Despite unsettled start to month, no “March Miracle”

The first half of March was actually a reasonably active weather period for much of California, with several cold cut-off lows bringing bouts of showery and unstable conditions. Widespread (if brief) bursts of small hail brought unusual wintry coatings to many areas, and quite a few folks witnessed some thunderstorm activity. Precipitation, while widespread, did not ultimately result in heavy accumulations in most places. Thus, despite these widespread March showers, precipitation totals for the month of March are on track to end up below average across most of the state. Were March the only dry month this year, that wouldn’t be much of a problem–but in a year when many folks were hoping for a drought-busting March Miracle, this was a rather disappointing showing.

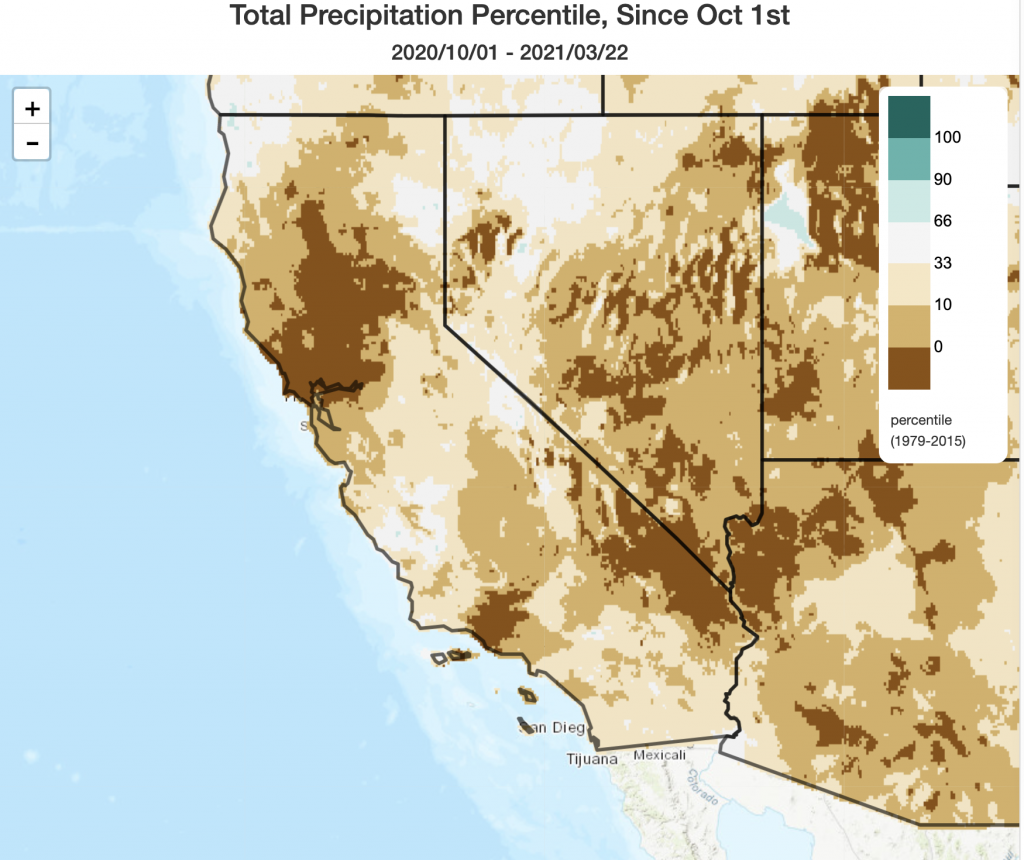

The 2020-2021 “rainy season” to date has, in fact, turned out to be exceptionally dry across portions of California. I think this probably slipped in under the radar, given everything else that has transpired in the world over the past few months, but some parts of northern California (including the SF North Bay, Mendocino County, and much of the central/northern Sacramento Valley) are currently experiencing their driest season since the 1976-1977 drought (and a few places are running behind even that infamous season). This is doubly concerning as these same regions experienced a top-5 driest winter on record just last year–so this is now year two of exceptionally low precipitation in these areas. All of this is amplified by the prolonged periods of record high temperatures and drying offshore winds last year–both of which reduced water availability beyond what would be expected from precipitation deficits alone.

