Widespread lightning event last week wetter than expected, though still sparked a few major fires

The best news to come out of last week’s widespread lightning event in NorCal (and, somewhat unexpectedly, in coastal SoCal as well) is that the thunderstorms ultimately were a bit wetter than initially expected. Thousands of lightning strikes did occur, and there were numerous new fire ignitions throughout NorCal. But brief downpours helped keep *most* of those initial starts at bay for long enough for firefighting crews to address them. “Holdover” fires have been popping up all week in the more densely forested parts of NorCal, but that risk has probably diminished to near zero at this point. The major exception to this pretty good outcome (all things considered) is the southern Sierra Nevada, where two new fires/complexes (the Windy Fire and the KNP Complex) are now burning intensely in drought-stricken forest. These fires are “filling in the gaps” between a number of major, high intensity fires in this region over the past few years–and they do have considerable room to grow to both the west and east (depending on wind direction in the coming days/weeks).

Some good news: soaking North Coast rain this weekend, and lighter showers somewhat farther south

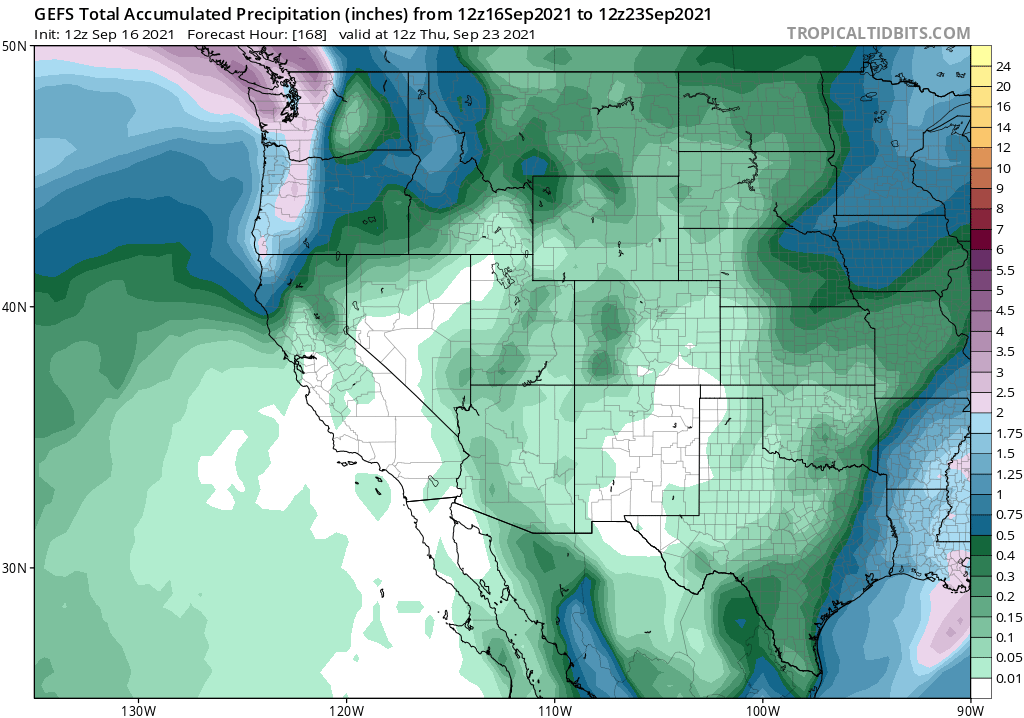

I’m happy to report a pretty high chance of significant rainfall (without lightning!) this weekend along the immediate North Coast (Eureka-Arcata corridor will likely get a nice soaking) as a fairly strong early season atmospheric river makes landfall across the Pacific Northwest. As expected, recent model ensemble predictions have backed off somewhat on the amount and southern extent of the precipitation in California. The northern quarter of NorCal, including the interior, is still likely to see some wetting rains (0.1-0.3 inches), and some sprinkles/light showers are likely as far south as about the I-80 corridor. There could be some wet windshields, and maybe even a puddle or two, as far south as the North Bay on Saturday. Some of the large/active fires in the northern quarter of CA will also see reduced activity in the wake of this modest moisture. But away from far NorCal, this will be a transient and glancing blow. Unlike in the PacNW (OR and WA), where “fire season ending” precipitation is likely this weekend, these rainfall amounts won’t greatly influence fire risk in California for more than a couple of days (except along the North Coast, where conditions will be pretty damp for a while). Still, it’ll be nice to have at least a brief period of higher humidity, clouds, lower temperatures, and improved air quality in most areas.

