Where do things stand now?

The last blog post was about another incoming warm, wet Pineapple Express-style atmospheric river storm. That one did indeed end up packing a punch, but that punch landed a fair bit farther to the north than had initially been anticipated. Rain totals were substantial near the Thomas Fire burn area, but rain rates stayed just low enough to avoid major flood and mudslide issues. Further south across much of the urban corridor in SoCal, rainfall ended up being much less than expected due to the more northward track of the storm. Across Central California, though, this storm was extremely impressive; areas from Santa Maria to the southern Sierra Nevada foothills were soaked by prolonged heavy rain that culminated in an extremely intense convective burst as the cold front passed through. This rainfall was so intense that it led to very significant flash flooding near Mariopsa and Groveland near Yosemite National Park and nearly caused the failure of a small dam in the area. Had this rainfall ended up 100-200 miles farther south, as initially anticipated, it could have led to catastrophic flash flooding in the SoCal burn areas. Fortunately, it instead fell in an area that had much greater capacity to absorb the sudden deluge.

How about the Sierra Nevada snowpack? Well, it nearly *tripled* from mid February to late March, yet never reached above about 65% of average at any point this season (and recent record warmth has already triggered melting; the snowpack is already back down to 55% of average for the date). On the other hand, California’s major reservoirs remain nearly capacity and in relatively good shape (still largely due to carryover from last year). Upcoming rains will bolster spring runoff (but probably also melt quite a bit of snowpack; see below). So news is decidedly mixed on the water front, but things do generally look much less dire than they did as recently as a month and a half ago.

Extremely warm “Pineapple Express” headed for NorCal

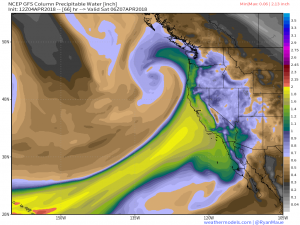

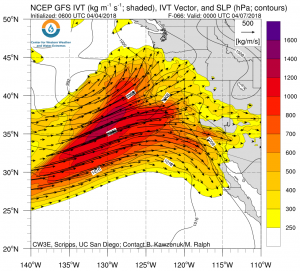

Another extremely warm and moist atmospheric river, with a moisture transport corridor originating near the Hawaiian Islands (hence, “Pineapple Express”), is once again steaming toward California. By several meteorological measures, the airmass associated with this storm is pretty extraordinary: the amount of atmospheric water vapor (precipitable water) expected to be present near San Francisco on Saturday morning may be close to the all-time record value for any time of year. (It’s worth noting that early April is actually the *least* likely time of year for really extreme PW to occur; it’s more likely during the heart of winter (during extreme AR events) or during the late summer months (during our relatively rare “hurricane remnant” events.) This airmass is also expected to be incredibly warm for a California precipitation event; freezing levels could be as high as 10,000 feet or even higher during the initial part of the storm, with rain (instead of snow) expected at even very high mountain locations. Daytime temperatures during cloudy and rainy conditions on Fri/Sat will be in the 60s, and could even approach 70 in some spots (so things will feel very muggy and subtropical indeed).

Whoa: amount of atmospheric moisture near Bay Area could approach *all time* record high level on Sat w/incoming #PineappleExpress #AtmosphericRiver at exact time of year when it typically reaches *minimum* value. That's incredible! #CAwx #CAwater h/t @NWSBayArea pic.twitter.com/M3z6Xts2tD

— Dr. Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) April 3, 2018

Given the “record atmospheric moisture” statistics cited above, why isn’t there more concern over an extremely dangerous or damaging storm? Well, as has been previously noted: atmospheric moisture isn’t everything that matters when it comes to producing an epic deluge. In order to “squeeze out” all of that water vapor as precipitation, there has to be some atmospheric mechanism to cause air to rise, water to condense, and precipitation to subsequently fall. During the initial portion of this AR event, there will be almost no dynamic atmospheric lifting mechanism–the coastal mountains themselves will have to do all the heavy lifting. As a result, the initial precipitation will be very strongly orographic in nature–persistent and locally heavy on south and west facing slopes, but very light and intermittent everywhere else. As Saturday approaches and a modest cold front begins to move across California, more “dynamic” lift will come into play and precipitation will become at least briefly heavy across all of NorCal. At the very tail end of the event, colder air aloft will move in, destabilizing the atmosphere over interior NorCal and perhaps resulting in a line of two of extremely heavy convective downpours enhanced by the existing subtropical moisture (not unlike what happened during the last event in the Sierra Nevada foothills). It’s during that last burst when the risk of localized flash flooding and mudslides will be highest.

