Warm subtropical system to bring heavy New Year’s rain to SoCal before a somewhat quieter pattern takes hold by mid January

Taking stock of recent storm impacts–and the exceptional SoCal wet period isn’t over yet

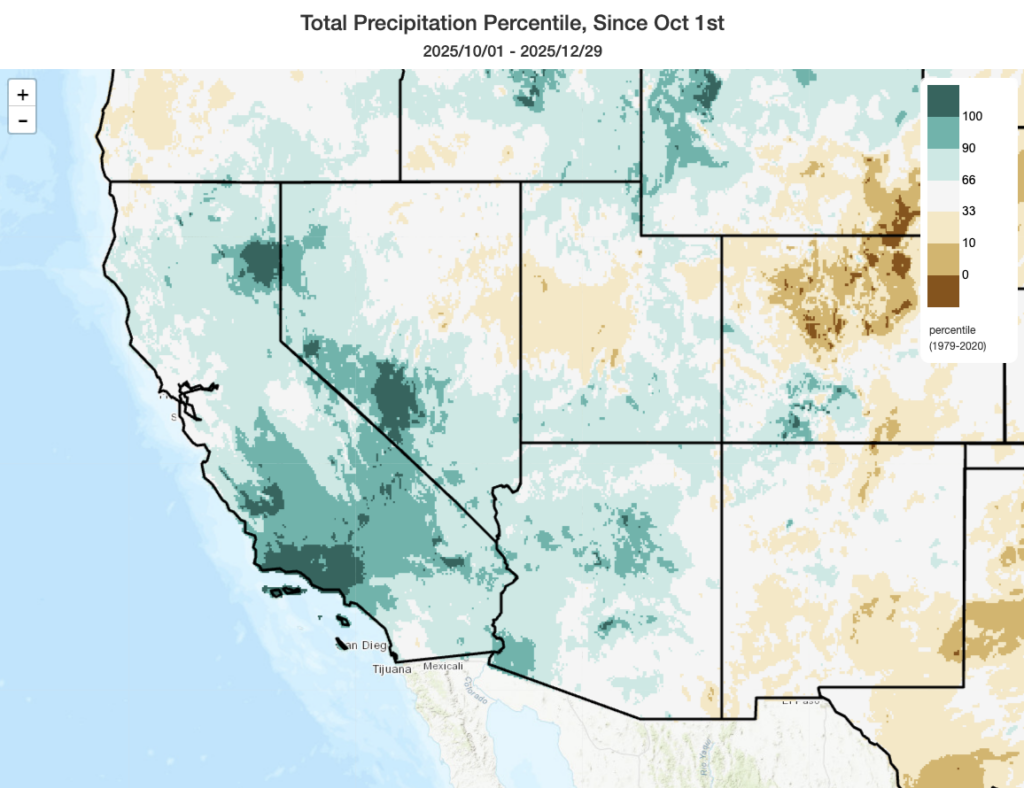

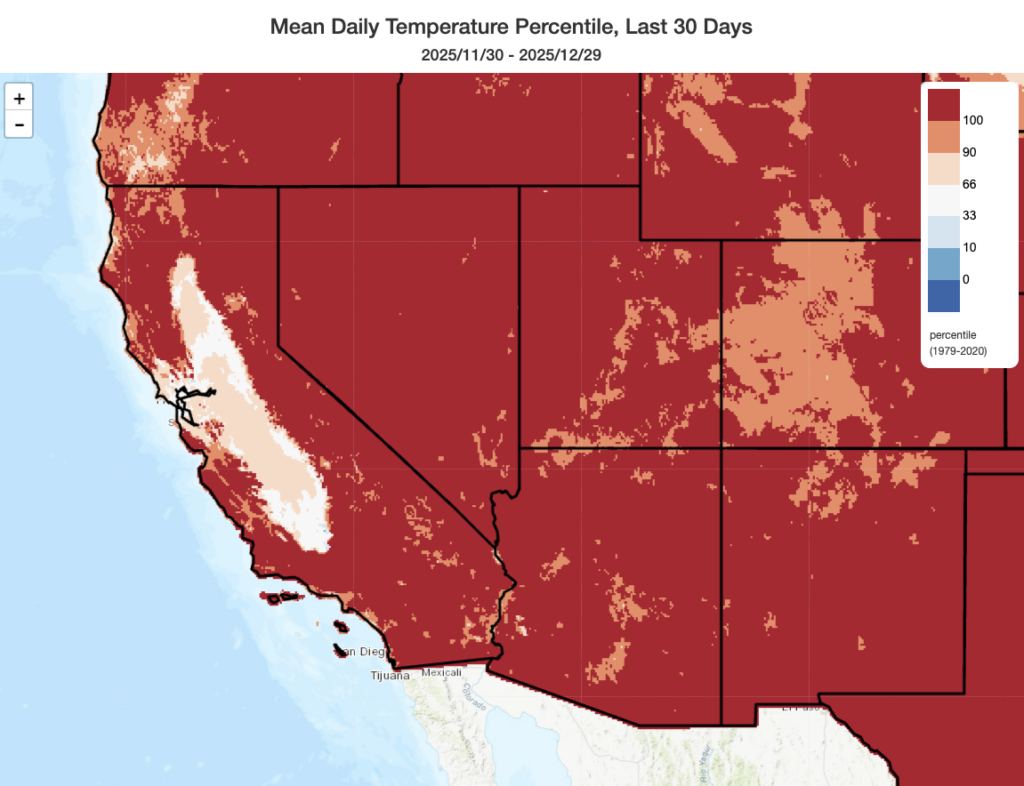

Since October, a historically exceptional period of weather has unfolded across California. Unusually early and intense autumn rains soaked southern and central California–de-fusing fire season before offshore winds ever arrived in force. Then, for much of November and early December, an eerily quiescent period brought a period of remarkable temperature contrasts–between the persistently balmy and often record-warm conditions across southern California and in nearly all of California’s upper elevation regions (including the Sierra Nevada and Coast Ranges) and the unceasingly cold, damp, and dark conditions under a weeks-long tule fog layer in the Central Valley and parts of the SF Bay Area. Meanwhile, in the Pacific Northwest, exceptional warm storms brought widespread and severe flooding; simultaneously, record warmth and lack of precipitation brought a record-low snowpack to most of the interior West. When the official statistics are in and the final numbers crunched, it’s quite likely December 2025 will have been the warmest on record for most of the U.S. West by a considerable margin–and possibly even for California, despite the relative coolness in the Central Valley.

Then, over the past 2 weeks, a series of major storms brought another round of exceptional precipitation and even severe thunderstorms to Southern California–causing widespread, locally destructive, and unfortunately deadly–flooding. (The SoCal death toll from recent flooding might have been considerably higher were it not for the pre-positioned swiftwater rescue teams and helicopter crews–who together plucked well over 100 people from fast-moving floodwaters.)

All of this, it is hard to believe, happened in the same calendar year as the devastating Los Angeles wildfires in January 2025–which occurred during an extreme Santa Ana wind event amid a record-dry start to winter following two consecutive years of near-record wet conditions in the southern part of the state. The resulting wet-to-dry and then dry-to-wet whiplash has been, well, intense. I’ll have more to say about it later, including during my upcoming YouTube livestream, but for now I’ll just say this: At least we don’t have to worry about exceptional wildfire risk this winter in Southern California.