There are a few exceptions to the “exceptionally dry” categorization: patches of the Central Coast and central San Joaquin Valley benefited greatly from the powerful atmospheric river event earlier this winter and are merely 20-30% behind average, and some small areas in far southern coastal CA benefited from the southern-track cut-offs in Feb-Mar. Sierra Nevada snowpack is not exactly a bright spot, but at 65% of average for the calendar date it’s actually less dismal than overall precipitation deficits would suggest (thanks, in large part, to the cold AR event earlier this winter). But in general, California is in pretty bad shape water-wise heading into spring 2021–and I would expect the pre-existing drought to deepen considerably. Expect to hear much more about this in the coming weeks.

Continued dry conditions into April

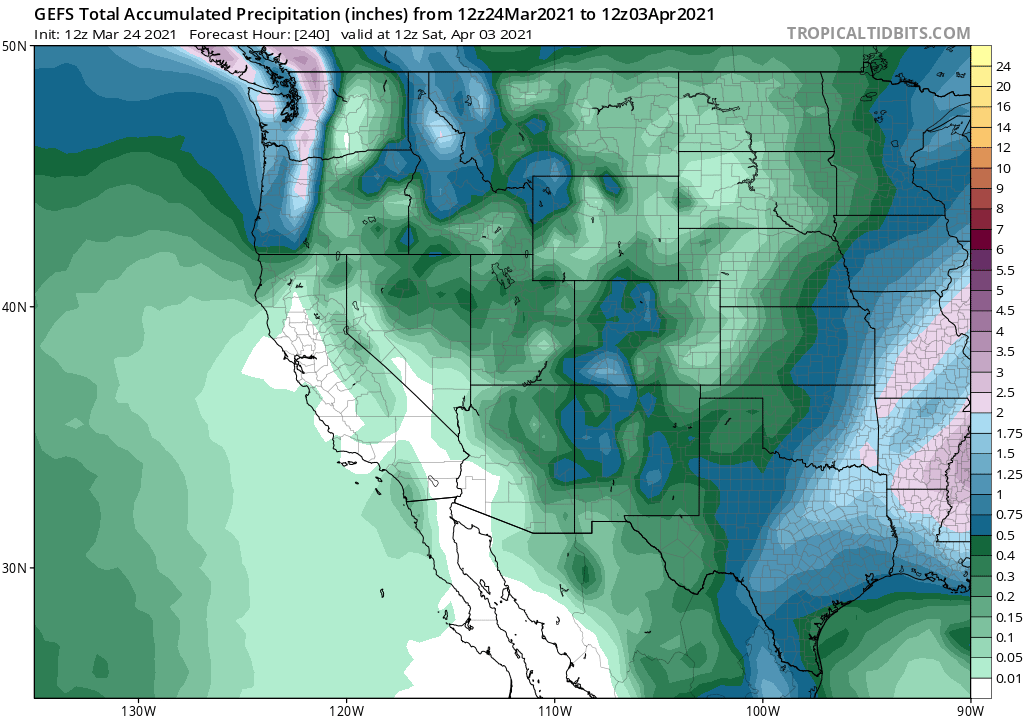

Unfortunately, there’s really just not much precipitation on the horizon to report. Continued dry conditions are predicted by all available modeling ensembles for the next 10-14 days, which brings us to early April. There are also indications that currently near-average temperatures will rise well above average during the first week in April. It’s a bit early to have major heatwaves, and currently I don’t foresee anything extreme on the immediate horizon, but temperatures will likely feel increasingly spring-like.