Some not so good news: winds will increase fire weather threat from Fri into early next week

The same frontal system and trough expected to bring some needed rain to the PacNW and far NorCal will also generate fairly strong onshore flow across interior NorCal and central CA, including the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada. Strong w/sw winds, combined with extremely dry vegetation and existing fires (esp. in the southern Sierra), will lead to increasing fire weather concerns as early as Friday and continuing this weekend. Then, on the backside of the trough, some weak to moderate *offshore* winds could start pushing fires in the opposite direction. I don’t currently think the Mon offshore wind event will be especially strong, however.

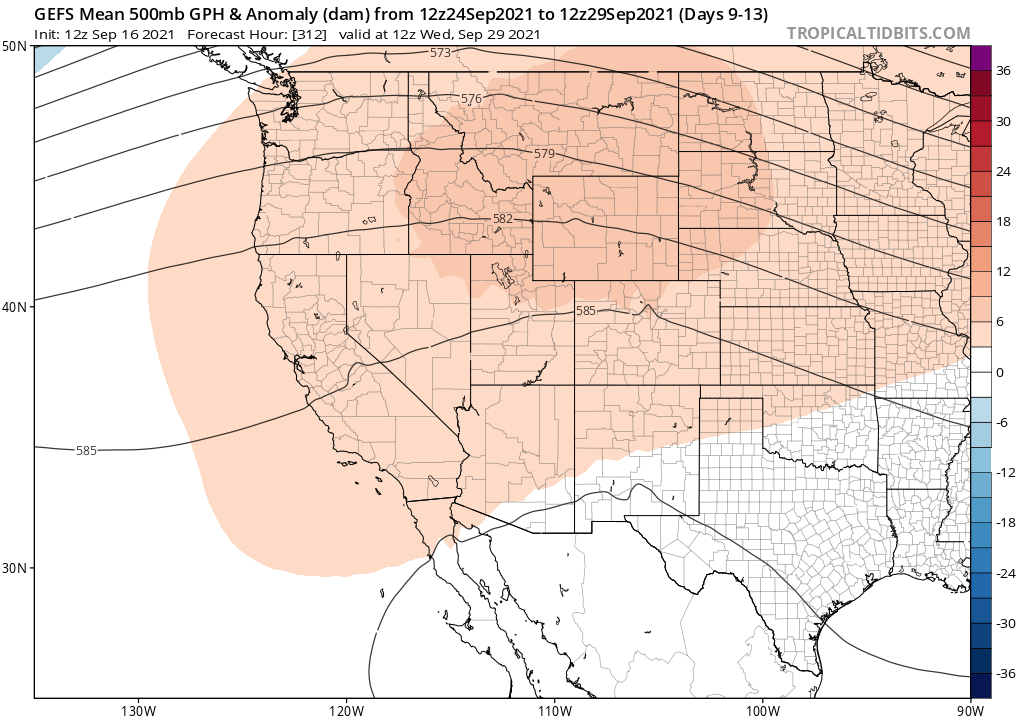

Conditions appear likely to dry out and warm up thereafter, although there has been quite a bit of inter-model variability as we head toward late Sept. There are hints of a stronger offshore wind event later next week, but it’s really too early to tell. One thing that is clear is that model ensembles are pointing toward warmer-than-average conditions returning essentially statewide by the end of the month, and likely continuing for a while thereafter.

Some thoughts on the “rainy season” to come: La Niña, philosophy of prediction, & other things

The California weather-aware among us have a variety of (sometimes contradictory) perspectives on seasonal precipitation predictions. One thing that is clear is that they’re far from perfect–and that’s likely an understatement. Historically, such season predictions for precipitation don’t have a stellar track record–and have produced some pretty conspicuous predictive misses in recent years (2015-2016, for example).

All of that said, these predictions are also not quite a useless as some have been led to believe. Viewed in the right context, they can still be useful–and these predictions have actually gotten measurably better over time. (The seasonal predictions, unfortunately, nailed the 2020-2021 outlook–calling for a very dry autumn, winter, and spring in California.)

