A wildfire catastrophe of almost unimaginable scale in Northern California

It’s a refrain that Californians have heard all too often in recent years: yet another extremely destructive, fast-moving wildfire has torn through multiple communities, leaving widespread destruction in its wake. But this time, the numbers and details are staggering even by comparison to recent disasters in the fire-weary Golden State. The Camp Fire, which ignited in a wooded area in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Butte County and quickly overran the town of Paradise last Thursday, has been responsible for over 70 deaths. Over one thousand people remain unaccounted for as of today–a number that has, ominously, been rising steadily now for over a week. Nearly 15,000 structures have been destroyed, including essentially the entire town of Paradise (population: 27,000).

The Camp Fire is already, by a very wide margin, the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history. In fact, in terms of lives lost and buildings burned, the Camp Fire may be the worst North American wildfire in the modern firefighting era. To put the human toll in perspective: the confirmed number of deaths during this catastrophic fire exceeds that during any California earthquake since at least the 1933 Long Beach quake (exceeding both the Loma Prieta (1989) and Northridge (1994) events). Details emerging from the grim and ongoing recovery effort suggest that the final toll could ultimately be higher than any California natural disaster since the 1906 earthquake and firestorm in San Francisco. Even for those of us who follow these kinds of events closely–it has been genuinely shocking to watch this tragedy unfold.

Elsewhere in Northern California, an extremely dense layer of choking smoke from the Camp Fire has led to one of the worst air pollution episodes in modern history from San Francisco to Sacramento to Chico, and all points in between. Unusually stagnant air, due to persistent atmospheric pressure and sinking air/weak offshore flow, has allowed smoke to accumulate in the Central Valley and seep westward over the Bay Area, lingering even over the adjacent Pacific Ocean. Air quality of the past week has consistently been worse in Northern California than anywhere else on Earth–including the infamously polluted megacities of Beijing and Delhi–due to extremely high levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5, which is very different indeed from the more common “photochemical smog.”) Most schools and universities have cancelled classes until further notice; the Big Game between Stanford and UC Berkeley has been postponed until December; and N95 respirators have become a common sight even in Silicon Valley and among tourists visiting the Golden Gate Bridge.

And certainly not to be forgotten: another extremely large and highly destructive wind-driven fire, the Woolsey Fire, destroyed hundreds of homes and forced the emergency evacuation of Malibu and other parts of western Los Angeles/Ventura County. The fire burned all the way to the Pacific Ocean–and at one point necessitated the reversal of all lanes on the Pacific Coast Highway to facilitate the urgent evacuation of several coastal towns. This fire also took several lives, destroyed important infrastructure, and burned a majority fraction of the much-visited Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. Under normal circumstances, this huge blaze would be a larger story in its own right–but the even more massive scale of the human tragedy still unfolding in Northern California has commanded considerably more attention over the past few days.

If you are interested in helping out in the aftermath of these disasters, please keep in mind this advice from disaster response experts: contribute either cash or your time (especially if you have relevant special skills)–not physical items. Local news outlets have been maintaining growing lists of ways to make a difference. The need will only grow in the weeks and months to come; 20% of the total housing stock in Butte County has disappeared overnight, and as many as 30,000 people may be without homes to return to after all is said and done.

Yet another hot summer/dry autumn sequence set the stage for explosive fire conditions

What, exactly, happened in the early hours of the Camp Fire that made this particular fire so unbelievably deadly and destructive? A confluence of unfortunate factors was at play. The ignition point of the fire was northeast of Paradise; strong offshore & downsloping winds (blowing from northeast to southwest) gusting over 50mph pushed the fire directly toward town with astonishing speed. Vegetation in the region has been at record-dry levels for the time of year due to a combination of anomalous summer warmth and a conspicuously dry start to the rainy season this autumn. The combination of extremely low fuel moisture and drying downslope winds resulted in an essentially unstoppable, miles-wide fire front moving from east to west down the slopes of the Sierra Nevada foothills all the way into the Northern Sacramento Valley east of Chico (ultimately, the fire jumped Highway 99 and only slowed as it approached irrigated agricultural fields to the west).

Paradise was a community at especially high risk of wildfire. The town is surrounded by a mix of dense and sparser forest and mixed brush; some of this land has been logged commercially, and other areas actually experienced a fairly intense fire less than a decade ago–locally thinning fuels even further. Yet these vegetation types, given the degree of dryness and winds, were still enough to fuel what ultimately became California’s worst wildfire on record. Paradise also had a relatively limited number of escape routes for its nearly 30,000 residents–and the fire came from a direction that cut some of these off early in the event. Thus, despite putting into place an organized evacuation plan (which had been rehearsed by the entire town in recent years), the frantic evacuation led to gridlocked traffic in the immediate path of the fire front. Thousands were trapped on the roads leading out of town when the fire moved through, and the number of harrowing stories (and videos) emerging from the fire zone is genuinely startling. Tragically, as many weather and fire experts had initially feared, it is starting to appear that many folks stuck on these roads and in neighborhoods cut off by the rapid advance of the flames were ultimately not able to escape in time.

