Much-needed Sierra Nevada snowfall on the way! But a Miracle March? Not so fast.

Long absent, cold temperatures finally return to California

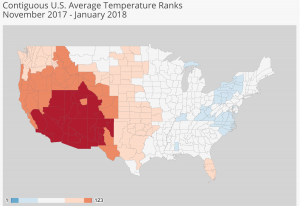

The 2017-2018 “rainy season” has been a pretty unusual one over much of California. The season to date has been nearly the driest on record to date over much of Southern California, and conditions have also become increasingly dry across the north as the season has progressed. Until mid-February, California had suffered through one of its warmest starts to the winter on record (in Southern California, and across most of the interior American Southwest, it was the warmest first half of winter on record). August-like temperatures baked coastal areas in February, and many folks in the southern half of the state began to wonder if cooler temperatures would ever arrive this year.

Fortunately, they finally did. Over the past 7-10 days, a fairly abrupt transition toward drastically cooler weather has occurred over the entire western United States–bringing unusually late-season sea level snowfall to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, and even some daily record low temperatures (including across much of California for a few days). This cold wave has been all the more striking since it immediately followed one of the warmest mid-winter spells on record in many areas. Along with the cold, somewhat more unsettled conditions developed over California as a trough set up along the West Coast. Weak, moisture-starved but very cold systems dropped southward along the coast, bringing a few coastal showers (in some cases with remarkably low snow levels) and more widespread Sierra Nevada snow. While these mountain snow showers were able to drop up to a foot of fresh powder in some spots, the relatively “dry” snowfall associated with this pattern change has barely registered on snow water equivalent charts. In fact, as of the last update on Friday, Sierra Nevada snowfall remains essentially tied with 2014-2015 and 1976-1977 for the least snow on record at this point in the season.

The stratospheric polar vortex splits, leading to wild Northern Hemisphere weather

Why did California suddenly flip from persistent record warmth and dryness to near-record cold (and well, slightly less persistent dryness)? The atmospheric flow pattern over the entire Northern Hemisphere is extremely amplified at the moment, with a pair of very strong blocking high pressure systems centered over the far North Pacific (south of the Aleutian Islands) and the far North Atlantic (near Greenland). These two features are acting like boulders in a stream, deflecting the normally west-to-east storm track (jet stream) over the mid-latitudes into a very wavy, north-to-south configuration. Alternating, essentially stationary zones of extreme winter warmth and cold have resulted from this wavy pattern all across the Northern Hemisphere.

One cold lobe has become stuck over western Canada, and this is the source region for all of the cold air in California (and across the entire West) in recent days. Simultaneously, the eastern United States just experienced its warmest mid-winter heatwave on record–shattering winter temperature records that in some places date back nearly two centuries (for reference: it was nearly 80 degrees in Boston and New York while San Francisco and Los Angeles failed to reach 60…in mid-February). Meanwhile, temperatures across much of Europe have plunged–and the coldest winter conditions in quite a few years are expected across a wide region in the coming days.

Most extraordinary of all, though, is the almost unbelievable warmth that has pervaded the highest latitudes of the Earth in recent days. As of this writing (today), the Arctic (including the North Pole itself) is experiencing temperatures warmer than have previously been recorded at any point during the winter season. Despite the still 24-hour darkness near the pole, the amplified jet steam pattern noted above has allowed plumes of subtropical moisture to penetrate very far poleward over the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans–yielding temperatures on the order of 55-65 degrees F above average and actually bringing *above freezing* conditions to northern Greenland and over the adjacent sea ice pack. Incredibly, sea ice in the Bering Sea near Alaska has been actively retreating in recent days.

The extreme event continues to unfold in the high #Arctic today in response to a surge of moisture and "warmth"

2018 is well exceeding previous years (thin lines) for the month of February. 2018 is the red line. Average temperature is in white (https://t.co/kO5ufUWrKq) pic.twitter.com/cLeMxSxvWo

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) February 25, 2018

Interestingly, there is a pretty clear culprit for all of this atmospheric mayhem–the recent “sudden stratospheric warming” (SSW) event and subsequent split of the stratospheric polar vortex. While a comprehensive explanation is beyond the scope of this already ballooning blog post, a two sentence version follows. The circumpolar (or polar) vortex, a band of upper-atmosphere winds which encircle the Arctic and typically act as a “fence” keeping cold, polar air in the high latitudes, can become disrupted by certain processes (like a SSW event). Upon disruption, cold air can suddenly escape the Arctic “fence” and spill southward; extreme temperature contrasts between alternating zones of liberated Arctic cold and relatively warm oceans can reorient the jet stream into a wavy north-south pattern, bringing periods of extreme weather throughout the hemisphere.

