Extraordinary, historically unprecedented wildfire conditions across central & northern CA and OR

Even in a year that has already featured many well-justified superlatives, it is becoming genuinely difficult to articulate just how severe the ongoing wildfire emergency has become in California. The numbers were already shocking back during the August lightning bust and subsequent wildfire siege, but those August numbers now look modest in comparison to today’s astonishing statistics.

Around 3.5 million acres have burned so far in California in 2020. That’s around 3.5% of the entire land area of the state, and is approaching *double* the previous record for the greatest acreage burned during a single year in the modern record (~1.9 million acres in 2018). The August Complex, which began initially as a series of lightning fires back in August but have now merged into a single contiguous fire extending many miles in every direction, is now approaching ~900,000 acres in size and has burned most of the Mendocino National Forest. This is now California largest fire on record by a ridiculous margin–it’s essentially double the previous record, previously set just two years ago in 2018. Given the minimal containment on this fire and continued adverse fire weather conditions expected in the coming days, I would expect the August Complex to become California’s first true modern “megafire” in the coming days–a single contiguous event burning over 1 million acres.

The human toll has been rising, too. The death toll from the California and Oregon fires continues to rise into the dozens, and the news coming out of the Bear Fire/North Complex is particularly sobering. Multiple small towns and neighborhoods in Butte County were overrun by the fire in the middle of the night as it made an astonishing ~200,000 acre run in less than 24 hours–creating conditions eerily similar to that of the Camp Fire back in 2018. The only saving grace in this instance is that there were no large towns in the direct path, but the devastation in north and east of Oroville is immense, and as yet largely untold. Heroic rescues, during which hundreds of people have been extricated under extremely dire circumstances, have been commonplace in recent days–including a mobilization of the California Air National Guard for daring midnight helicopter evacuations. Thousands of structures have burned just in California so far this season, and the toll continues to climb.

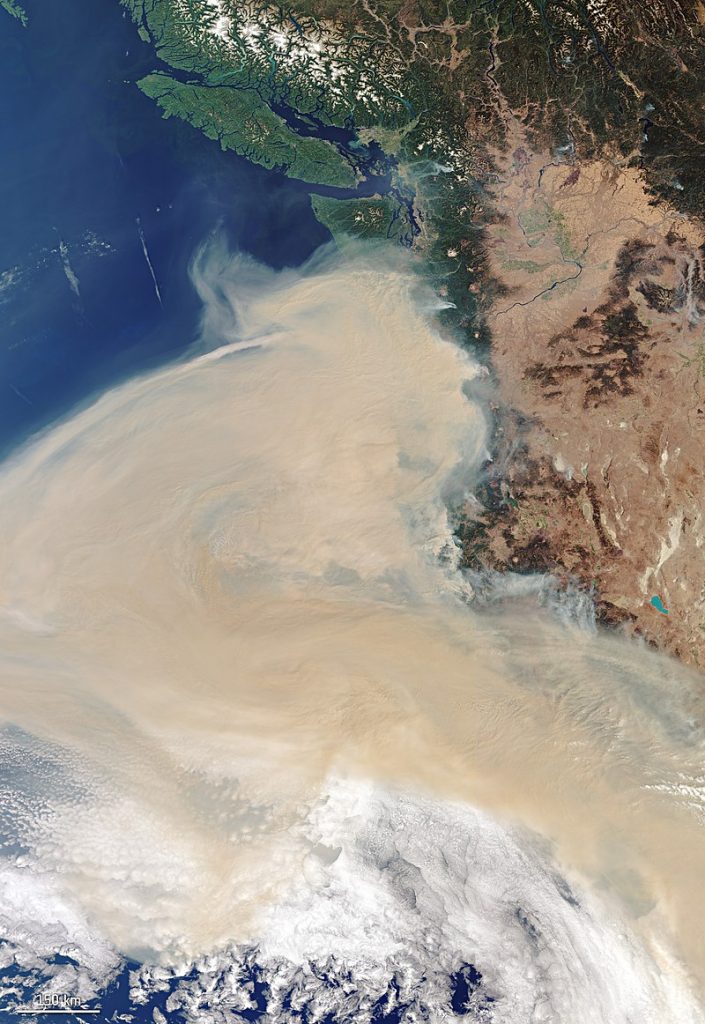

Widespread “smokestorm” conditions persist West Coast-wide

Then, on top of all of that: the smoke. An extremely large volume of dense, choking smoke has been generated by these numerous extreme large wildfires across California, Oregon, and Washington–leading to “smokestorm” conditions of historic proportions extending all the way from the Mexican to Canadian border (and even farther, at times). Air quality has ranged from “poor” to “extremely hazardous” across California for many consecutive days–making it difficult to even open windows, let alone spend time outside.