Interior Northern California experienced one of its warmest summers on record (again) in 2018; in the vicinity of the Camp Fire, 4 of the 5 warmest summers on record have occurred in the past 5 years. (Residents of San Francisco would be forgiven for not realizing this, as in a localized zone along the NorCal coast summer 2018 was actually a relatively cool one by recent standards). Even more importantly: California’s rainy season has been greatly delayed again this year–something that has allowed both the Camp Fire in NorCal and the Woolsey Fire in SoCal to burn so aggressively so late in the calendar year. It is genuinely astonishing that California’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire on record has now occurred in Butte County in November–a place that has typically already received over 5-6 inches of rainfall by the date of the Camp Fire’s ignition. In this part of California, there is essentially no precedent for large wildfires at this time of year as the rainy season is typically well underway by this point. This is unsettlingly analogous to the record-setting Thomas Fire in SoCal less than a year ago, which became California’s then-largest wildfire in the middle of December (a dubious record that has already been eclipsed by the Ranch Fire in Mendocino County this past summer). In our recent work, we pointed out that much of California appears to be in the early stages of an autumn drying trend that will likely become more pronounced as the climate continues to warm.

If Northern California had received anywhere near the typical amount of autumn precipitation this year (around 4-5 in. of rain near #CampFire point of origin), explosive fire behavior & stunning tragedy in #Paradise would almost certainly not have occurred. (1/n) #CAfire #CAwx pic.twitter.com/2LBKjSVBMF

— Dr. Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) November 10, 2018

Climate change is a wildfire “risk multiplier” in California, but not the only relevant factor

There has been much discussion over the past week regarding the role of climate change in setting the stage for disasters like the Camp Fire. While the scientific conversations will continue to evolve in the coming months and years, one thing is abundantly clear: warming temperatures and changing precipitation seasonality are unquestionably increasing the already high wildfire hazard across the American West, including California. This effect comes mainly from the increasing aridity of vegetation–which causes existing fires to burn hotter, faster, and more intensely. Fire season is now considerably longer than it used to be–a reality that has become painfully clear over the past several years in California. But other human factors are at play as well. The encroachment of urban and suburban developments into high fire risk zones in the “wildland-urban interface,” along with the burgeoning population of relatively isolated communities in heavily vegetated areas, have greatly increased the overall risk. And in certain vegetation regimes, the legacy of a century-long practice of “total fire suppression” has led to a deficit of natural, low-intensity “good fire,” and a subsequent increase in the density of flammable vegetation. Indeed, as we pointed out in our recent perspective piece: wildfires are complex events, and no single factor is to blame for a particular fire. But on top of everything else, climate change is acting as wildfire “threat multiplier” in a place that hardly needs any additional contributions to wildfire risk. There are some short-term actions we can take to mitigate these hazards, and I imagine the scope of the current disaster will be a catalyst for some serious introspection at the state level in California. I’ll revisit some of these ideas in the months to come, but for now…I promise it’s time for some good news.

Finally some good news: significant rainfall by Thanksgiving, especially in NorCal

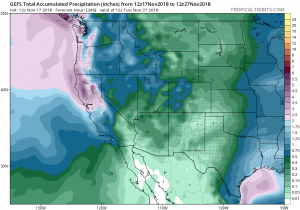

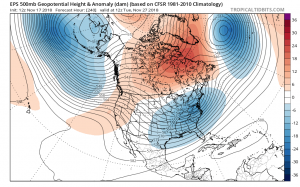

Just about everyone will be happy to hear that rain is finally headed for California–with significant accumulations likely by Thanksgiving, especially in NorCal. The first system or two early this week might end up being “sacrificial” in the sense that they will largely fall apart as they move into the very dry and stable antecedent airmass. But subsequent storms later in the week, especially from Wednesday through Saturday, could bring widespread (and possibly even locally heavy) precipitation to the northern half of the state. Rain will likely also fall in SoCal, though it will probably be lighter in magnitude. By Friday, though, there’s an excellent chance that just about the entire state will have received enough moisture and onshore winds to fully clear the air of smoke, and help to extinguish the remaining flames.

In NorCal, the rains this week should (finally!) be “season-ending” from a wildfire perspective. In the Sierra Nevada, significant snow will fall above pass level–probably giving a boost to early-season snow totals that are currently right around zero. There is some concern that precipitation near the recent burn scars in NorCal (especially the Camp Fire, Carr Fire, and Delta Fire) could be heavy enough to induce debris flows or flooding, especially in areas that have burned very recently in the past two weeks). That will largely depend on how far south a potentially significant atmospheric river event sags next weekend. It’s possible that the heaviest totals will remain up in Oregon or along the far North Coast, but if you do live near or downstream of these fire zones if would be wise to pay attention to the forecasts this week (and, unfortunately, for the winter to come). In SoCal, I don’t think widespread precipitation will be heavy enough to cause major problems in the recent burn scars, but there’s still a slight chance that could change.

All in all, I think this may (understandably!) be one of the most anticipated pattern changes in quite some time. For most, the rain and mountain snow can not come soon enough. In the very long run, there’s still uncertainty whether this pattern change will be sustained or transient; it’s possible that some weak ridging may return to California the week after Thanksgiving. It is also worth noting that there is currently a Red Flag Warning in effect for the Camp Fire zone for the rest of the weekend; gusty winds and dry conditions are once again taking place. This event isn’t too extreme by the standard of recent weeks, but it is worth remembering that until soaking rains arrive later this week, fire risk will remain very high in many places and smoke-related air pollution will remain a major concern. But the key message is this: relief is, finally, on the way.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.