A dry October (with a few exceptions)–but how unusual is that, really?

The first half of autumn has certainly gotten off to a dry start across most of California this year. There have been a couple of local exceptions–patchy regions along the immediate coast of NorCal, where shore-hugging rainbands just made it onshore a few weeks ago, and a broader swath of coastal SoCal, where a widespread and rather spectacular thunderstorm outbreak brought widespread wetting rains earlier this month. But elsewhere, things have been more or less bone dry–and even in places that saw recent precipitation, the dry and relatively warm autumn air has already dried things out considerably. Thus, most of California is running well below average to date in the precipitation department–with no significant rain on the horizon.

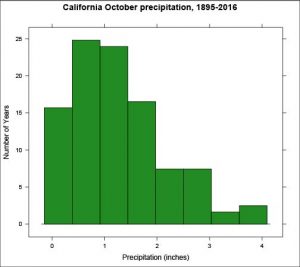

But just how unusual are dry Octobers in California? Well, as I discussed in some depth in a blog post last year: not that unusual. While total precipitation “shut outs” (as will probably occur this year in some places) are decidedly less common, year-to-year variability in October precipitation is very high in California. In most years, October precipitation is quite low across most of the state (especially in the south). What makes October interesting are the occasional but sometimes dramatic exceptions: every 5 years or so, a major October storm event (not infrequently a relic of re-curving typhoons from the West Pacific) will remind us that autumn is a transition season when major California storms are possible (if not likely). More importantly–it’s pretty clear that there is little (if any) meaningful relationship between how much rain California sees in October and how much falls during the core rainy season months in mid-late winter.

Interestingly, a growing body of scientific research suggests that dry autumns in California are becoming more common–a trend that will continue as the climate warms. Our recent research (summarized in a blog post earlier this year) suggests that this trend is now detectable in recent observations–especially in Southern California. It does appear that 2018 will likely end up being another data point that adds to the existing evidence regarding increasingly dry autumns in California.

Fire season is still very much alive in California

Unlike last October (fortunately!), October 2018 has not been a month of extreme wildfire activity in California. The risk has periodically been rather high during dry/windy conditions associated with offshore winds events (which are not uncommon this time of year), but so far the autumn hasn’t added to the devastating wildfire tolls from earlier this summer. Given that little rainfall is expected in the coming days–and that moderate offshore winds, along with warming temperatures, are expected–a renewed wave of wildfire activity could still occur well into November just about anywhere in the state (though climatology would favor the southern half). There are no particularly extreme offshore wind events in the forecast at the moment, but any event that develops prior to the next widespread wetting rains will probably bring a period of renewed extreme fire risk.

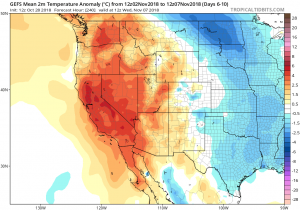

Dry and (increasingly) warm conditions for next 10+ days

Dry (for the most part) and increasingly warm conditions are expected across California over the next 1-2 weeks. This will bring most of the state into the first week of November without any significant rainfall, and model ensembles are suggesting only modest chances for a major pattern change heading toward mid-month. These very dry and warm conditions do start to become progressively more unusual as we head further into November, but are still far from unprecedented.

It’s interesting to note that some fairly densely populated spots along the narrow coastal strip along North Coast and Bay Area could see some of their warmest temperatures of the year in the coming days. Despite extreme heat elsewhere in California for much of the summer, these highly localized “cool spots” stayed under the chilly influence of the marine layer for much of the summer. Now that coastal SSTs have warmed somewhat and periodic dry offshore flow is the rule, these regions will experience much sunnier and warmer conditions than they did for much of the summer. While it’s not unusual for the California coastal strip to see a much later seasonal peak in temperature (in September or October) compared to inland areas (usually July-August), it may be especially noticeable this year given the extreme contrasts experienced earlier this summer.

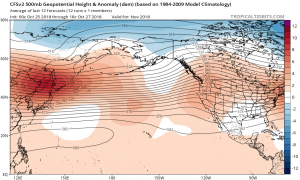

“The Blob” returns to the North Pacific. But what does it mean?

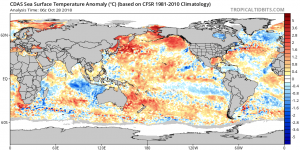

There has been a fair bit of buzz regarding the “return of The Blob”–a region of anomalously warm water in the far northern Pacific (mostly in the Gulf of Alaska). As as been the subject of some of my scientific research (and as I’ve summarized in past blog posts), the consequences for California weather are perhaps different from what a lot of folks might assume. While it’s true that relative ocean warmth in that region and anomalously persistent/strong atmospheric high pressure in the air above “The Blob” do tend to coincide in space and time, what is less clear is the degree to which the warm ocean actually causes high pressure ridging above. In fact, there’s a fair bit of evidence that the causality is reversed–that the persistent atmospheric high pressure develops first, then warms the ocean below due to a lack of storm-generated winds and subsequent upwelling of cooler water from beneath. But there is also some evidence that “The Blob,” once established, may indeed start to influence the longevity of the ridge above–perhaps resulting in a self-reinforcing feedback loop to some degree. If you’re interested in the details, I’d strongly suggest checking out my earlier blog post on this topic.

And what about El Niño? Well, a modest event is still in the forecast–and being depicted by most of the seasonal forecast models. But how much does that factor into California’s winter forecast? In terms of precipitation: probably not much, as the event is not expected to be especially strong or east-focused (a requirement for El Niño to exert a strong influence on California winter precipitation, according to recent research which I summarized back in September). There is, however, a meaningful temperature signal: the developing El Niño does make it likely that winter temperatures across most of the state will be warmer than average (regardless of how much precipitation ultimately falls). Either way, I’ll provide further updates on El Niño’s evolution in the coming months.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.