Ridiculously Resilient Ridge continues to shatter records, but pattern shift may be approaching

Current weather summary

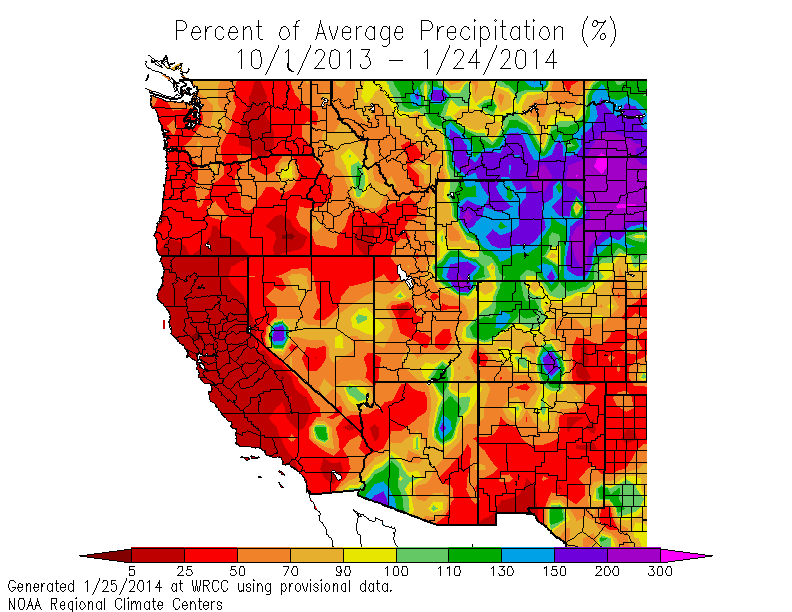

Exceptionally warm, dry, and stable weather conditions have prevailed over California since early December. Precipitation totals over the past 40-60 days have been near zero across most of the state of California, with only very light precipitation observed in the north. Various observing sites have now surpassed their previous all-time records for the greatest number of consecutive dry days during the “rainy” season, and these new records will almost certainly be extended at least a few more days as bone dry conditions continue. Nearly all of California has been experiencing record high temperatures on a daily basis over the past several weeks, including the establishment of new all-time January record high temperatures in a few places (most notably Sacramento, at 79 degrees).

In addition to this impressive stretch of record-breaking January warmth, the observed atmospheric flow pattern over California has been downright bizarre over the past couple of weeks. Weak disturbances have been propagating westward or northwestward over the state around the south side of the highly persistent ridge, bringing periodic mid and high-level cloudiness and occasional offshore winds. This flow pattern is completely reversed from its normal orientation (weather systems in winter typically move eastward over California). Just to give some indication of how strange this pattern really is: the moisture source for the observed cloudiness across parts of California over the past few days is the subtropical East Pacific Ocean southwest of Baja California (rather than the Gulf of Alaska).

The increasing impacts of California’s extraordinary dry spell

California Governor Jerry Brown formally declared a Drought Emergency on January 17, and a slew of voluntary or mandatory water restrictions have been rapidly enacted across Northern California since the start of the calendar year. Certain communities dependent on local water sources are facing extreme shortages as supplies are already running dry. While most major urban areas in California have a larger “storage buffer” in the form of shared water supplies in the larger reservoirs around the state, even these water levels are plummeting as runoff approaches zero in most places.

The secondary effects of the drought have also becoming more apparent in January. Extreme fire weather conditions and associated Red Flag Warnings have been issued multiple times for large parts of the state that have not experienced these conditions during mid-winter in living memory. Localized dust storms are starting to occur in the San Joaquin Valley, where powder-dry topsoil from hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland that has gone un-planted and un-irrigated as a result of the drought is being lofted by unusually strong southeasterly winds. Air quality as a result of this stagnant weather pattern has been extremely poor throughout the state, but conditions in the Central Valley have been especially bad, where levels of fine particulate matter (PM-2.5) have reached dangerous levels even for healthy adults. The Sierra snowpack is nearly nonexistent–only 5-7% of normal in the north–and the winter sports industry has come to a virtual standstill except at those venues capable of generating “artificial snow.” In short: it does not feel very much like winter here in California.

Signs of weakness in the “RRR”, or just more false hope?

On quite a few occasions over the past four months, our best atmospheric models have suggested that a pattern change might be in the works: that the “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge” might finally be breaking down or at least moving into a position that would allow some storms to reach California. So far, however, the models have been wrong in every instance: the RRR has remained stronger and more persistent than projected by the models. At the time of this writing, however, there are more convincing signs that there may be at least a temporary weakening and/or shift in the persistent ridging over the East Pacific that would finally allow for some precipitation to reach California for the first time in nearly two months.