Even more dramatic, though, was the vertical depth and density of these smoke plumes last week. At one point, multiple fires were generating explosive pyrocumulonimbus (fire thunderstorm) clouds that injected smoke all the way toward the top of the troposphere and even briefly into the stratosphere. The depth of this smoke column–which extended from the surface to nearly 30,000 feet–was sufficient to essentially block out the sun even at midday in some regions, leading to surreal and Bladerunner-esque scenes throughout Northern California. Aside from dramatically altering everyday life, these dense smoke plumes have also radically altered local meteorology–bringing temperatures 10-20 degrees cooler than the ambient airmass would support as solar radiation was largely unable to penetrate the plumes.

How did we get here? Record heat (x2) immediately followed by unusually early offshore wind event

California experienced a searing, record-breaking, and long duration heatwave in mid-August (coincident with the dry lightning that provided the initial spark that ignited many of the fires still burning). Then over Labor Day weekend, a shorter but even more intense heatwave arrived–bringing all-time (any month) record temperatures to portions of California, especially in the south. LA County saw its highest temperature in recorded history (121F), and San Luis Obispo reached 120F–possibly setting a new record in the Americas for the hottest temperature so close to an oceanic coast. In the end, August 2020 turned out to be the hottest August on record in California.

And then, across the Pacific Northwest, the offshore winds arrived. An unusually powerful early season storm over the interior west generated an extreme surface pressure differential, which bring once-in-a-generation easterly winds to Oregon as well as strong winds to the fire areas in NoCal. These extreme winds in Oregon were themselves the cause of some of the numerous, extremely large fires now burning–numerous trees and power lines were knocked down. If you’re interested in the genuinely fascinating series of meteorological events leading up to the historic post-Labor Day wind and fire event, I’d encourage you to click and read the full Twitter thread below.

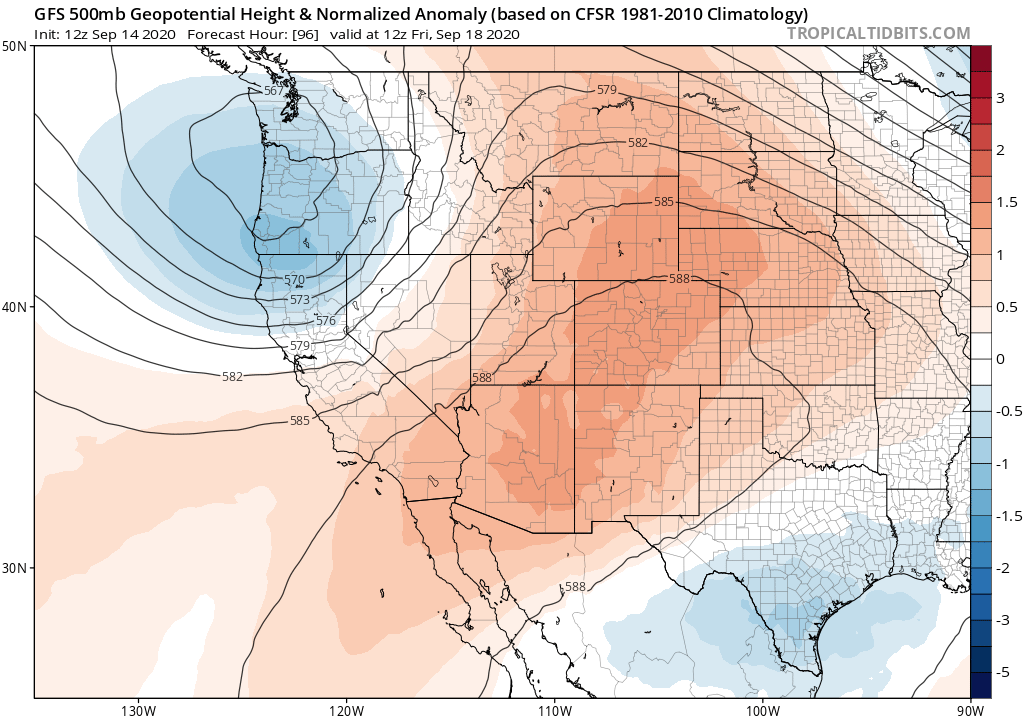

Pattern shift will bring smoke relief, but winds may fan flames

The upcoming pattern shift is a classic “good news, bad news” situation. I’ll start with the good: increasingly strong and vertically deep southwesterly winds over California and the PacNW will slowly start to scour out the smoke and hazardous air quality that has plagued the region for days on end. These winds won’t bring instant relief–there is actually still quite a lot of smoke out over the Pacific to blow inland first–but I do expect surface air quality to improve gradually but steadily over the next few days. Vertical mixing will also improve–so even if there is elevated smoke remaining higher in the atmosphere, it might become more reasonable to open windows and perform outdoor activities as smoke gets less concentrated near the surface.

