 1 and it’s possible that a majority of all observing sites will reach record low values by that point.

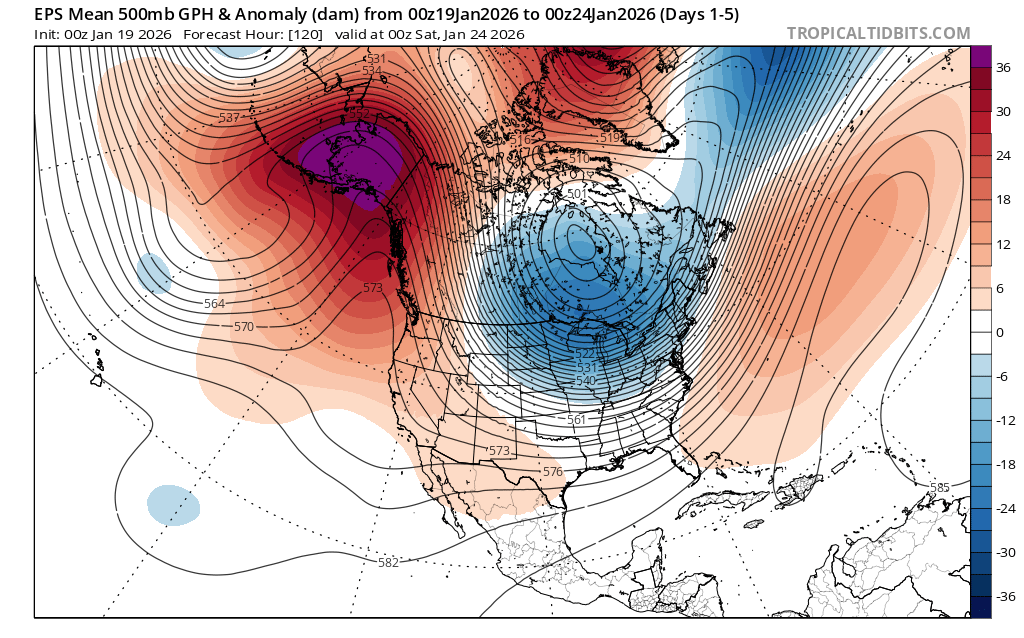

Highly amplified North American pattern leads to “Warm West/Cool East” dipole, with extreme thermal contrasts across CONUS

Despite the “lack of weather” across the West over the next week or so, these mostly warm and dry conditions will be generated by a very high amplitude pattern that may generate all sorts of weather-related chaos downstream. A strong and persistent ridge over or near the West Coast, paired with an equally persistent and deep trough over eastern North America, will lead to a period of extreme thermal contrasts from west to east over the continental U.S. (the so-called “Warm West/Cool East” dipole pattern). This pattern was a familiar feature during the 2013-2015 and 2018-2020 drought years–though this year, fortunately, California is presently drought-free (though the same cannot be said for the interior West and Colorado River basin). While persistent, it’s not (yet) “ridiculously” so. (And, in fact, the California pattern so far this Water Year has been characterized by very high intraseasonal variability, despite notable multi-week persistence in between wet and dry swings.)

This broader setup is a classic example of combined positive Tropical/Northern (+TNH) and negative Arctic Oscillation (-AO) patterns, which are known for generating locally extreme cold air outbreaks over eastern continental interiors and persistently warm conditions to the west of those Arctic surges. This is exactly how things will likely play out over the next 10 days over North America. Just how cold the eastern U.S. will get remains to be seen (likely quite cold, but I’m skeptical of truly record-breaking cold because the Arctic cold air reservoir is really depleted this year), but there could be some high-impact snow and ice storm events from the central U.S. to the Mid-Atlantic (possibly including some pretty southerly locations at times). Also notable is the quite anomalously warm airmass over much of the Arctic during this period as a tropospheric polar vortex is displaced southward over Canada. In fact, some portions of the west coast of Greenland will see temperatures that rise above freezing for an extended period (quite unusual forJanuary, and also something I…sincerely hope does not become of greater immediate geopolitical relevance in the coming days.)