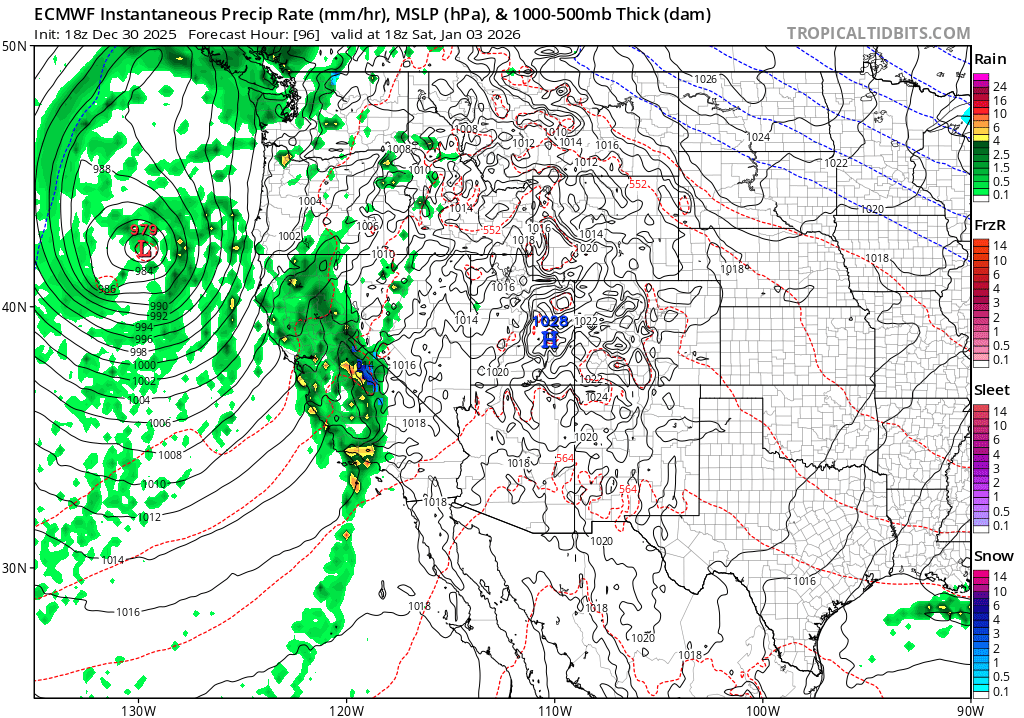

Warm storm from unusually low deep subtropical latitudes will bring abundant warm rain to SoCal on New Year’s

The exceptionally wet pattern in SoCal isn’t over yet–we’re going to squeeze in one more major rain event before the calendar year is over (though the heaviest downpours may occur on New Year’s Day). The next system has already developed, and it has done so at an unusually low latitude: west, even southwest, of Baja California! This system’s far southerly origins endow it with an unusually warm and moist airmass (yes, again); this will feel positively balmy as it moves into SoCal overnight into tomorrow. Some lighter initial rainfall is possible tomorrow, but heavier rain and gusty winds may develop overnight tomorrow (on New Year’s Eve) before the strongest part of the storm moves in on Thursday morning.

Right now, this system does not look especially dynamically impressive. But it does have, once again, a very impressively warm and moist tap; the deep subtropical origins of the parent air mass make it somewhat convectively unstable, as well. In fact, there have been large areas of vigorous and nearly continuous thunderstorm activity associated with the southern quadrant of this storm over the past 48 hours. While these thunderstorms are expected to die down somewhat between now and the storm’s time of landfall, some may persist all the way to the Los Angeles area on Thursday morning as plentiful moisture, weak synoptic forcing, and adequate surface-based instability will be present for at least isolated coastal thunderstorm activity. Some of the high-res models actually show a very impressive line of heavy storms right over LA during the Rose Parade on Thursday morning, so that could get interesting. And while the risk of severe thunderstorms does appear lower with this storm than the last, some fairly impressive low-level hodographs (indicative of strong wind shear in the very lowest level of the atmosphere) might still manage to support another isolated waterspout or brief tornado in or near LA County.

The main risk from this storm, however, will be renewed risk of rockslides, mudslides, and debris flows in steeper terrain across SoCal–with an isolated risk of flash/urban flooding as well. Flooding risk will be highest in the mountains and deserts that saw very heavy rainfall last week, though urban and roadway flooding could once again occur during the (briefer) window of torrential thunderstorm downpours that are possible on Thu AM. This is the kind of system to keep a close eye on for sneaky flash flood risk, as although overall precipitation accumulations will be much lower than last week, isolated thunderstorms in a very moist subtropical airmass could drop multiple inches of rain on a very localized basis rather quickly, and almost anywhere. So…certainly a day to keep and eye or two to the sky!

Because this system will be so warm, no snow at all is expected in the SoCal mountains and only minimal snow is expected at the very highest elevations of the Sierra (above 8-10k ft); some rain may fall on existing snowpack below 8-9k feet, though significant flooding is not expected as NorCal precipitation will be considerably lighter.

Relatively active CA weather pattern to continue for ~7-10 days before drier, calmer conditions possibly return

Following the Wed-Thu system, a secondary colder storm will likely arrive by Saturday, and will be focused more on NorCal vs SoCal. The initial airmass will, once again, start out very warm with very high snow levels; however, as with the last storm sequence, much colder air is likely to filter in behind the initial front and bring a period of much more typical January snow levels that will add some fresh power atop the thawing/melted slush from days previous.

