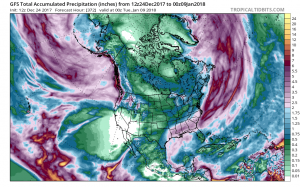

Bone dry in Southern California, and below average precip throughout CA

It has been an extraordinarily dry autumn and early winter across Southern California. Northern California had been faring better in the precipitation department so far this season, with near-average autumn rains in most areas. But in recent weeks, Southern California’s dryness has begun to expand northward along the Pacific Coast–now encompassing all of California, and even beginning to creep north of the state line into parts of the Pacific Northwest.

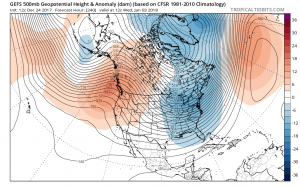

Why has California been so dry? (Regular blog visitors already know where I’m going with this.) Well, a remarkably persistent zone of atmospheric pressure has been present more often than not across the region for the past few months. Early in the season, this ridge was centered across Southern California and the interior Southwest–but recently, a broader “full-latitude” ridge feature has expanded to encompass much of the West Coast. This temporal evolution is the reason for the SoCal/NorCal precip split early in the season. A couple of months ago, Pacific storms had been redirected only slightly to the north of the SoCal metro areas due to subtropical ridging (into the Bay Area and points northward). More recently, the bigger & stronger West Coast ridge has pushed the Pacific storm track even further north. Remarkably, this powerful ridge has forced several very moist atmospheric river storms over the mid-Pacific to make a hard “left turn” over the open ocean–veering directly northward and bringing almost inconceivably heavy snowfall to the coastal mountains of southern Alaska.

Thomas Fire becomes largest wildfire in modern California history–in December

One conspicuous and locally devastating consequence of the delayed rainy 2017 rainy season in Southern California is the extension of wildfire season well into winter. While December wildfires are not unheard of in this part of the world, the extent and severity of the December 2017 fires in SoCal really is unprecedented in California history. The Thomas Fire–which has now burned nearly 275,000 acres and over a thousand structures in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties–yesterday became the single largest wildfire in modern California history. That this dubious milestone was reached in December, which is typically the midst of the California rainy season, is truly extraordinary. Indeed, recent months have brought not only near-record low precipitation, but also record-high temperatures across a wide swath of SoCal.

This long-term warmth and dryness set the stage for an unusually prolonged stretch of land-to-sea Santa Ana winds in recent days to push recent fires far further and faster than would usually be possible this time of year. An amazing indicator of how anomalous this winter airmass was: on several occasions over the past 2 weeks, relative humidities near the beaches of Southern California fell as low as 1%–with surface dewpoints at or below -20F in some nearby spots, and column water vapor under 0.1 inch. In other words: there was essentially no moisture at all in the airmass that has lingered over SoCal for many days. While long-term humidity records are hard to come by in most spots, all signs suggest that these were at or near record-low humidity values for many of these recording stations (and certainly for the time of year).

Is this (another) return of the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge?

This is a question that I’ve been hearing increasingly often in recent days. “The Triple R” certainly has anxiety-inducing connotations for many Californians who endured record-breaking drought just a few years ago. (This is something to which I can personally attest: I live in Los Angeles at the moment, and I personally haven’t witnessed any precipitation other than brief drizzle since late March). And its return would rightfully raise some eyebrows, given recent research suggesting that such pressure patterns have indeed been occurring more frequently in recent years.

My current answer: we’re not in Triple R territory quite yet, but we’re getting close. We have certainly witnessed the return of resilient ridging near California, but I don’t think we’ve yet reached the “ridiculous” level of multi-month persistence that occurred during the height of the recent California drought. Should present conditions persist through January, and if seasonal precipitation has not started to recover from its early deficit by that time, I may have to revise that answer.

The good news: wet conditions last winter did help to top up reservoirs in the northern part of the state–meaning that the state’s overall water supply situation looks okay even if very dry conditions persist for the rest of winter. Last winter’s lowland flooding did help to modestly recharge shallow groundwater aquifers in the north, which has (temporarily) stemmed the long-term loss of capacity in these regions.

The not-so-good news: parts of Southern California that depend exclusively on local water supplies (such as much of Santa Barbara and Ventura counties) never really recovered from the last drought, and these regions remain quite susceptible to the impacts of drought re-intensification. And even further north, forested regions remain quite stressed as a result from the previous multi-year drought, and tree mortality in the Sierra Nevada remains far above historically observed levels.

Unfortunately, 2+ weeks of unusually dry conditions still probable

I wish I had better news regarding the forecast, but at there moment there’s still no real sign of rain returning to California in the coming days. Occasional light precipitation is possible across the north, but conditions will likely be nearly/totally dry across the southern half of the state for the foreseeable future. There has been–and remains–strong, multi-model agreement that West Coast ridging will persist for at least 1-2 more weeks. It has been remarkable to see day after day of numerical model forecasts depicting near-zero 16-day precipitation accumulations during what is normally the heart of the rainy season, and today’s runs (unfortunately) are no exception. The “Warm West/Cool East” pattern discussed in the previous post is still quite prominent over North America. The present West Coast dryness is largely consistent with seasonal model predictions for this winter, and those same models presently suggest that the present pattern is likely to persist for much of the California rainy season.

All of this is to say: it’s still too early to say whether we’re headed into a new drought, though there are some compelling signs that we may be (especially in Southern California). And even in a dry year, California can still experience big storms and very wet months. But at this point, it probably makes sense to start thinking about the possibility of yet another big swing in California–from drought, to flood, and then (perhaps) back again.

Discover more from Weather West

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.