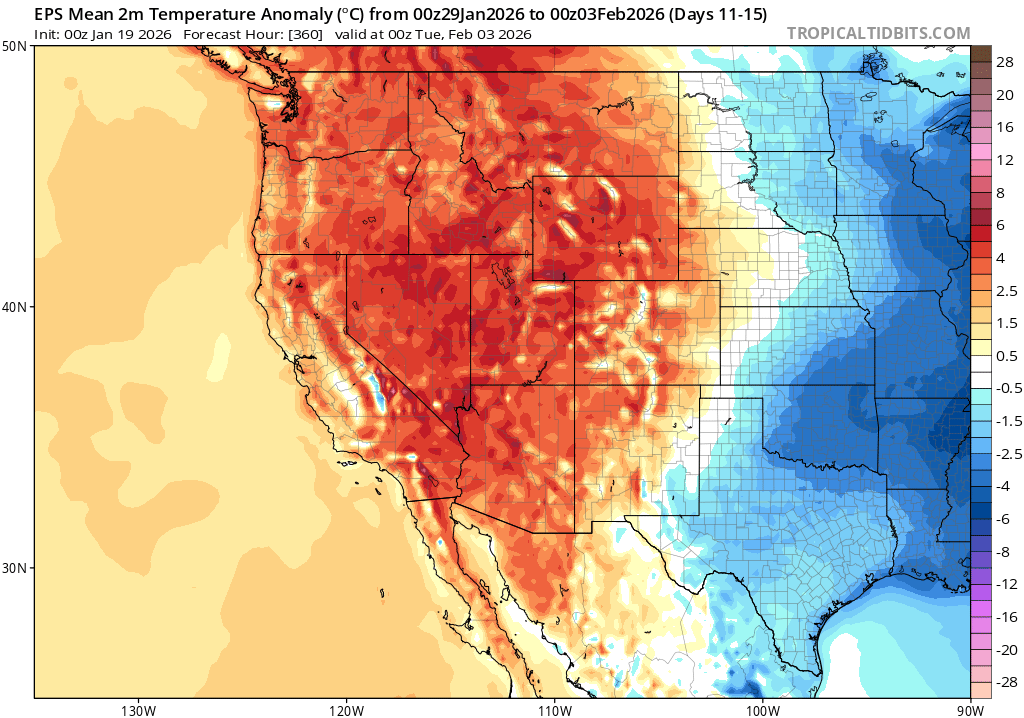

Mostly warm and dry across California next 10 days (except scattered SoCal showers later this week); possible late Jan pattern change, but with high uncertainty (and it would be wet and *warm*)

Across California, conditions will remain mostly warm and dry under the persistent West Coast ridge for the next 7-10 days. An exception will be in parts of SoCal, where a weak subtropical disturbance sneaking in under the ridge may bring some scattered showers later this week for a brief period. Some local fog may also continue in the Central Valley, though it will remain (as it has been recently) much less widespread than during the November episode. Elsewhere, relatively mild and locally near-record warmth can be expected to continue.