How are seasonal predictions made? Well, the process is pretty similar to weather predictions–but the ultimate goal is somewhat different, as are the most relevant physical variables. When it comes to weather predictions (0 to 10 or 15 days in the future), the atmospheric initial conditions (i.e., what does the 3D structure of the atmosphere look like, in terms of wind/pressure/humidity/temperature/etc. at the exact moment when the model starts to run forward in time) are of paramount importance. But on longer timescales, especially when looking forward weeks to months, initial conditions in the rapidly-evolving atmosphere become less important and the initial state of more slowly-evolving components of the Earth system (like ocean temperatures, land surface soil moisture, extent of Arctic sea ice) become dominant. (And while that isn’t the focus of this blog post, it’s worth mentioning that initial conditions become even less important when it comes to climate projections years to decades in the future. Here, the question shifts from being an “initial condition problem” to a “boundary value problem,” in which external factors like atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations are most important).

The goal of a seasonal prediction is not to provide a specific forecast (i.e., “it will rain on December 10th in San Francisco). Instead, the aim is to offer probabilistic insights into the most likely state of the system several months in advance (“there is a 70% chance of below-average precipitation in central California during December through February”). As such, it’s impossible to evaluate the accuracy or “skill” of a seasonal prediction on the basis of a single season, or even a small number of seasons. Scientists consider many years or decades of seasonal predictions to assess skill–and that’s the basis for continuing to discuss these kinds of outlooks despite some high-profile “failures” in recent years.

