Hot, dry summer continues in California; severe fire season looms; El Niño update

Overview of recent conditions

In many ways, the weather over the past few weeks has been pretty typical of early summer in California.

It’s been hot in the inland valleys, and not so hot near the coast, with a sharp gradient in between. Conditions have been largely dry, though an increasingly moist monsoonal flow has finally brought respectable thunderstorms to some mountain and high desert regions lately. We’ve seen a modest marine layer along the coast, and periodic heat waves inland that have brought sweltering temperatures to Central Valley and southeastern desert communities. None of these events is particularly noteworthy for late June and early July.

Drought update

Despite this semblance of pseudo-normality, though, there are a number of rather stark reminders that conditions are far from what would normally be expected this time of year.

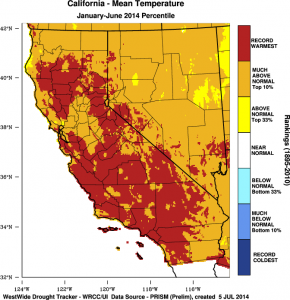

California continues to endure its warmest year on record to date (as of May 31st; I’ll update this point in a day or so when the official June numbers become available). Huge wildfires are burning with an intensity not normally witnessed until the driest days of September and October, and various metrics suggest that wildfire risk in many regions is at or near record high levels. The Sierra snowpack is long gone–and snowmelt-driven river and streamflows into the state’s reservoirs continue to plummet. An even greater fraction of California is experiencing “exceptional” (i.e. maximum-severity) drought conditions than just a few weeks ago–a region which now includes both the San Francisco Bay Area and the greater Los Angeles Metro area. Given California’s distinct wet winter/dry summer climatology, it’s extremely unlikely that this overall picture will change much between now and the start of the next rainy season.

________________________________________________

Medium-term outlook

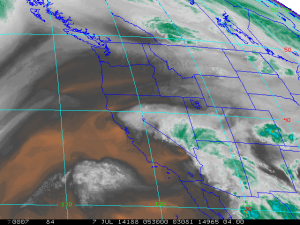

Monsoonal moisture continues to stream northwestward over much of California this evening, and will continue to do so periodically over the next week or more. High mountain and some high desert regions have already experienced some locally intense thunderstorm activity in association with this moisture, but precipitation coverage overall has been quite sparse. There is a slight possibility that some of this moisture could spark some mostly dry, high-based convection over the next 72 hours over parts of northern and central California, which would of great concern fire weather-wise. However, at the moment it doesn’t look like we’re headed for a major “lightning bust” in the immediate future.

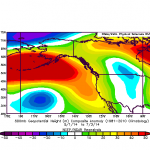

Hot to very hot conditions will continue over interior California, with widespread 100+ temperatures expected for much of the coming week. While this heat won’t extend all the way to the coast (where a shallow marine layer will keep things seasonably cool), the state overall will remain considerably warmer than average. Some moderation will probably occur late this week as a weak trough develops off the coast of California, but conditions will remain quite warm inland.

There has been some suggestion in recent numerical model forecasts that a more substantial push of southeasterly winds/monsoonal moisture may affect California during the first half of July. A slow-moving upper-level low may develop off the coast towards the end of the coming week, which may turn flow to the south or southeast over California by next weekend. If this relatively moist southeasterly flow from the Gulf of California and Desert Southwest can interact with some weak instability generated by the offshore low, there may be the possibility of a more widespread elevated convective event at some point in the 6-10 day period. Recent solutions have become a little less consistent regarding this possible evolution, but this probably bears close watching over the next week or so. I’ll have an update if this starts to appear more likely.

El Niño update

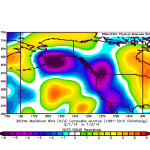

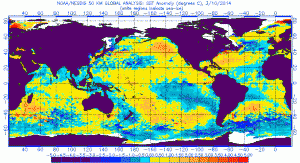

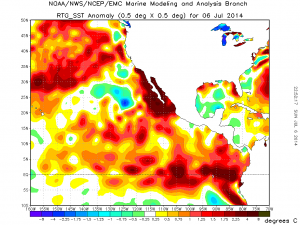

After a remarkably rapid warming of Eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures during early June as the powerful Kelvin wave from earlier this year surfaced, SST anomalies have recently begun to decrease. This has occurred because the large subsurface temperature anomalies have largely exhausted themselves and have not recently been reinforced by new warm water from the West Pacific. This evolution is consistent with recent coupled atmosphere-ocean model projections, but is somewhat different than what had been projected a couple of months ago, when more consistent warming was expected.

There’s a lot of speculation presently surrounding the “demise of El Niño” on the basis of this recent development, which I’d argue is just as premature as the equally confident headlines which–just a few short months ago–called for a “mega/monster/hyper El Niño” later this year. The reality is: the ocean-atmosphere system is very complex and responds to both foreseeable longer-term forces and unforeseeable random ones. What does this mean in the present context? Well, so-called “westerly wind bursts”–which help to enhance developing El Niño events by disrupting the prevailing equatorial trade winds and allowing warm West Pacific water to “slosh” eastward–typically result from individual low pressure systems (sometimes typhoons) that spin up in the West Pacific.

These sorts of events–which fall under the purview of “weather,” since they evolve on timescales of a few days to perhaps a week–are very difficult to predict more than a week in advance, yet they are fundamentally important to ENSO’s evolution. While we did finally witness a new (but fairly weak) westerly wind burst over the past week, the continued evolution toward an El Niño state will require additional and sustained westerly wind bursts later this summer, and we don’t yet know if that’s going to occur. The dynamical models appear to think so–since the ensemble mean remains fairly bullish in predicting a moderate-to-strong event by next winter (and, interestingly, above-normal precipitation in coastal California during the same time frame).

However, as recent events have demonstrated quite clearly, the real world sometimes deviates from even our most reasoned expectations. There are a few things we can say with high confidence about conditions over the next few months, though. Sea surface temperature will likely remain quite elevated in the Eastern Pacific (including along the coast of Southern California, where water temperatures are currently as high as the upper 70s in San Diego Bay, and a very impressive 3-6 F above normal across a wide region).

This will probably keep near-coastal regions in the southern part of the state warmer than usual for the remainder of summer, and may allow for a higher-than-usual likelihood of tropical cyclone remnant moisture to affect California for the rest of summer and early fall.

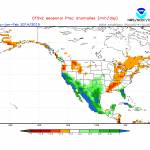

Finally, recent trends and current model projections suggest that SST anomalies by the fall and winter months may be quite different across the North Pacific than in recent years–more reminiscent of the positive phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation than of the negative phase, which has been the prevalent condition since the last big El Niño ended in 1998. Historically, such SST configurations have favored wetter winters in California, though it’s not at all clear that this will be the case in 2014-2015. For now, it’s probably wisest to prepare for what will nearly certainly be a hot, very dry 3 months to come.

As a quick reminder: for frequent weather/climate micro-updates through the summer, follow Weather West on Twitter and Facebook!

© 2014 WEATHER WEST

Hot, dry summer continues in California; severe fire season looms; El Niño update Read More »