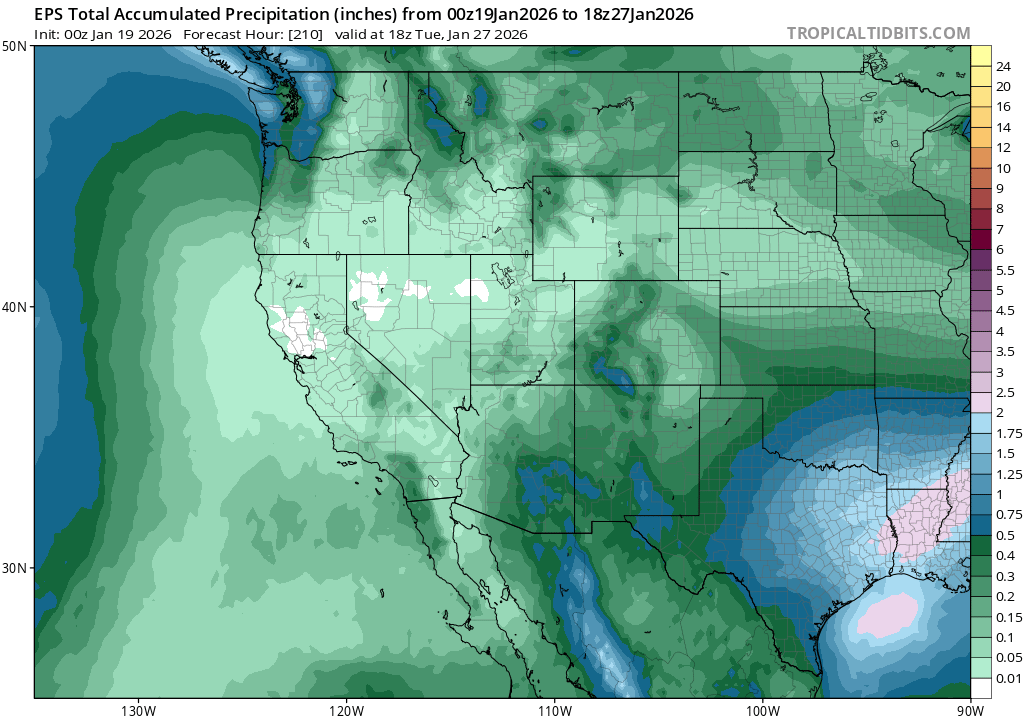

Looking ahead 10+ days, toward late Jan/early Feb, there are hints of a partial pattern shift–but it looks highly likely that anomalous warmth will persist regardless. A significant number of model ensemble members bring warm subtropical rains back to California and the West Coast during this period, which would end the dry spell but be unlikely to improve mountain snowpack. There is high uncertainty during this period, as stronger Pacific storms will remain deflected away from California due to the broad ridge but some very moist subtropical moisture plumes could nonetheless drop significant rainfall during this period. Rainfall during this period could range from zero to rather heavy, depending on where these plumes end up being directed. So I’m confident in the “much warmer than average” part, but much less so on the precipitation front beyond days 9-10.

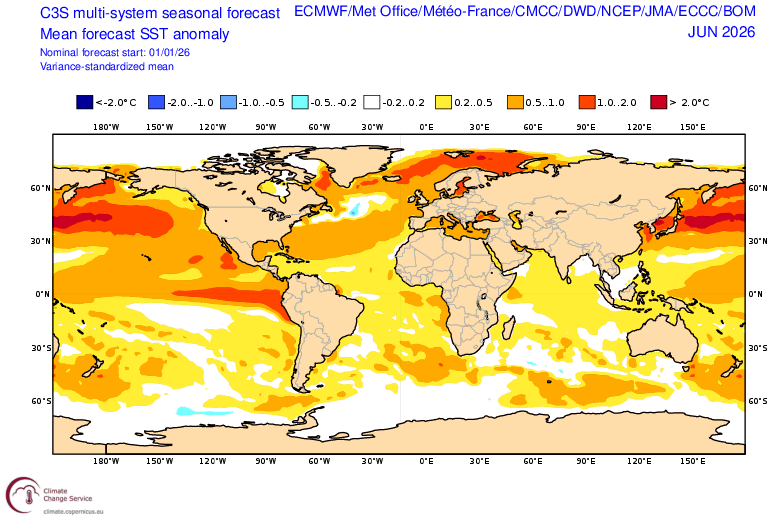

Growing indications of rapid transition toward El Niño conditions; significant event possible by summer

All signs appear to be pointing toward the rapid development of El Niño conditions in the tropical Pacific by spring or early summer. In fact, the latest “superensemble” blend update from last week suggests very high confidence in this outcome, with a slight chance of rather strong El Niño conditions in place already by June. This is a very aggressive forecast–unusually so far so early in winter. And it is supported by recent observational trends, with multiple persistent/strong westerly wind bursts now ongoing in the tropical western Pacific and a substantial oceanic subsurface warm water mass moving eastward. I’ll be watching this closely in the coming weeks, as this could begin to affect California and western weather as soon as April or May.

YouTube livestream on Wed, Jan 21 at 12 Noon Pacific Time (and please consider subscribing to the channel!)

I’ll host my next live, virtual, and interactive “weather and climate office hour” on YouTube this Wednesday at noon Pacific Time. I’ll be discussing the causes and potential implications of the record low Western U.S. snowpack, and also the developing transition toward El Niño conditions in the tropical Pacific.

If you enjoy this blog, or my short-form social media posts across multiple platforms, I’d strongly encourage you to subscribe to the Weather West YouTube channel! Even if you’re unable to join live, my livestreams are always recorded and archived; they typically become available immediately after the stream ends, with higher resolution versions becoming available shortly thereafter. As a bonus, if you subscribe and turn notifications on, you’ll be automatically informed whenever I schedule “pop-up” live events on short notice!