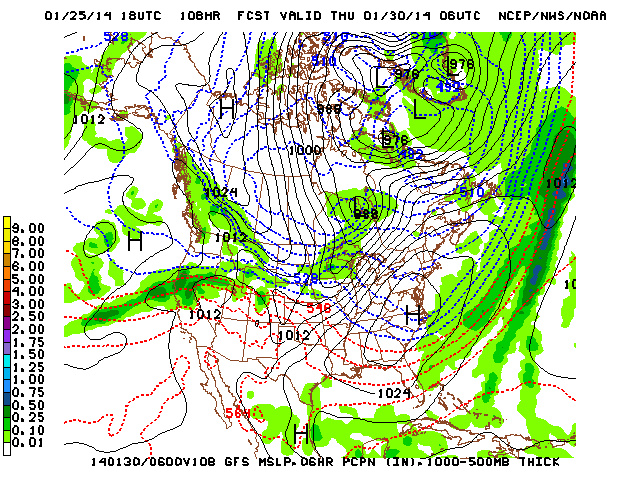

California will likely experience 3-5 more days of dry weather and record-breaking high temperatures before a Pacific storm system takes advantage of a weakness in the mean ridge and approaches the state from the northwest. It’s not clear at this point how much precipitation this system will bring to California–since while it appears to contain a fairly large amount of atmospheric moisture, the system will have to overcome an exceptionally dry existing airmass. That said, it does appear that there’s a chance that NorCal could see a soaking/moderate rain event later this week. While this event probably won’t have a major impact on the extreme drought conditions in California, it may be enough to settle the dust, clear the air, and reduce wildfire risk temporarily.

Few prospects for significant drought relief in the medium to long term

In the longer term, the evolution of the large-scale pattern is even less clear. The models have already backed off their more aggressive solutions from a couple of days ago (i.e. strong zonal flow and significant storminess in California) and are now (once again) depicting a familiar pattern of high-amplitude blocking over the far eastern Pacific. There is one big difference between the projected pattern and what we’ve observed recently, though: the blocking ridge may set up somewhat further to the west as we enter February, which would put California in the region of anomalous northerly flow on the downstream side. In practical terms, this means that we can almost certainly bid our record warmth goodbye and might possibly need to prepare for very cold conditions. Some recent runs of the GFS and ECMWF have depicted exceptionally cold (yet mostly dry) conditions developing over the West during the first half of February, which would constitute a drastic change in the weather but not help much with the extreme drought conditions. It is worth noting that persistent, high amplitude blocking in this region has historically been associated with most of California’s major Arctic outbreaks, including the notable February 1976 and December 1990 events. However, it’s still far too early to discuss the details of this possible pattern evolution, and it’s entirely possible that our not-so-good friend the RRR could set up shop once again in a position favorable for unusually warm conditions in California. Regardless: what is becoming increasingly clear is that drought-busting rains are not headed our way for the next two weeks, at least.

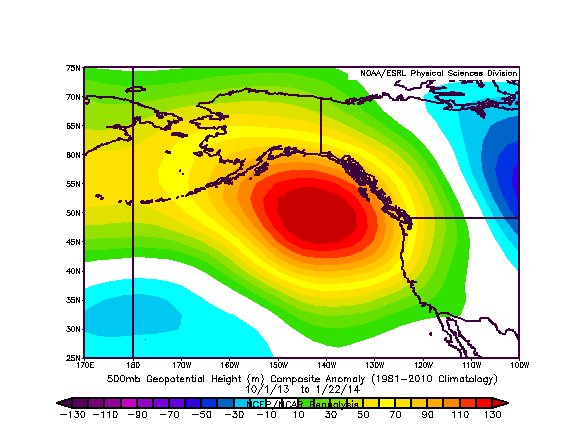

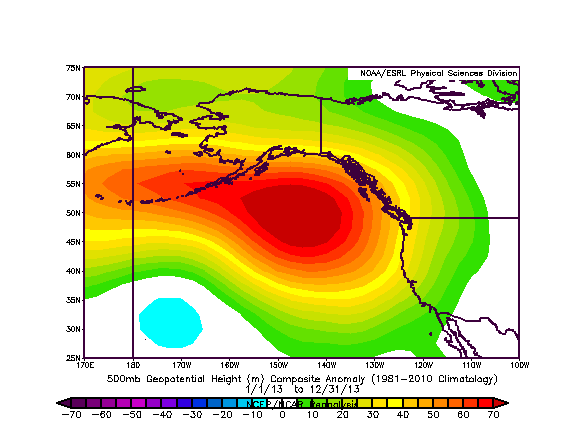

The RRR during calendar year 2013 (left) and Water Year 2013-2014 (right)