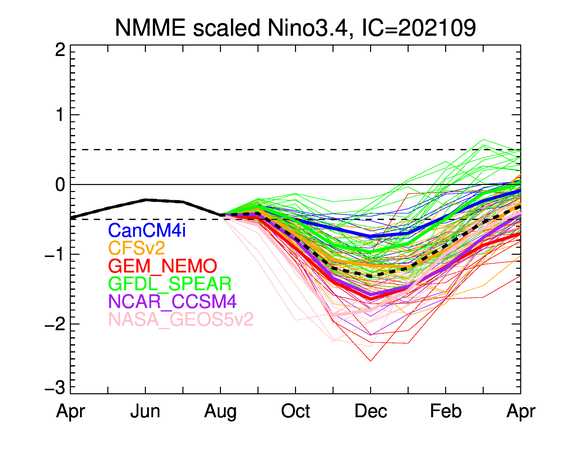

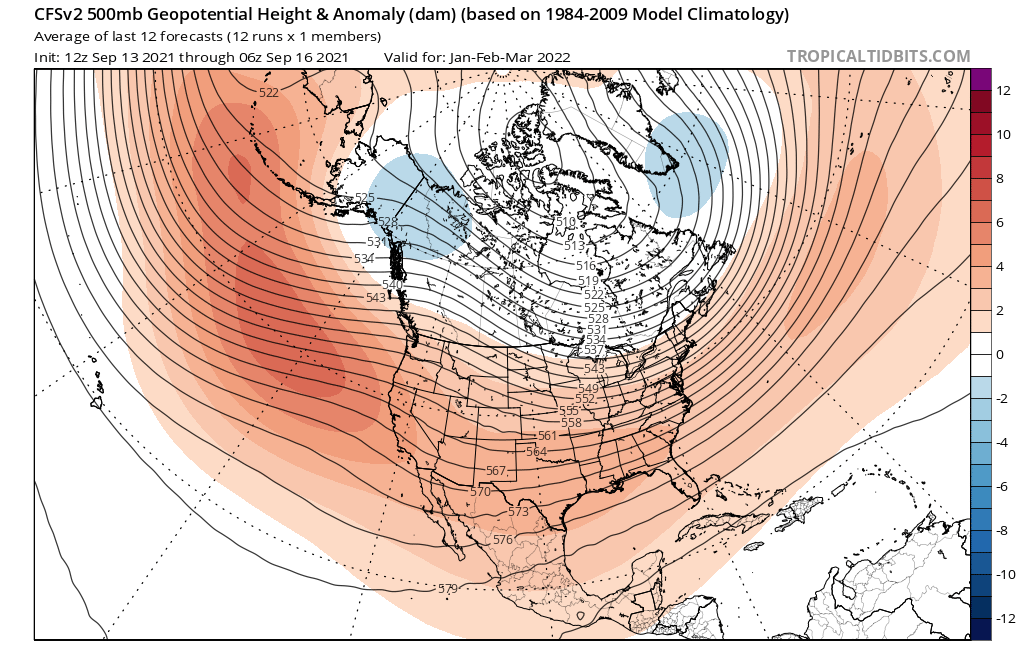

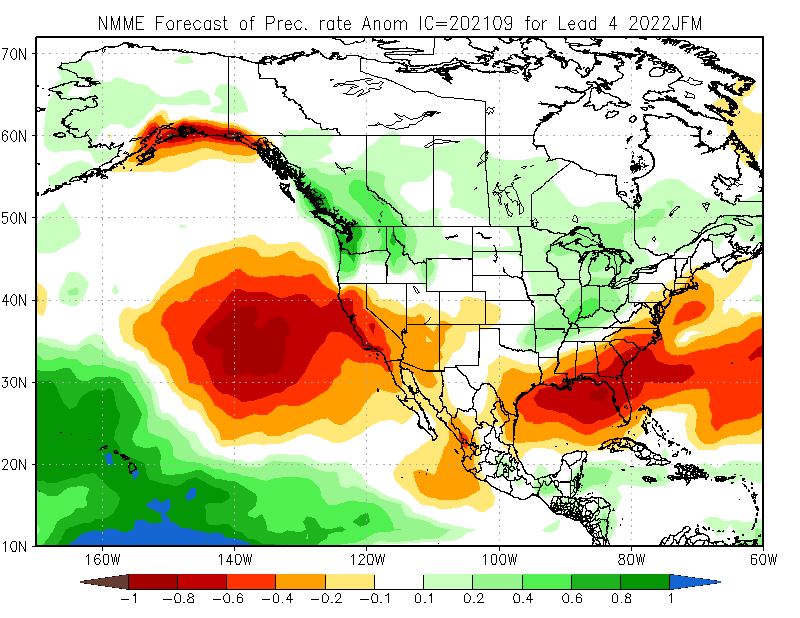

So, how are things looking for 2021-2022? With all the caveats above, especially that these are *probabilistic* (not deterministic) outlooks: not so good. Nearly all seasonal models are pointing toward the re-strengthening of La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean, plus a continued presence of unusually warm ocean waters in the tropical West Pacific. As we showed in some peer-reviewed work a few years back (and previously discussed in this blog post), that’s a recipe for persistent high pressure/ridging over the northeastern Pacific during the California “wet season”–and thus increases the odds of a drier-than-usual season to come.

What do the seasonal models say? Well, they appear to be making a prediction that’s very consistent with what I would estimate from our own prior work–they are suggesting fairly high odds of yet another dry winter across most or all of California (with confidence highest across the southern 2/3 of the state). Interestingly, these same models are suggesting that following a dry autumn (except perhaps along the North Coast), December could potentially be a pretty wet month in parts of CA! But thereafter, there seems to be a fairly strong indication that multi-month ridging will take hold and could keep California much drier than average during the peak rainy season months of January through March (and into the spring, as well, although that’s more speculative at this early juncture).

Does all of this mean that a very dry winter is guaranteed? No, absolutely not. And even a “modestly dry” winter could still be a lot wetter than last year’s near-shutout in some parts of NorCal. But this kind of seasonal outlook is nevertheless concerning due to the extremity of the ongoing drought in NorCal and recent reports that some (small to medium sized) water districts are already considering emergency measures to keep the taps from running dry next year. California’s ecosystems are already extremely drought stressed, and another dry winter could bring impacts substantially exceeding either the 2013-2016 drought or the 1976-1977 drought. And temperatures have continued to warm in California since both of those droughts–further amplifying rates of water loss from the landscape and compounding potential consequences. I sincerely hope California gets lucky this winter and ultimately sees a solid rain/snow year (and this is still possible, despite current seasonal predictions). But from a risk management perspective, it’s long past time to start considering what mitigation measures might be required if drought severity substantially exceeds that of 2013-2016 or 1976-1977.

Obviously, I’ll keep tracking these developments in the coming months. Stay tuned.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.