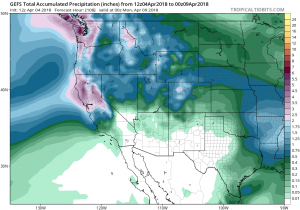

A very impressive April rainfall event, but will probably bring net snowpack loss

To be clear: this will be an extremely impressive, and probably record-breaking April rainfall event for many parts of NorCal. But the main reason for this is that April tends not to be a big rainfall month, so record precipitation values are much lower than for (say) January or February. In other words: this would be a very respectable rainfall event at any time of year, but it’s especially anomalous this late in the rainfall season. The corollary, though, is that this is not the “mega storm” that a few media outlets have made it out to be. It will feel like a significant mid-winter storm, but it will be of a magnitude that we’ve seen several times in the past couple of years. There could be some significant localized flooding issues if the atmospheric river stalls out over a specific watershed (most likely somewhere near the Santa Cruz Mountains or southern Sierra Nevada foothills), but most rivers and streams are running relatively low at the moment so there will be reasonable capacity to absorb the water. It’s worth noting, though, that with record atmospheric moisture comes at least a slight possibility that the models may be underestimating the precipitation potential with this storm, so it would be wise to keep a close eye on the forecast as it evolves over the next 3 days.

More widespread flooding, though, is definitely possible in the Sierra Nevada and along the western foothills, where this storm will produce rain (instead of snow) at virtually all elevations. Rapid runoff is expected in rivers like the Truckee and Merced, both of which will likely exceed flood stage this weekend (possibly resulting in significant flooding in Yosemite National Park). Most of this will be the result of several inches of rainfall, but significant rain-on-snow snowmelt will occur at lower elevations where the existing snowpack is already pretty thin and warm/isothermal (i.e., right at freezing throughout the snow column and therefore susceptible to melt). At higher elevations where the snowpack is deeper, it’s a bit uncertain just how much snow the rain will melt. It takes a counterintuitively large amount of energy to melt snow, and colder snowpacks have significant capacity to absorb water. Still, it’s quite likely that that the snowpack will actually be *smaller* after this storm moves through than it was before–meaning that this Pineapple Express will likely be a net snow melter.

More widespread flooding, though, is definitely possible in the Sierra Nevada and along the western foothills, where this storm will produce rain (instead of snow) at virtually all elevations. Rapid runoff is expected in rivers like the Truckee and Merced, both of which will likely exceed flood stage this weekend (possibly resulting in significant flooding in Yosemite National Park). Most of this will be the result of several inches of rainfall, but significant rain-on-snow snowmelt will occur at lower elevations where the existing snowpack is already pretty thin and warm/isothermal (i.e., right at freezing throughout the snow column and therefore susceptible to melt). At higher elevations where the snowpack is deeper, it’s a bit uncertain just how much snow the rain will melt. It takes a counterintuitively large amount of energy to melt snow, and colder snowpacks have significant capacity to absorb water. Still, it’s quite likely that that the snowpack will actually be *smaller* after this storm moves through than it was before–meaning that this Pineapple Express will likely be a net snow melter.

All in all: this will certainly be an interesting storm to watch, and there is the possibility that flood issues could arise in some places in NorCal. But the good news is that the SoCal burn areas (including the Thomas Fire) probably have little to worry about with this one; unless the forecast changes drastically, only very light rainfall is expected from Santa Barbara southward. (It would have been nice, actually, if this one was aimed a bit closer to Los Angeles, since most of SoCal is still far below average precipitation-wise for the season to date).

A programming note: my colleagues and I have just completed a new study on changing California precipitation extremes, and the associated paper will be released in late April. I’ll be writing a special Weather West article discussing this work, as well as other related studies. Stay tuned for this post around April 23!

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.