In the even longer term, current seasonal projections suggest that California will continue to experience below-normal precipitation for the rest of the rainy season. While it would only take an atmospheric river or two to really jump-start river runoff and reservoir inflows, the prevailing pattern of weak zonal flow and amplified East Pacific ridging does not favor this kind of critically-needed precipitation event. I’ve previously discussed the possible role of a region of very high sea surface temperature anomalies in the North Pacific in reinforcing the RRR, and unfortunately the seasonal climate models suggest that the warm pool will persist right into the summer. In the really, really long term, the dynamical ocean models are currently projecting an increasing chance of El Nino conditions developing across the tropical East Pacific over the summer, though even if this projection comes to fruition it will unfortunately occur too late to affect rainfall potential for this water year.

A note on the severity of the current California drought

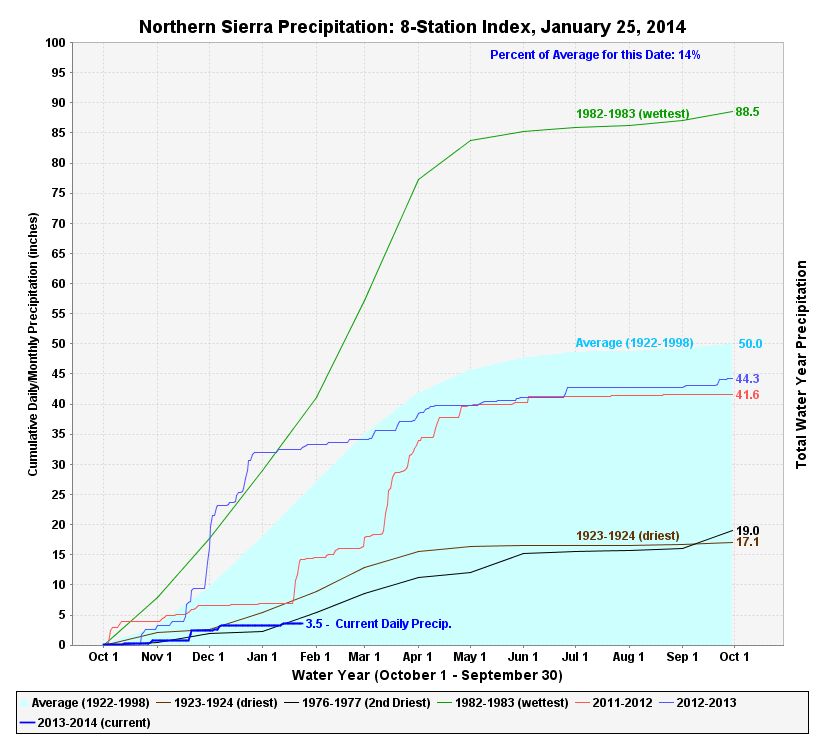

Calendar year 2013 was the driest on record in California’s 119 year formal record, and likely the driest since at least the Gold Rush era (the current event is without precedent in San Francisco’s precipitation records, for example, which go back to 1859). Observed precipitation for the current (2013-2014) water year–which began in October 2013–is tracking below all previous water years, including both years in the 1976-1977 drought and the extremely dry winter of 1923-1924. While we don’t know for sure what the rest of winter holds in store–and it is certainly still possible that February and March bring much-needed rainfall–current precipitation deficits are so large that it would require very heavy, sustained precipitation for the rest of winter to bring us up toward average values. In fact, an informal analysis suggests that we would have to receive more precipitation between now and the end of the rainy season than has ever been observed in California during the February-April period in order to erase the deficit. Therefore, even a repeat of the (highly alliterative) drought-busting late-season events in California’s meteorological history–the infamous “Fabulous February”, “Miracle March“, and “Awesome April” wet spells of years past–would probably not be enough to end the drought.

For now, I’ll be keeping an eye on the medium range forecast models for any signs of significant drought relief. In the meantime, I strongly encourage everyone in California to be mindful of their water usage in the midst of these increasingly severe drought conditions and to take active conservation steps in advance of what promises to be a challenging summer and fall ahead. Stay tuned.

© 2014 WEATHER WEST