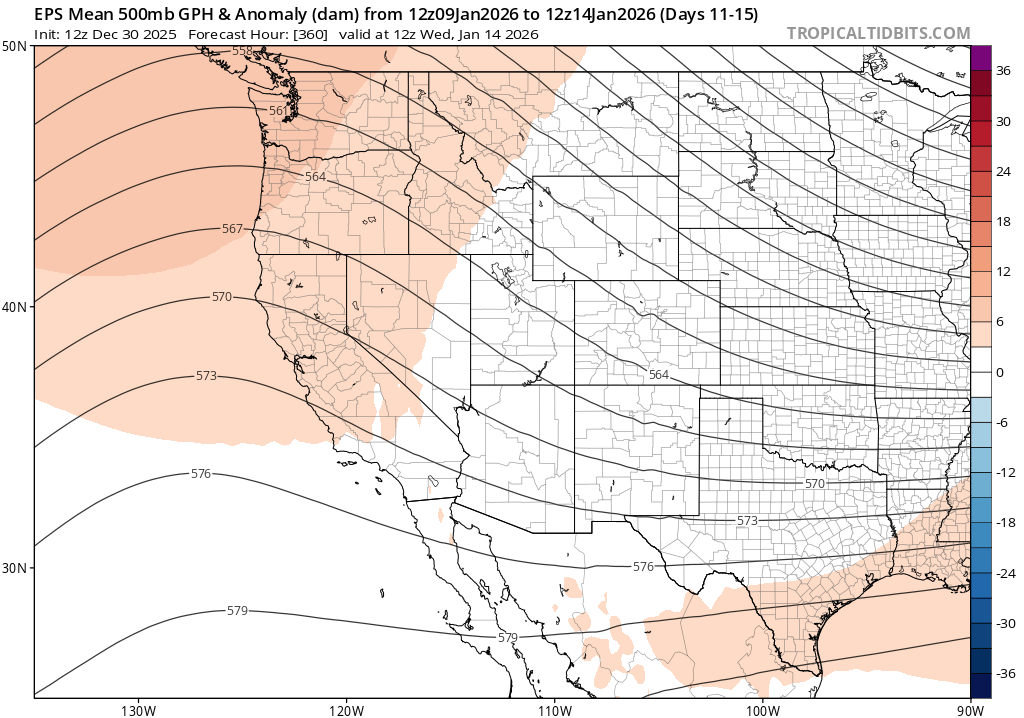

Looking ahead into January, a relatively active weather pattern may continue for another 7-10 days in California; thereafter, there are hints of a potentially more sustained break in mid-January with a West Coast ridge potentially developing. This is a relatively low-confidence pattern, though, so don’t hold me to it! I’ll be following this more closely in the new year.

Thanks for being part of the Weather West community as it approaches 20th anniversary!

Believe it or not, the Weather West blog has now been around for a nearly a full 20 years–a milestone that will be reached in 2026! Websites in general tend not to have a very long lifespan on the internet, especially these days, and weatherwest.com’s “continuously active” status since 2006 apparently puts it above the 99th percentile of longevity among all websites that have ever existed. That is a remarkable testament to the size, breadth, and dedication of the community that has grown here over the years. It’s now typical for blog posts here to attract thousands of (almost always!) thoughtful and on-topic comments; Weather West readership has grown from a mere hundreds per year in the beginning to a couple of million folks annually in recent years. And I’ve expanded my presence across a widening range of social media platforms (including YouTube, Bluesky, Twitter/X, Threads, and Mastodon) in hopes of reaching even wider audiences.

Folks have recently been asking how they can support Weather West, so I’ll offer a few specifics. My main goal is to make weather and climate information accessible to all; I’ve never put content behind a paywall, and have no plans to in the future. Your readership, and continued engagement with the broader Weather West community, is the most important form of support!

That said, if you do want to go above and beyond, you’ve got a few options. First, you can join the @WeatherWest YouTube channel as a member (though everyone can still subscribe for free!). You can also support Weather West directly via Patreon or Buy Me A Coffee. You might also consider making a contribution to University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, my current employer and active facilitator of my public-facing weather and climate role!

A special New Year’s Eve livestream at noon Pacific Time

In this special New Year’s Eve livestream (don’t worry, I’ve scheduled it at noon for those with evening plans!), I’ll offer a recap of the remarkable 2025 weather year in California–including the “double whiplash” cycle in Southern California (from very wet in 2023-2024 to record dry in early 2025 to (near) record wet again by the end of the year). I’ll also discuss the incoming New Year’s storm, and finally offer a brief update on the evolving situation evolving with the proposed dismantling of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). See you then!