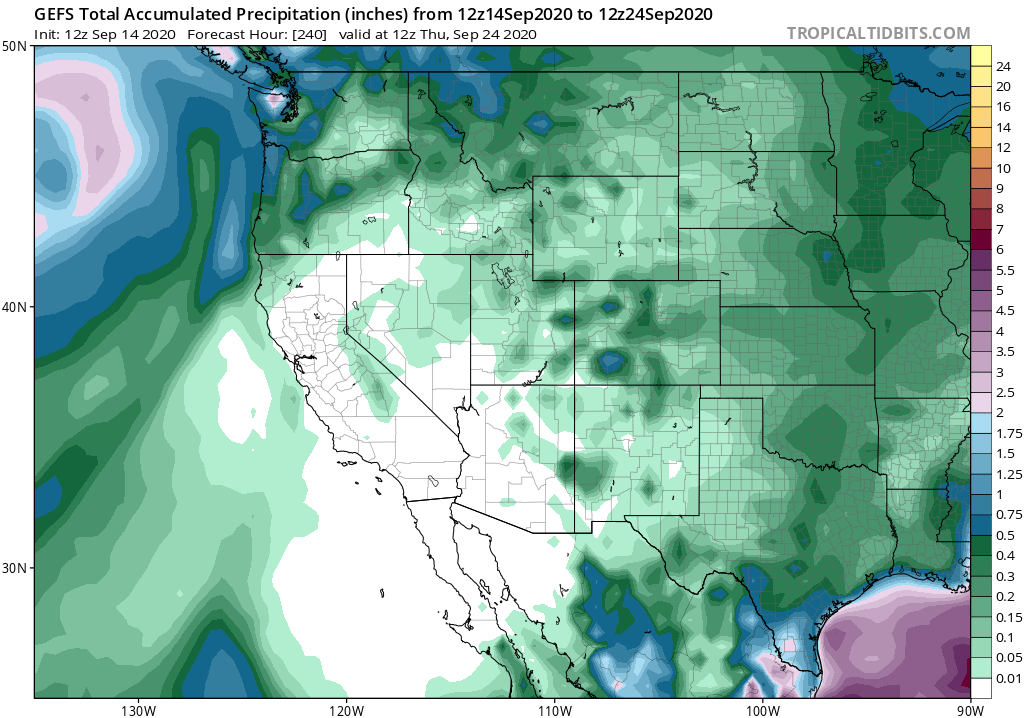

The other good news is that the incoming low pressure system will bring a round of modest but widespread showers to the Pacific Northwest, from about the central Oregon coast northward into British Columbia. These PacNW showers will help to temporarily reduce fire intensity in these regions and clear the air. Despite much excitement over the weekend, however, it looks increasingly unlikely that substantial precipitation will fall anywhere in California from this event. Scattered light showers are possible across the far north coast and mountains–where there are indeed fires currently burning–but accumulations will likely remain around or under 0.1 inches. Some coastal drizzle from an enhanced marine layer is also possible as far south as the SF Bay Area, but that will likely only penetrate a few miles inland. Elsewhere in California, I don’t expect any precipitation to fall with this event.

One other possible fly in the ointment–it’s not likely, but there may be a slight chance that the incoming low could entrain enough subtropical moisture to lead to some elevated convective cloudiness later this week. This would be unlikely to generate any precipitation at the surface, but there is a *slight* chance that it could produce isolated dry lightning strikes over the southern Sierra. I am not overly concerned about this at the moment, since odds are low, but it’s something to keep an eye on given the magnitude of the ongoing fires in that part of the state.

The bad news: winds will increase across the northern part of California over the next couple of days, likely increasing fire activity and generating large fire runs in a northward and northeastward direction. In fact, a Red Flag Warning for these winds is currently in effect for most of northeastern CA, including the Bear Fire/North Complex region. These won’t be extreme winds, but they will probably still be enough to exacerbate fire conditions (despite some increased humidity that will accompany them).

Temperatures will continue to run below predicted levels until the smoke substantially clears, which should happen in the next day or two. Thereafter, I do expect a small warming trend to near or slightly above seasonal levels by the coming weekend–although no big heat waves are on the horizon. There are hints of a possible brief offshore wind event this coming weekend as well, so that will also have to be monitored from a fire weather perspective.

Once again, I am sorry that I don’t have any solidly good news to convey in this blog update–though I think many may be cheered by the prospect of improving air quality, at least.

And finally: I hope everyone is hanging in there in these seriously trying times. On that note, I will simply leave you with my own sentiment regarding the ongoing wildfire crisis (among other things):

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.