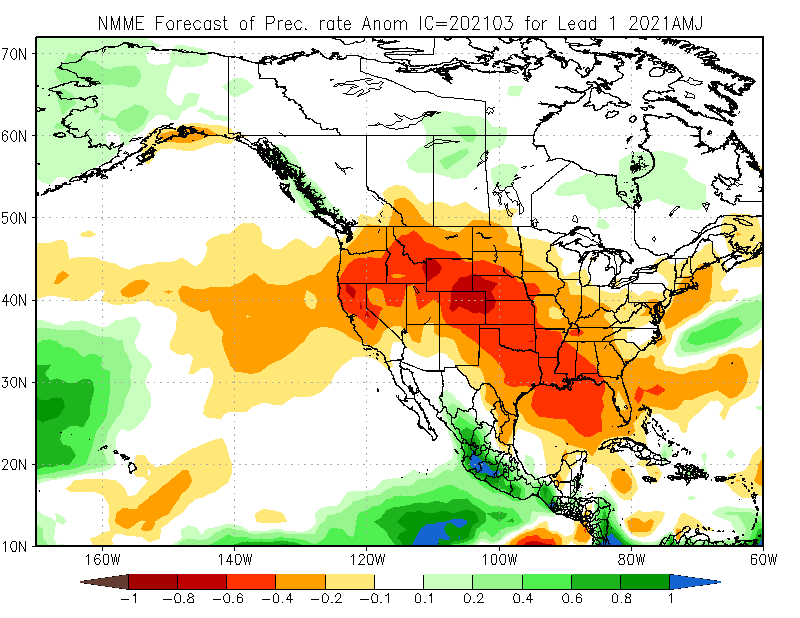

In the slightly longer term, there also isn’t a great deal of good news to report regarding sub-seasonal predictions for spring. There continues to be strong multi-model agreement regarding below-average precipitation across CA (and much of the American West, in fact) during the April-June period. I’m increasingly concerned that the widespread severe dryness and intensifying long-term drought conditions will lead to another very severe wildfire season across a broad portion of the West in 2021. It is possible that some of the extensive areas that burned over the past 1-2 years may see a local reprieve this year given the limited re-growth of vegetation that has occurred in the immediate vicinity of recent fire areas amid the drought, but I’ll admit that’s a pretty modest silver lining.

The Ridiculously Resilient Ridge has returned…again…in 2020/2021

In the past, I’ve cautioned that the existence of a “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge”-like feature is really only discernible in retrospect, when we can be certain that there was actually multi-month persistence of anomalously high mid-tropospheric pressure (geopotential heights). Well, I just looked back at the dismal 2020-2021 season, and…it’s back. The November-March 2020-2021 (to date) North Pacific geopotential height anomalies are plotted (using the ever-useful ESRL plotter) in the map below, and the anomalous ridge signal west of California clearly stands out.

Interestingly, this particular iteration of the Triple R is more reminiscent of the original RRR in its very early days–all the way back in 2013. In 2020-2021, the ridge was centered over 1000km west of California in a position that allowed for a large number of cold and dry systems to slide southward along or just east of the West Coast. These storms brought cold air at times and lots of wind (remember all those cool-season offshore wind events recently?), but in most instances not a lot of precipitation. So the sensible weather this year has been quite different than in other Triple R years (like, say, 2013-2014 or 2014-2015) when the ridge was essentially aligned with the West Coast. In those years, conditions were very dry and also very warm. This year, conditions have been very dry (and windy) but considerably less warm. But from a drought perspective, a ridge anywhere near or west of California during the rainy season tends to be very problematic–it simply doesn’t allow for enough rain or snow to fall.

It’s worth noting that this persistent North Pacific ridging and subsequently very dry California winter was well predicted by the seasonal models this year (which is not always the case!). It’s a predictive success that will unfortunately have serious implications for the deepening drought across California and the broader West. In past blog posts, as well as in my own peer-reviewed scientific research, I’ve extensively explored the context and causes of seasonally-persistent and drought-inducing high pressure systems over the North Pacific (check out the overview blog post, or navigate directly to the relevant papers). This year’s ridging was most likely a response (primarily) to relatively strong La Nina conditions in the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean, as well as anomalous warmth in the tropical West Pacific (consistent with our prior work). Other factors are likely at play, too, but those are harder to tease out in a year-to-year sense and remain the subject of ongoing research.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.