The good news: significant rain and heavy mountain snow (finally) on the way!

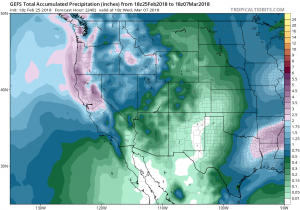

There is finally some good news to report: widespread rain and heavy mountain snowfall are imminent across nearly all of California! Another cold and relatively moisture-starved system will slide down the coast again tonight and Monday, though this one will have a slightly more favorable over-water trajectory. As a result, significant mountain snowfall is likely, and some accumulations down to as low as 1500-2000 feet are once again likely. The biggest difference between this system and recent ones is the increased potential for coastal showers (and even some thunderstorms with small hail). Precipitation (and a few thunderstorms) are most likely across Northern California, but a chance of some legitimate showers will also extend into SoCal by Tuesday (where some isolated t-storms are also possible). This does not appear to be a big rain-maker, but it will set the stage for what appears to be a stronger system later in the week.

The second system, as currently depicted by the models, looks like a respectable and cold late-winter system. The Sierra Nevada will be the biggest beneficiary–and may see 1-2+ feet of new snowfall from this storm (which means that the highest peaks could see as much as 3+ feet of pretty dry powder, derived from 1-3 inches of liquid equivalent, by the time all is said and done). There is still some inter-model disagreement between the GFS and ECMWF regarding how much rain makes it to SoCal with this second storm. Earlier solutions suggested the potential for a major rain event, but that now appears rather unlikely. Instead, I would expect to see some light-to-moderate accumulations over most of SoCal, but with some significant boom/bust potential. Why? This is not anticipated to be a particularly strong or moist system from a dynamical perspective; its greatest asset will be the very cold air aloft associated with it. Storms such as these sometimes “fizzle” south of Point Conception, and it’s possible that happens this week. Still, this will likely be the most significant precipitation event across most of the state over the past 6-7 weeks. (A note for the folks downstream of the Thomas Fire burn scar in Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties: the National Weather Service is keeping a close watch regarding the risk of burn scar debris flow/flood risk in the coming days, but right now it looks pretty low. The only exception would be if an isolated thunderstorm downpour occurs at some point this week, but that potential looks pretty minimal at moment).

But will this be a Miracle March? Right now, that’s not our trajectory.

Recent model forecasts substantially disagree regarding what comes next. Both the GFS and ECMWF suggest the trough axis will continue to retrograde (shift westward) further away from California in the 7-10 day period, bringing at least a short period of dry conditions. There are hints that a stronger subtropical ridge may try to build in at that point, which unfortunately would tend to keep things relatively dry once again (especially in Southern California). But given the highly disrupted state of the Northern Hemisphere atmosphere at the moment, I wouldn’t put too much stock into long-range ensemble forecasts at the moment (contrast this with the last blog post, when the opposite was true).

The precipitation this week is undoubtedly good news, especially in the Sierra Nevada. The upcoming snowfall will likely result in some great skiing conditions, and the low elevation snow accumulation may help act as a bit of a buffer against early spring warming. But amazingly, even 2-3 feet of dry powdery snow (along with 1-3 inches of liquid equivalent) means we will essentially keep pace with the 1976-1977 snow year going into early March (we will, at least, probably pull slightly ahead of 2014-2015). But unless there is a second, more sustained wave of storm activity later in the month (which, as always, remains possible), we are not yet on track for a “Miracle March” redux. For those keeping track, March 1991 brought nearly 300-400% of average precipitation in the Sierra Nevada–greatly alleviating what might have been an even worse drought year. Over the next 2 weeks, the ECMWF ensemble suggests that NorCal will see around 110-140% of average precipitation for that interval, and SoCal 60-100% of average. In other words: over the next 10 days or so, we’ll essentially be keeping pace with average precip (and perhaps recouping a small amount of our enormous deficit up north). In the mean time, I’ll be keeping my fingers crossed for a second major storm cycle later in the month…

Much-needed Sierra Nevada snowfall on the way! But a Miracle March? Not so fast. Read More »